From the New Straits Times (Apr 8 2019):

Malaysians, and the world, have forgotten about Marawi. Here's a reminder

MARAWI, Philippines: Mara-where? Many must prod their brains to recall an apocalyptic 5-month-long conflict in 2017 in the centre of a flourishing Asian city – which was consequently wiped off the map.

International news outlets gave due “if it bleeds, it leads” coverage to the stupefying, out-of-left-field siege of Marawi, the Philippines as it unfolded – but predictably withdrew from the scene after the last shot was fired, the last bomb detonated.

The surreal, 21st Century urban strife rapidly faded from memory – even those of Malaysians, living snugly, just a bomb’s-throw away.

But although almost two years have passed since the WAR officially ended, the BATTLE to survive among Marawi’s dispossessed and distressed residents and refugees – who are legion – grinds on.

Their plight has not been entirely forgotten, however, as among those without convenient amnesia over the cataclysm is the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which is gingerly and steadfastly guiding the people of Marawi towards a semblance of recovery.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

No man’s land

The capital city of Lanao del Sur province, in the west of Mindanao island, Marawi and its environs – which are slung along the northern coast of postcard-pretty Lake Lanao – are today a patchwork of zones of varying degrees of ruin, loss, chaos and deprivation.

At its stilled heart is the downtown area – a four-square-kilometre No Man’s Land so utterly ravaged it is colloquially referred to as “Ground Zero”, and officially, as the Most Affected Area (MAA). It is a textbook post-Armageddon urban setting of block after block of hollowed-out, shrapnel-pitted multi-storey buildings (somehow defying gravity) and mounds or mountains of rubble. The cracked walls of many wobbly, still-standing structures are peculiarly accessorised with two types of graffiti – the first, authored by cheeky Islamic militants at the height of clashes, read: “City of IS (Islamic State)” and “We Love Maute” (a reference to terrorist brothers who were among the architects of the siege); and the second, hastily penned by fleeing home and business owners to indicate proprietorship, read: “This property belongs to ____”. Most strikingly, luxuriant tropical vegetation – in the form of weeds and climbing vines – have crept forward and partly consumed many structures left abandoned for 23 months, as if nature is quietly reclaiming its long-lost territory.

According to the ICRC, an astonishing 95 per cent, or 6,800 buildings in the MAA were partially destroyed or reduced to dust.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

The MAA can be said to be “MIA” post-siege, as it remains completely off-limits to both former residents and construction machinery for one reason – it is littered with unexploded ordnances (UXOs). Site of the final and most ferocious battles between retreating Islamic extremist fighters and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), the MAA teems with undetonated Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) planted by the militants; and 500-pound bombs dropped by AFP warplanes during surgical airstrikes. Among the latter are Deep-buried Bombs which cleverly dug themselves into the soil beneath the rubble, and the exact locations of which are difficult to pinpoint. The MAA’s UXO orchard is ripe for catastrophic explosions, as the ordnances can be triggered by anything from heavy rain to minor earthquakes (common in the tectonically-active Philippines). According to the ICRC, detecting, defusing and removing the devices is an extremely complex, expensive and time-consuming process – but the government agency set up to oversee the rehabilitation of the MAA, Task Force Bangon Marawi, declared that UXO-clearing can be completed by 2021 (an overly-optimistic estimation, according to some).

Also standing in the way of instant rebuilding is the presence of an unknown number of human remains amidst the rubble – the uncovering, recovery and identification of which is also a difficult and lengthy process, tirelessly led by the ICRC’s Department of Protection. Step by tentative step, the ICRC has and continues to collect human tissue samples, conduct DNA testing and compile lists of missing persons from devastated families unsure of the fate of their kin – whether civilian, soldier or Islamic insurgent.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

Stillbirth?

In contrast to the black hole of the MAA, signs of re-introduced life just outside its army checkpoint-dotted border are impossible to ignore. Across the city’s main Agus River, in Marawi’s less-severely decimated north-western district, human activity is practically feverish. Damaged and destroyed property abound – but so too are demolition and construction efforts (most, without the aid of much heavy machinery). Many still-standing buildings of questionable structural integrity have been crudely transformed into makeshift or permanent homes; while new, wooden and bamboo roadside stalls selling sundry everyday goods have sprouted richly. Meanwhile, cars, jeeps and tricycles (run-of-the-mill ‘kapchais’ cleverly-fitted with sidecars) tear down the dust-covered concrete and dirt roads as if driven by daredevils. Water supply, though not potable, and electricity, though spotty, have been largely restored outside the MAA – and the 64,000 people who were allowed to return to their abodes (or the remains of them) are making a go at rebuilding their lives.

