-AUGUST 8, 2020 11:40 PM

2nd of three parts

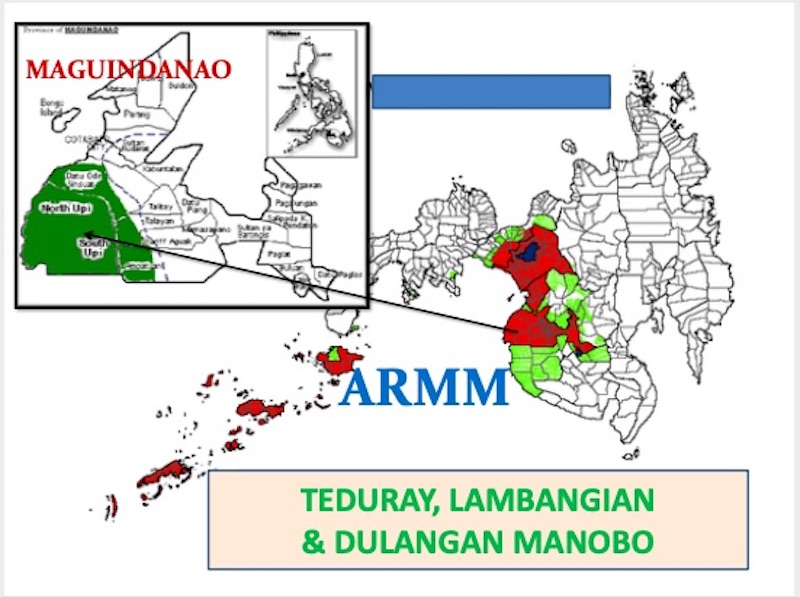

DAVAO CITY (MindaNews / 08 August) — The Tedurays, Lambangians and Dulangans in Maguindanao and other non-Moro IPs in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) became part of the Bangsamoro region in the past four decades, since the first autonomous government was set up in 1979 as the Regional Autonomous Regions (RAGs) in Central and Western Mindanao under then President Ferdinand Marcos.

The RAGs were abolished with the establishment of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) in 1990 under President Corazon Aquino, until it was abolished in favor of the BARMM in February 2019 under President Rodrigo Duterte.

Santos Unsad, Assistant Supreme Tribal Chief of the Timuay Justice and Governance (TJG), estimates their population in Maguindanao at 128,000.

The Philippine Statistics Authority estimates the BARMM population as of 2015 at 3.8 million.

Courtesy of TLWOI

Froilyn Mendoza, Executive Director of the Teduray Lambangian Women’s Organization Inc., said the total IP ancestral domain claim in Maguindanao and Lanao del Sur is 309,720 hectares perimeter area, comprising of 215,941 hectares of land and 93,779 coastal waters.

Before the mass evacuations in South Upi this year, a “cyclical pattern of conflict and displacement” has been noted since 1996 within the IP areas in what is now the BARMM, according to a presentation of the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) Philippines, during an online forum on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the BARMM on July 29, initiated by the Non-Violent Peace Force in partnership with the Ministry of Indigenous People’s Affairs and Ministry of Social Services and Development.

Elson Monato, Mindanao Protection Officer of UNHCR-Philippines cited several incidents: forcible eviction of IPs from Mt. Firis in the mountains of Daguma Range in 1996 when an armed group established a camp; displacement of IPs in Datu Saudi Ampatuan, Datu Unsay and Datu Hofer towns in Maguindanao in the 2008 war; displacement of IPs in Hill 224 in 2010 and 2011 due to continuous harassment of armed groups, prompting IPs to join the paramilitary CAFGU; in December 2012 and October 2015, when approximately 200 IPs were forcibly displaced due to alleged harassment of armed group, due to land dispute in San Jose, South; armed conflict in Bajar, Pandan, also due to land dispute in 2013 and 2014; in February 2016, 21 IP Teduray families from Sitio Megelaway, Barangay Kuya, South Upi, fled their homes because of alleged threats from an armed group; in July 2019 in Barangay Kuya, residents of Sitios Walew, Ideng, Furo Wagey and Dakeluan fled due to alleged harassment of armed group over land.

