From Rappler (Jul 8):

FULL TEXT: The Philippines' opening salvo at The Hague

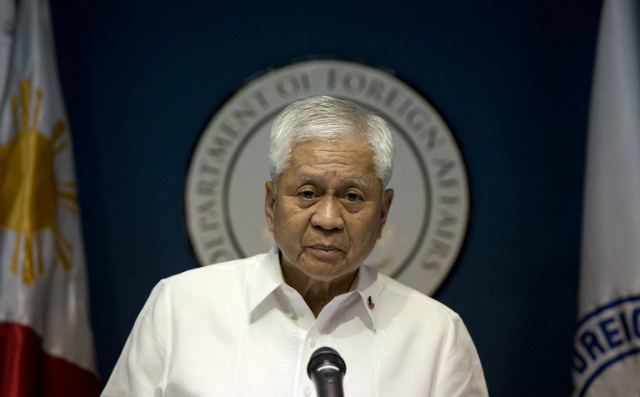

TOP DIPLOMAT. Philippine Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario gives a statement about the South China Sea during a news conference in Manila on March 30, 2014. File photo by Noel Celis/AFP

Below is the full text of Philippine Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario's statement before an arbitral tribunal at The Hague, The Netherlands, on the Philippines' case against China. Del Rosario delivered this speech – originally titled "Why the Philippines Brought This Case to Arbitration and Its Importance to the Region and the World" – on July 7, the first day of oral hearings at The Hague.

TOP DIPLOMAT. Philippine Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario gives a statement about the South China Sea during a news conference in Manila on March 30, 2014. File photo by Noel Celis/AFP

Below is the full text of Philippine Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario's statement before an arbitral tribunal at The Hague, The Netherlands, on the Philippines' case against China. Del Rosario delivered this speech – originally titled "Why the Philippines Brought This Case to Arbitration and Its Importance to the Region and the World" – on July 7, the first day of oral hearings at The Hague.

1. Mr President,

distinguished Members of the Tribunal, it is a great honor to respectfully

appear before you on behalf of my country, the Republic of the Philippines. It

is indeed a special privilege to do so in a case that has such importance to

all Filipinos and – if I may add – to the rule of law in international

relations.

2. Mr President,

the Philippines

has long placed its faith in the rules and institutions that the international

community has created to regulate relations among States. We are proud to have

been a founding member of the United Nations, and an active participant in that

indispensable institution.

3. Its organs,

coupled with the power of international law, serve as the great equalizer among

States, allowing countries, such as my own, to stand on an equal footing with

wealthier, more powerful States.

4. Nowhere is

this more true, Mr President, than with respect to the progressive development

of the law of the sea, which culminated in the adoption of the Law of the Sea

Convention in 1982. That instrument, which has rightly been called a

“Constitution for the Oceans,” counts among its most important achievements the

establishment of clear rules regarding the peaceful use of the seas, freedom of

navigation, protection of the maritime environment and, perhaps most

importantly, clearly defined limits on the maritime areas in which States are

entitled to exercise sovereign rights and jurisdiction.

5. These are all

matters of central significance to the Philippines. Indeed, given our

lengthy coastline, our status as an archipelagic state, and our seafaring

tradition, the rules codified in the law of the sea have always had particular

importance for the Philippines.

The Philippines

is justifiably proud of the fact that it signed the Convention on the day it

was opened for signature, on December 10, 1982, and was one of the first States

to submit its instrument of ratification, which it did on May 8, 1984.

6. The Philippines has

respected and implemented its rights and obligations under the Convention in

good faith. This can be seen in the amendment of our national legislation to

bring the Philippines’ maritime claims into compliance with the Convention, by

converting our prior straight baselines into archipelagic baselines in

conformity with Articles 46 and 47, and by providing that the maritime zones of

the Kalayaan Island Group and Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea would be

consistent with Article 121.

7. The Philippines

took these important steps, Mr President, because we understand, and accept,

that compliance with the rules of the Convention is required of all States

Parties.

8. I mentioned a

moment ago the equalizing power of international law. Perhaps no provisions of

the Convention are as vital to achieving this critical objective than Part XV.

It is these dispute resolution provisions that allow the weak to challenge the

powerful on an equal footing, confident in the conviction that principles trump

power; that law triumphs over force; and that right prevails over might.

9. Mr President,

allow me to respectfully make it clear: in submitting this case, the Philippines is NOT asking the Tribunal to

rule on the territorial sovereignty aspect of its disputes with China.

10. We are here

because we wish to clarify our maritime entitlements in the South

China Sea, a question over which the Tribunal has jurisdiction.