Despite returning home with hopes of a renaissance, life for formerly-displaced Marawi residents, the majority of whom are ethnic-Maranao Muslims, is an exercise in extreme hardship. Most permanently parted with all their money and property, livelihoods and multiple family members – and are at a loss as to how to restart their shattered lives. Meanwhile, the trauma of having lived through the barbarity of civil war and being utterly dispossessed and disenfranchised for months has left paralysing psychological scars for entire communities unsure of what the future holds. And although martial law, declared for all of Mindanao during the siege, is still in force – ensuring the imposition of a curfew and the omnipresence of army personnel across Marawi – some Maranao fear a re-eruption of activity by Muslim rebels who survived the war and retreated to their shrouded strongholds, island-wide.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

Nowhere, with nothing

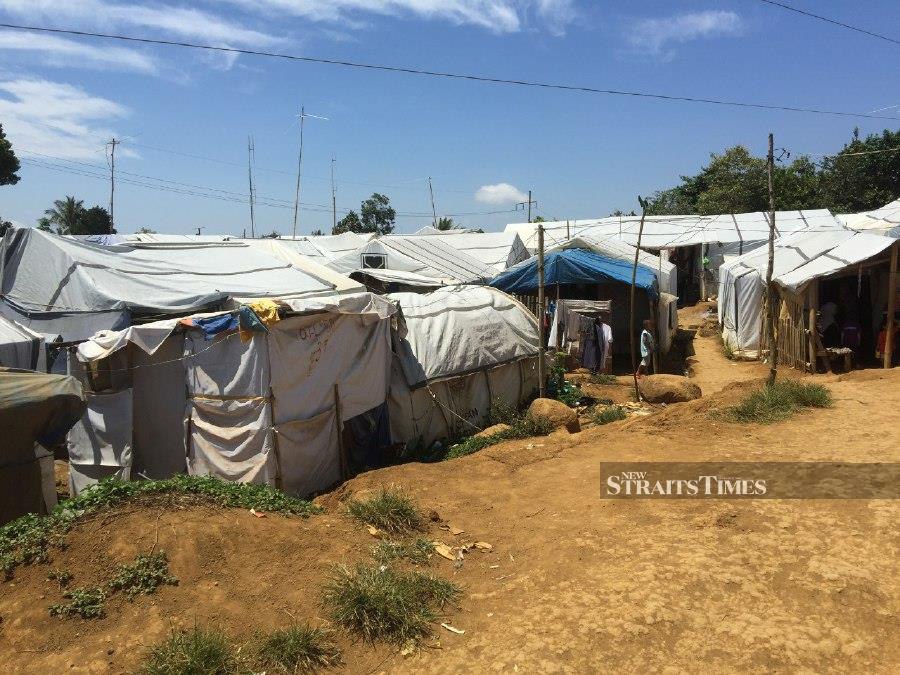

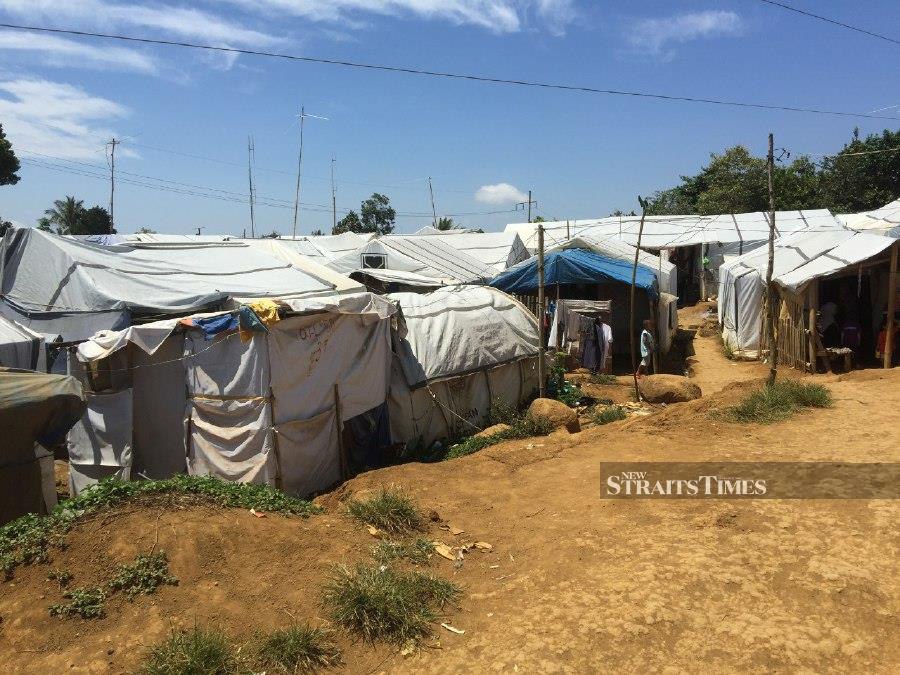

Still, Marawi’s returned are in a better position than the majority of Maranao who cannot yet erase their label of “Internally-Displaced Persons” (IDPs). According to the ICRC, 100,000 of Marawi’s pre-siege population of 350,000 – who formed an exodus after the siege commenced on May 23, 2017 – are still dispossessed. Having fled helter-skelter mainly to adjacent barangays (districts) in the provinces of Lanao del Sur and Lanao del Norte, the refugees either amassed in makeshift tent cities set up in randomly-chosen pockets of undeveloped land; or were hastily taken in by impoverished, but big-hearted, home-based “host communities”. Others sought shelter wherever else they could – from rundown schools to the office buildings of provincial governors.

Almost two years later, there they still languish. With no homes to return to, no money to rebuild their lives with, no means of making money, no families left to take them in, or crippled by fear at the prospect of returning to a former war zone, thousands of IDPs live in a limbo where the most basic necessities are outrageous luxuries, and returning to a normal life is but a distant, impossible dream.

Agonising though their situations were and are, they have been spared worst-case scenarios by the grace of the ICRC.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

Present and prepared

The world was caught largely unawares by the Marawi siege, and the AFP had to scramble to size-up their suddenly-formidable enemy – but the ICRC was well-positioned to handle the fallout. It was a terrible case of being at the wrong place at the right time.