Mendoza, in several presentations, goes back to the 1970s, where more than 10,000 Teduray families from four barangays in the Firis Complex, she said, fled due to armed conflict between the Blackshirts and the Ilaga.

Marcos declared martial law in September 1972, engaged in peace negotiations with the Moro National Liberation Front in 1976 but he set up two RAGs instead of just one autonomous region, eventually leading to the collapse of the peace process. Soonafter, the MNLF broke into factions with MNLF Vice Chair Salamat Hashing forming the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and Dimas Pundato, the MNLF Reformist Group.

According to Mendoza, the “armed group” that set up camp there in Firis in 1996, was the MILF which claimed it as their “satellite camp” in their peace negotiations with the government.

The Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), which broke away from the MILF in 2010, also set up camp in the area when it was organized by Ustadz Amiril Umra Kato, who resigned as commander of the 105th Base Command of the MILF’s Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces (BIAF) over policy differences with the MILF leadership.

Aside from encroachment by the armed groups, a policy brief of the Institute of Autonomy and Governance (IAG) in May 2011 showed that between 2002 and 2006, the ARMM’s Regional Legislative Assembly (RLA) passed laws creating new municipalities “carved out from Teduray ancestral homelands, such as the Mt. Firis sacred mountain complex into the municipalities of Datu Unsay, Datu Saudi, Guindulugan, Sharif Aguak, and Talayan which were inevitably ruled by Maguindanaon Mayors.”

It added that regional laws also “removed 12 coastal barangays of Upi to form the Datu Blah Sinsuat municipality, and renamed the Teduray ancestral domain portions of Dinaig town into the Datu Odin Sinsuat municipality.”

Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997

When the IPRA was passed in 1997, it gave hope to IPs nationwide and was even referred to as the government’s ”peace agreement” with the IPs. The law recognizes the four bundles of IP rights: ancestral domains and lands; self governance and empowerment; social justice and human rights; and cultural integrity.

Within the ARMM, IPRA initially gave hope to the IPs but the ARMM bowed out of office on February 26, 2019 with IPRA not implemented in the region.

RA 6734 which created the ARMM was ratified in 1989 while its amended version, RA 9054 was ratified in 2001.

Froilyn Mendoza, Executive Director of the Teduray Lambangian Women’s Organization Inc., said the total IP ancestral domain claim in Maguindanao and Lanao del Sur is 309,720 hectares perimeter area, comprising of 215,941 hectares of land and 93,779 coastal waters.

Before the mass evacuations in South Upi this year, a “cyclical pattern of conflict and displacement” has been noted since 1996 within the IP areas in what is now the BARMM, according to a presentation of the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) Philippines, during an online forum on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the BARMM on July 29, initiated by the Non-Violent Peace Force in partnership with the Ministry of Indigenous People’s Affairs and Ministry of Social Services and Development.

Elson Monato, Mindanao Protection Officer of UNHCR-Philippines cited several incidents: forcible eviction of IPs from Mt. Firis in the mountains of Daguma Range in 1996 when an armed group established a camp; displacement of IPs in Datu Saudi Ampatuan, Datu Unsay and Datu Hofer towns in Maguindanao in the 2008 war; displacement of IPs in Hill 224 in 2010 and 2011 due to continuous harassment of armed groups, prompting IPs to join the paramilitary CAFGU; in December 2012 and October 2015, when approximately 200 IPs were forcibly displaced due to alleged harassment of armed group, due to land dispute in San Jose, South; armed conflict in Bajar, Pandan, also due to land dispute in 2013 and 2014; in February 2016, 21 IP Teduray families from Sitio Megelaway, Barangay Kuya, South Upi, fled their homes because of alleged threats from an armed group; in July 2019 in Barangay Kuya, residents of Sitios Walew, Ideng, Furo Wagey and Dakeluan fled due to alleged harassment of armed group over land.

