From Rappler (Dec 20, 2022): FAST FACTS: Things to know about the Communist Party of the Philippines (By JODESZ GAVILAN)

The Communist Party of the Philippines says Filipinos face three basic problems – imperialism by the US, feudalism, and bureaucratic capitalism

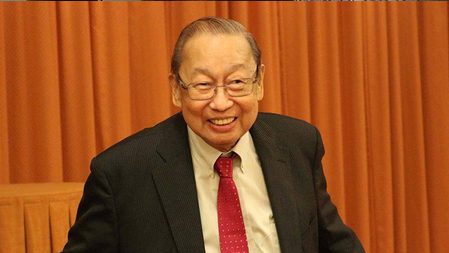

The Communist Party of the Philippines says Filipinos face three basic problems – imperialism by the US, feudalism, and bureaucratic capitalismMANILA, Philippines – The death of exiled communist leader Jose Maria “Joma” Sison on December 16 sparked discussions and questions about the future of the communist movement in the Philippines.

Sison was the founding chairperson of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and a leading figure in the communist movement in the country. He went into exile in the Netherlands in 1987, after going on a lecture tour in Asia and Europe upon his release from prison by the Corazon Aquino administration in 1986.

Sison died on December 16 (December 17, Manila time) in Utrecht, the Netherlands, far away from a country where he started Asia’s longest communist insurgency. But what else do we need to know about the CPP?

How did the CPP start?

The CPP was created on December 26, 1968 – three years after the dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos was elected into the presidency. It would gather strength and power throughout the dark Martial Law years.

The CPP was established by Sison, a leading youth activist, following his departure from the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas-1930, a group created in response to a need for “workers and peasants to lead the anti-imperialist struggle for national independence.”

The first national congress of the CPP was held in Alaminos, Pangasinan. It is in national congresses where members of the central committee – the main decision-making authorities in the party – are elected. The committee convenes these congresses every five years.

There are also about 16 regional committees under the CPP.

What is the goal of the CPP?

The CPP follows Marxism-Leninism-Maoism as its “guide to action,” according to its constitution. It also says that “it is the supreme task of the [CPP] to apply this theory on the concrete conditions of the [country] and to integrate it with the concrete practice of the Philippine revolution.”

For the communist group, the Philippines remains a “semi-colonial and semi-feudal” country where citizens are oppressed by US imperialism, feudalism or when people in the countryside can never own the land they work on, and bureaucratic capitalism, where select elite capitalists hold political positions thus only serving the ruling classes.

The CPP laid out possible solutions to these basic problems through its Program for a People’s Democratic Revolution, which calls for the implementation of genuine land reform and national industrialization, among others. The group also calls for the establishment of the people’s democratic government, instead of what it calls a “ruling neocolonial state.”

“All Filipino communists must work and struggle to realize this long-term program and must be ready to sacrifice their lives if necessary in the struggle to bring about a new Philippines that is completely independent, democratic, united, just and prosperous,” the PPDR read.

What is the role of the New People’s Army in the CPP?

The New People’s Army (NPA) is the armed wing of the CPP and has been involved in clashes with the military since the beginning of Asia’s longest-running communist insurgency.

According to the CPP constitution, the NPA is its “main weapon…in the seizure and consolidation of political power,” wielding “the basic alliance of the working class and the peasantry” to create conditions for the people’s democratic state “by waging armed struggle, facilitating agrarian revolution, and helping build organs of political power and revolutionary mass organizations.”

It was created on March 29, 1969 in Capas, Tarlac with about 60 combatants. The numbers grew and even reached at least 25,000 in the late 1980s, but membership has since dwindled.

What are the controversies the CPP and the CPP-NPA faced over the years?

The group behind Asia’s longest communist insurgency is not without its controversies. The CPP and its armed wing NPA have been the subject of countless criticisms over more than half a decade of existence.

There was the bloody internal purge in the 1980s, where many mostly young members were killed on the unfounded suspicion that they were undercover state agents tasked to penetrate the communist group.

In an interview with Newsbreak magazine in 2002, Sison told journalist and now Rappler executive editor Glenda Gloria that what happened was “something regrettable.”

“But I should not regret it personally [because] I was not around…. I was not informed,” he said.

In the 1990s, the CPP also had a bitter split that created factions in the communist movement due to deviations in strategy on how to achieve its goal. The reaffirmists (RAs) want to follow Sison’s call to go back to the basic principles – including the protracted people’s war while rejectionists (RJs) did not accept Sison’s sweeping analysis and conclusions.

Did the CPP ever engage in peace talks?

The CPP has tried to engage in peace negotiations with the Philippine government over several administrations since its establishment, except during the Marcos dictatorship. The group was represented by the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) in these talks.

The peace talks during the Corazon Aquino administration were unsuccessful. Meanwhile, the Ramos presidency saw a more positive development, especially with the repeal of the Anti-Subversion Act, in 1992. Then-president Fidel Ramos assured communist insurgents of political space. He said then that he “challenges them to compete under our constitutional system and free market of ideas – which are guaranteed by the rule of law.”

It was under the Ramos administration when two important agreements were signed: the Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees (JASIG) and the Comprehensive Agreement to Respect Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (CARHRIHL).

But talks stalled afterwards, including during the Estrada administration. The peace negotiations under the Arroyo administration broke down due to the terrorist tag of the US, and the non-release of political prisoners under the second Aquino administration.

The CPP enjoyed having positive relations during the first few months of the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte – who openly called himself a leftist. He once referred to the communist movement as a “revolutionary government.”

The Philippine government and the NDF started the first rounds of talks in August 2016 in Oslo, Norway. Several high-ranking officials were earlier released from prison to participate in the talks, including Benito and Wilma Tiamzon, who were first arrested in March 2014.

“Our friendship has a strong basis in long-standing cooperation and in a common desire to serve the national and democratic rights and best interests of the Filipino people,” Sison said in August 2016.

But this was short-lived as the initiated ceasefires from both sides were lifted in February 2017. Sison and Duterte, former student of Sison himself, then went back to exchanging verbal insults, while the Duterte government and its allies engaged in massive red-tagging and a violent crackdown on progressive groups, human rights activists, students, and journalists, among others.

What’s next for the CPP post-Joma?

The death of Joma Sison marks another chapter for the communist movement. But there are several discourses on what it could mean – the start of the end, or a new beginning for Asia’s longest-running insurgency.

CPP spokesperson Marco Valbuena said in a statement that the movement vows to “continue to give all our strength and determination to carry the revolution forward guided by the memory and teachings of the people’s beloved Ka Joma.”

The Department of National Defense, meanwhile, said that Sison’s death removes “the greatest stumbling block [to] peace” in the Philippines, adding that “we will all be the better for it.”

Sison’s death comes ahead of the CPP’s 54th anniversary on December 26. We wait for what happens next.

https://www.rappler.com/nation/things-to-know-communist-party-philippines/