A series of clashes in 2016 between the AFP and the jihadist Maute Group in Butig – a town south of Lake Lanao – had created a minor humanitarian emergency, which necessitated the ICRC’s intervention. Aside from carrying out its prime duty of alleviating the suffering of civilians affected by armed conflict, the organisation doggedly engaged with leaders of militant groups involved in the insurgency – Jemaah Islamiyah, the Maute Group and Islamic State – and initiated “protection dialogues” during lulls in fighting. With the assistance of valiant community leaders and Islamic scholars, the ICRC impressed upon the Muslim extremists the primacy of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) – which designates non-combatants and public facilities such as hospitals as being off-limits to attack; and preserves the rights of prisoners of war – and its numerous points of convergence with Islamic law. Concrete progress was made when the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) formulated and incorporated IHL-based rules of engagement as part of its modus operandi on the battlefield.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

The discourse was also expanded to include the deeply-religious general population of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) – established in 1996 and of which Lanao del Sur is a major component – who looked askance at the ICRC’s alarmingly “Christian” crucifix-like emblem. But when its non-religious nature was finally established through trust-building initiatives, new paths magically opened up, allowing the ICRC access to in-need communities it was previously frustratingly cut off from.

Through its on-the-ground contacts and experience in Butig, the ICRC was able to swiftly assemble and deploy personnel and volunteers – including doctors, consultants and strategists – and respond decisively when all hell broke loose again, this time across the lake, in Marawi.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

Marawi misery

In the first phase of the ICRC’s emergency response to the unfolding siege, focus was placed on providing food, potable water, clothing and the materials for building makeshift shelters for IDPs huddled in areas scattered around Marawi – a tall order, considering that the evacuation was conducted in an utterly-unsystematic everyone-for-himself manner, and few relief centres had been officially designated by the government.

Amidst the mayhem, the ICRC’s next priority was to unite families separated during the rush to flee, as well as to help oversee the evacuation of civilians still trapped in Marawi. Mass medical checks were simultaneously conducted to treat the wounded and prevent the spread of diseases which tend to rear their heads amidst unsanitary living conditions.