Mendoza, in several presentations, goes back to the 1970s, where more than 10,000 Teduray families from four barangays in the Firis Complex, she said, fled due to armed conflict between the Blackshirts and the Ilaga.

Marcos declared martial law in September 1972, engaged in peace negotiations with the Moro National Liberation Front in 1976 but he set up two RAGs instead of just one autonomous region, eventually leading to the collapse of the peace process. Soonafter, the MNLF broke into factions with MNLF Vice Chair Salamat Hashing forming the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and Dimas Pundato, the MNLF Reformist Group.

According to Mendoza, the “armed group” that set up camp there in Firis in 1996, was the MILF which claimed it as their “satellite camp” in their peace negotiations with the government.

The Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), which broke away from the MILF in 2010, also set up camp in the area when it was organized by Ustadz Amiril Umra Kato, who resigned as commander of the 105th Base Command of the MILF’s Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces (BIAF) over policy differences with the MILF leadership.

Aside from encroachment by the armed groups, a policy brief of the Institute of Autonomy and Governance (IAG) in May 2011 showed that between 2002 and 2006, the ARMM’s Regional Legislative Assembly (RLA) passed laws creating new municipalities “carved out from Teduray ancestral homelands, such as the Mt. Firis sacred mountain complex into the municipalities of Datu Unsay, Datu Saudi, Guindulugan, Sharif Aguak, and Talayan which were inevitably ruled by Maguindanaon Mayors.”

It added that regional laws also “removed 12 coastal barangays of Upi to form the Datu Blah Sinsuat municipality, and renamed the Teduray ancestral domain portions of Dinaig town into the Datu Odin Sinsuat municipality.”

Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997

When the IPRA was passed in 1997, it gave hope to IPs nationwide and was even referred to as the government’s ”peace agreement” with the IPs. The law recognizes the four bundles of IP rights: ancestral domains and lands; self governance and empowerment; social justice and human rights; and cultural integrity.

Within the ARMM, IPRA initially gave hope to the IPs but the ARMM bowed out of office on February 26, 2019 with IPRA not implemented in the region.

RA 6734 which created the ARMM was ratified in 1989 while its amended version, RA 9054 was ratified in 2001.

Leaders of Indigenous Peoples in the Bangsamoro core territory air their concerns at the Mindanao Indigenous Peoples’ Legislative Assembly (MIPLA) on August 29, 2017 in Davao City. Screen grabbed from OPAPP video

Non-Moro IPs exerted efforts to work for the devolution of powers of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) to the ARMM Government.

Initiatives were also made to get an Executive Order (EO) from Presidents Joseph Estrada (1998-2001) and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (2001 to 2010) but none was issued.

There was no EO either under President Aquino (2010 to 2016) but ARMM Governor Mujiv Hataman and NCIP chair Leonor Oralde-Quintayo settled for the signing of a Memorandum of Agreement for the implementation of the provisions of IPRA especially those related to the ancestral domain delineation as part of a confidence building measure for affected IPs in the then ongoing peace negotiations between government and the MILF.

The IP leaders convened a Tribal Congress on October 25, 2013 at the municipal gym in Nuro, Upi, Maguindanao and a unanimous decision was reached to pursue the ancestral domain delineation in ARMM.

But no signing ever happened. The ARMM’s Office of the Attorney General in a September 13, 2013 opinion, explained that while the Governor is authorized under the law to enter into MOUs and can undertake measures to protect the ancestral domain and ancestral lands of the IPs, the coverage of the MOU in matters of processing the formal recognition of ancestral domains is only in Maguindanao. “It is not clear as to whether the other four provinces in the ARMM are included in the MOU,” hence the coverage “must be clarified and specified.”