As the war dragged on, the ICRC supervised the transfer of stranded or still-homeless refugees to proper Temporary Evacuation Areas, the largest of which are in the barangays of Bito and Sagonsongan. Improvements to the sprawling camps were gradually made – supervised by ICRC’s Water and Habitat Engineers – and regular shipments of supplies were secured. Large-scale projects such as the digging of boreholes for the provision of potable water were launched, in consultation with the IDPs, who communicated their needs, shared their knowledge of the lay of the land, and contributed much-need manpower.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

When the siege mercifully ended on Oct 23, an irony emerged for the ICRC – the truly back-breaking part of the response had just begun. As the dust settled, it became abundantly clear that Marawi had been pulverised – and there was little of the city to return to. To continue providing basic assistance to the IDPs with no end in sight was an unsustainable solution – and so the second phase of the response was launched.

With a view that the refugees would have to rebuild their lives from scratch whether they choose to return to their broken city or remain at the Temporary Evacuation Areas, the ICRC initiated its Livelihood Assistance Programme, which arms IDPs with the tools needed to make a living. The refugees were provided with vocational training and consultations to either help salvage their former professions, or tackle new ones. After tailoring programmes based on families’ capabilities and unique situations, the provision of occupational tools was arranged – such as nets for fishermen, and plant seeds for farmers. Most notably, for IDPs who met stringent criteria, cash grants of 10,000 Pesos (RM786) were provided as capital to kick-start small enterprises – the establishment and running of which were closely guided by the ICRC’s Economic Security Officers.

Concurrently, prior to the permitted return of 64,000 IDPs to areas just outside of the MAA, the ICRC joined Task Force Bangon Marawi and other NGOs and government agencies in ensuring that basic utility services and sanitation were restored and crucial infrastructure repaired.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

Still waters

Interestingly, the two greatest challenges the ICRC found itself tackling were invisible, so to speak.

The first was an insidious presence which lurked among IDPs who spoke little, smiled infrequently, slept fitfully and preferred to dwell in the shadows. They were the psychological walking wounded who had endured torture and dehumanisation as hostages and human shields; and witnessed the destruction of all they had owned, or the savage murder of all whom they had loved. Others seethed from the indignity and humiliation of dispossession; while more still agonised over what the future held.

With scores of IDPs hobbled by disorders notoriously tough to diagnose and even harder to treat; and sufferers leery of stigmatisation in a society still equating psychological illness with lunacy, the ICRC was faced with a headscratcher.

But with the oversight of clinical psychologists and Protection Coordinators, IDPs who presented with symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, depression and anxiety were generously assisted in coping with their ruinous flashbacks and the complications of their present situations. “Psychosocial sensitisation” sessions at various camps were organised for individuals, families and entire communities for mental torments to be expressed and processed; while Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) was employed to liberate patients – especially youth – from their disabling psychopathy. Awareness campaigns were also conducted to draw mental-disorder sufferers from their hiding places, and help communities familiarise themselves with the symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety.

A second equally-Herculean, intangible complication faced by the ICRC was grappling with the calamitous legal limbo faced by IDPs robbed of important documents, property and kin. Without official papers or surviving family members, the Maranao found themselves in a tangle of administrative dead-ends on matters of property ownership, inheritance, guardianship of children, remarriage, education, employment and overseas travel – under both Sharia and Common Law. On paper, they did not exist – making their brighter future unreachable.

NSTP/Jafwan Jaafar

Undaunted, the ICRC boosted its response and rehabilitation programme on a number of fronts. It cranked up efforts in tracing the thousands still missing and reuniting fractured families; and intensified its process of positively identifying hundreds of remains of the unknown. It directed IDPs to relevant agencies and helped facilitate complex legal procedures; while reminding government departments of their obligations to the Maranao. It expanded its Livelihood Assistance Programme to profile greater numbers of prospective small-scale entrepreneurs; and offered vocational training at a growing number of venues. It hired more IDPs as part of the construction of everything from sanitation systems to bore holes, and consulted them on new projects in ways that bestowed them with a sense of ownership over the rebuilding process. And the ICRC worked with community heads in identifying households desperate for assistance and the nature and magnitude of their problems; and deployed volunteers to “accompany” families in their struggle to pick up the pieces.

The Maranao’s ‘Back to the Future’ trek to the Marawi of yore has only just begun with a juddering start – but with the ICRC as co-pilot, their hard-won homecoming is just a matter of time.

https://www.nst.com.my/world/2019/04/477454/malaysians-and-world-have-forgotten-about-marawi-heres-reminder-1-2