In a statement at the end of the Limud Baglalan Témanding Kuwagib Bé Fusaka Ingéd (Tribal Leaders’ Conference to Re-examine IP Rights on Ancestral Domains) on December 13 to 15, 2013) in Datu Odin Sinsuat, Maguindanao, the leaders noted that in the past 16 years since IPRA was passed, it had yet to be implemented in the ARMM.

“Burying” IPRA

The leaders said that a week earlier, on December 8, they received a “shocking news” that government and the MILF signed an Annex on Power-Sharing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and “we were surprised that all provisions for the IP agenda in the peace process were devolved entirely by the GPH (Government of the Philippines) to the ‘exclusive power’ of the Bangsamoro without consideration to our positions submitted to the GPH and MILF since 2005, and to the present through the Bangsamoro Transition Commission.”

“What happened to the Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) provisions of IPRA and the UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples)?

Non-Moro IPs exerted efforts to work for the devolution of powers of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) to the ARMM Government.

Initiatives were also made to get an Executive Order (EO) from Presidents Joseph Estrada (1998-2001) and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (2001 to 2010) but none was issued.

There was no EO either under President Aquino (2010 to 2016) but ARMM Governor Mujiv Hataman and NCIP chair Leonor Oralde-Quintayo settled for the signing of a Memorandum of Agreement for the implementation of the provisions of IPRA especially those related to the ancestral domain delineation as part of a confidence building measure for affected IPs in the then ongoing peace negotiations between government and the MILF.

The IP leaders convened a Tribal Congress on October 25, 2013 at the municipal gym in Nuro, Upi, Maguindanao and a unanimous decision was reached to pursue the ancestral domain delineation in ARMM.

But no signing ever happened. The ARMM’s Office of the Attorney General in a September 13, 2013 opinion, explained that while the Governor is authorized under the law to enter into MOUs and can undertake measures to protect the ancestral domain and ancestral lands of the IPs, the coverage of the MOU in matters of processing the formal recognition of ancestral domains is only in Maguindanao. “It is not clear as to whether the other four provinces in the ARMM are included in the MOU,” hence the coverage “must be clarified and specified.”

In a statement at the end of the Limud Baglalan Témanding Kuwagib Bé Fusaka Ingéd (Tribal Leaders’ Conference to Re-examine IP Rights on Ancestral Domains) on December 13 to 15, 2013) in Datu Odin Sinsuat, Maguindanao, the leaders noted that in the past 16 years since IPRA was passed, it had yet to be implemented in the ARMM.

“Burying” IPRA

The leaders said that a week earlier, on December 8, they received a “shocking news” that government and the MILF signed an Annex on Power-Sharing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and “we were surprised that all provisions for the IP agenda in the peace process were devolved entirely by the GPH (Government of the Philippines) to the ‘exclusive power’ of the Bangsamoro without consideration to our positions submitted to the GPH and MILF since 2005, and to the present through the Bangsamoro Transition Commission.”

“What happened to the Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) provisions of IPRA and the UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples)?

On December 9, the leaders agreed to meet on December 13 to 15, emphasizing that the IPs in the ARMM “loved IPRA; we did not surrender our rights under IPRA until its last breath.”

“Now, we will bury IPRA in a sacred place within our domain so that we and our children cannot accidentally step upon and violate the law. But we assured other TPs (Tribal Peoples) and IPs that we bring with us the spirit of IPRA in the next battle” on the formulation of laws for the IPs in the BBL “to give the four bundles of rights in IPRA a new life.”

The leaders stressed that they want a “just BBL, a just Bangsamoro Government and a just Bangsamoro society and that no group will be oppressed, discriminated and their rights be trampled upon, in order to have a genuine and lasting peace in Mindanao.”

Timuay Alim Bandara, Council Member of the Teduray Justice aand Governance, head claimant of their ancestral domain claim filed in 2005. Photo from his FB page posted by Jenny Catuyan

Timuay Alim Bandara, TJG Council member, told MindaNews that the “burial” was called off because the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process appealed to then South Upi Mayor Jovito Martin to appeal to the leaders not to push through with the plan.

Bandara explained that at that time in 2013, “may hindi malinaw doon sa terminong exclusive power lalo na that time talagang ayaw ng MILF ang IPRA” (the term exclusive power was not clear, especially at that time when the MILF was really against IPRA).

Attempts to implement IPRA

But Bandara said there were several attempts in the ARMM to implement IPRA.

According to the May 2011 IAG policy brief, the ARMM’s RLA passed Resolution 269 on August 15, 2003, under the Hussein administration, approving IPRA as “the legal framework to recognize” the rights of the IPs.

On October 30, 2003, the ARMM and NCIP signed a Memorandum of Understanding recognizing the partnership of the two agencies to set up the mechanism to ensure the application of IPRA in ARMM while the ARMM’s RLA formulates its own IPRA.

To immediately address the concerns of IPs within ARMM, the NCIP and ARMM agreed to establish the mechanisms through the Office of Southern Cultural Communities (OSCC) in the ARMM, closely working with NCIP.

In 2004, the NCIP en banc issued Resolution 24 endorsing to then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo the joint technical working group draft executive order creating the NCIP-ARMM.

In 2005, the NCIP en banc issued Resolution 119, approving the implementation of RLA Resolution 269 for delineation of ancestral domain/ancestral land claims of non-Moro IPs in the ARMM.

On May 26, 2008, under the Ampatuan administration, the RLA passed Muslim Mindanao Act 241 or the Tribal Peoples Rights Act to “recognize, respect, protect and promote the Rights, Governance and Justice Systems, and customary laws of the Indigenous Peoples/Tribal Peoples of the ARMM.” It reaffirmed the policies and principles enshrined in the IPRA and international law.

But Development Anthropologist Elena Joaquin Damaso, author of the May 2001 IAG policy brief, said, the ARMM law “did not contain tacit provisions for the delineation and titling of ancestral domains” and did not also mandate the creation of an NCIP-ARMM or the transformation of the OSCC as the implementer of MMA 241 and other right-based policies.

In 2012, under the Hataman administration, the rules and regulations implementing the local law was passed.

According to the opinion of the Legal Affairs Office for the NCIP en banc on January 10, 2013, one of the highlights of the IRR were provisions on the issuance of Certificates of Ancestral Domain Titles (CADTs) and Certificates of Ancestral Land Titles CALTs).

It also provides under Rule IX, Section 1 that until the NCIP-ARMM is organized, the OSCC shall accept applications for CADT and CALT “as the authorized agent of the NCIP.” After accepting the application, the application will be forwarded to the NCIP for processing.

Resolution 38

But even as the Bangsamoro law already guarantees the IPs their rights under IPRA, the IPs in the BARMM last year suffered a major setback: just as they were about to complete the process for delineation of their ancestral domain and the issuance of their CADT, the BTA Parliament passed Resolution No. 38 on September 25, 2019 to protest the delineation process in Maguindanao. It also urged the NCIP to “cease and desist” from proceeding with the delineation process and issuance of CADT.

Citing RA 11054, the resolution said the MIPA “has exclusive power and authority over Indigenous Peoples’ rights and affairs including their ancestral domain in the BARMM.”

The NCIP, it stressed, “has no power and authority to conduct delineation process and issue CADT in the BARMM.”

Ulama explained that Resolution 38 was issued because NCIP in neighboring Region 12 (Soccsksargen) was “trespassing.”

He claimed the NCIP did not ask permission from barangay and municipal officials and that the IP’s right to FPIC was also violated.

But who asked for the delineation? Ulama said “mga Teduray gihapon” (fellow Tedurays).

Bandara dismissed Ulama’s allegation of “trespassing” and lack of FPIC.

He said the process of delineation started in 2005. (Carolyn O. Arguillas / MindaNews)

Timuay Alim Bandara, TJG Council member, told MindaNews that the “burial” was called off because the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process appealed to then South Upi Mayor Jovito Martin to appeal to the leaders not to push through with the plan.

Bandara explained that at that time in 2013, “may hindi malinaw doon sa terminong exclusive power lalo na that time talagang ayaw ng MILF ang IPRA” (the term exclusive power was not clear, especially at that time when the MILF was really against IPRA).

Attempts to implement IPRA

But Bandara said there were several attempts in the ARMM to implement IPRA.

According to the May 2011 IAG policy brief, the ARMM’s RLA passed Resolution 269 on August 15, 2003, under the Hussein administration, approving IPRA as “the legal framework to recognize” the rights of the IPs.

On October 30, 2003, the ARMM and NCIP signed a Memorandum of Understanding recognizing the partnership of the two agencies to set up the mechanism to ensure the application of IPRA in ARMM while the ARMM’s RLA formulates its own IPRA.

To immediately address the concerns of IPs within ARMM, the NCIP and ARMM agreed to establish the mechanisms through the Office of Southern Cultural Communities (OSCC) in the ARMM, closely working with NCIP.

In 2004, the NCIP en banc issued Resolution 24 endorsing to then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo the joint technical working group draft executive order creating the NCIP-ARMM.

In 2005, the NCIP en banc issued Resolution 119, approving the implementation of RLA Resolution 269 for delineation of ancestral domain/ancestral land claims of non-Moro IPs in the ARMM.

On May 26, 2008, under the Ampatuan administration, the RLA passed Muslim Mindanao Act 241 or the Tribal Peoples Rights Act to “recognize, respect, protect and promote the Rights, Governance and Justice Systems, and customary laws of the Indigenous Peoples/Tribal Peoples of the ARMM.” It reaffirmed the policies and principles enshrined in the IPRA and international law.

But Development Anthropologist Elena Joaquin Damaso, author of the May 2001 IAG policy brief, said, the ARMM law “did not contain tacit provisions for the delineation and titling of ancestral domains” and did not also mandate the creation of an NCIP-ARMM or the transformation of the OSCC as the implementer of MMA 241 and other right-based policies.

In 2012, under the Hataman administration, the rules and regulations implementing the local law was passed.

According to the opinion of the Legal Affairs Office for the NCIP en banc on January 10, 2013, one of the highlights of the IRR were provisions on the issuance of Certificates of Ancestral Domain Titles (CADTs) and Certificates of Ancestral Land Titles CALTs).

It also provides under Rule IX, Section 1 that until the NCIP-ARMM is organized, the OSCC shall accept applications for CADT and CALT “as the authorized agent of the NCIP.” After accepting the application, the application will be forwarded to the NCIP for processing.

Resolution 38

But even as the Bangsamoro law already guarantees the IPs their rights under IPRA, the IPs in the BARMM last year suffered a major setback: just as they were about to complete the process for delineation of their ancestral domain and the issuance of their CADT, the BTA Parliament passed Resolution No. 38 on September 25, 2019 to protest the delineation process in Maguindanao. It also urged the NCIP to “cease and desist” from proceeding with the delineation process and issuance of CADT.

Citing RA 11054, the resolution said the MIPA “has exclusive power and authority over Indigenous Peoples’ rights and affairs including their ancestral domain in the BARMM.”

The NCIP, it stressed, “has no power and authority to conduct delineation process and issue CADT in the BARMM.”

Ulama explained that Resolution 38 was issued because NCIP in neighboring Region 12 (Soccsksargen) was “trespassing.”

He claimed the NCIP did not ask permission from barangay and municipal officials and that the IP’s right to FPIC was also violated.

But who asked for the delineation? Ulama said “mga Teduray gihapon” (fellow Tedurays).

Bandara dismissed Ulama’s allegation of “trespassing” and lack of FPIC.

He said the process of delineation started in 2005. (Carolyn O. Arguillas / MindaNews)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.