This is a matter that is most important not only to the Philippines, but also to all coastal States that

border the South China Sea, and even to all

the States Parties to UNCLOS. It is a dispute that goes to the very heart of

UNCLOS itself. Our very able counsel will have much more to say about this

legal dispute over the interpretation of the Convention during the course of

these oral hearings. But in my humble layman’s view, the central legal dispute

in this case can be expressed as follows:

11. For the Philippines,

the maritime entitlements of coastal States – to a territorial sea, exclusive

economic zone, and continental shelf, and the rights and obligations of the

States Parties within these respective zones – are established, defined, and

limited by the express terms of the Convention. Those express terms do not

allow for – in fact they preclude – claims to broader entitlements, or

sovereign rights, or jurisdiction, over maritime areas beyond the limits of the

EEZ or continental shelf. In particular, the Convention does not recognize, or

permit the exercise of, so-called “historic rights” in areas beyond the limits

of the maritime zones that are recognized or established by UNCLOS.

12. Sadly, China disputes

this, Mr President, in both word and deed. It claims that it is entitled to

exercise sovereign rights and jurisdiction, including the exclusive right to

the resources of the sea and seabed, far beyond the limits established by the

Convention, based on so-called “historic rights” to these areas. Whether these

alleged “historic rights” extend to the limits generally established by China’s

so-called “9-dash line,” as appears to be China’s claim, or whether they

encompass a greater or a narrower portion of the South China Sea, the

indisputable fact, and the central element of the legal dispute between the

Parties, is that China has asserted a claim of “historic rights” to vast areas

of the sea and seabed that lie far beyond the limits of its EEZ and continental

shelf entitlements under the Convention.

13. In fact, China has done

much more, Mr President, than to simply claim these alleged “historic rights.”

It has acted forcefully to assert them, by exploiting the living and non-living

resources in the areas beyond the UNCLOS limits while forcibly preventing other

coastal States, including the Philippines, from exploiting the resources in the

same areas – even though the areas lie well within 200 M of the Philippines’

coast and, in many cases, hundreds of miles beyond any EEZ or continental shelf

that China could plausibly claim under the Convention.

14. The legal

dispute between the Philippines

and China over China’s claim to and exercise of alleged

“historic rights” is a matter falling under the Convention, and particularly

Part XV, regardless of whether China

is claiming that “historic rights” are recognized under the Convention, or

allowable under the Convention because they are not precluded by it. China has made

both arguments in its public statements. But it makes no difference for

purposes of the characterization of this dispute as one calling for the

interpretation or application of the Convention. The question raised by the

conflicting positions of the Philippines

and China

boils down to this: Are maritime entitlements to be governed strictly by

UNCLOS, thus precluding claims of maritime entitlements based on “historic

rights”? Or does the UNCLOS allow a State to claim entitlements based on

“historic” or other rights even beyond those provided for in the Convention

itself?

15. As our

counsel will explain, Mr President, any recognition of such “historic rights”

conflicts with the very character of UNCLOS and its express provisions

concerning the maritime entitlements of coastal States. This calls indisputably

for the proper interpretation of the fundamental nature of the Convention.

16. China’s assertion and exercise of its alleged

rights in areas beyond its entitlements under UNCLOS have created significant

uncertainty and instability in our relations with China and in the broader region. In

this respect, I note the presence here today of representatives of Vietnam, Malaysia,

Indonesia, Thailand, and Japan to observe these critical

proceedings.

17. Mr President, China has claimed “historic rights” in areas

that are beyond 200 M from its mainland coasts, or any land feature over which

it claims sovereignty, and within 200 M of the coasts of the Philippines’ main islands, and exploited the

resources in these areas while preventing the Philippines from doing so. It has

therefore, in the Philippines’

view, breached the Convention by violating Philippine sovereign rights and

jurisdiction. China

has pursued its activities in these disputed maritime areas with overwhelming

force. The Philippines

can only counter by invoking international law. That is why it is of

fundamental importance to the Philippines, and we would submit, for the rule of

law in general, for the Tribunal to decide where and to what limit China has

maritime entitlements in the South China Sea; where and to what limit the

Philippines has maritime entitlements; where and to what extent the Parties’

respective entitlements overlap and where they do not. None of this requires or

even invites the Tribunal to make any determinations on questions of land

sovereignty, or delimitation of maritime boundaries.

18. The Philippines

understands that the jurisdiction of this tribunal convened under UNCLOS is

limited to questions that concern the law of the sea. With this in mind, we

have taken great care to place before you only claims that arise directly under

the Convention. As counsel for the Philippines will discuss at length

in the coming days, we have, in essence, presented five (5) principal claims.

They are:

– First, that China is not

entitled to exercise what it refers to as “historic rights” over the waters,

seabed, and subsoil beyond the limits of its entitlements under the Convention;

– Second, that the

so-called 9-dash line has no basis whatsoever under international law insofar

as it purports to define the limits of China’s claim to “historic rights”;

– Third, that the

various maritime features relied upon by China as a basis upon which to assert

its claims in the South China Sea are not islands that generate entitlement to

an exclusive economic zone or continental shelf. Rather, some are “rocks”

within the meaning of Article 121, paragraph 3; others are low-tide elevations;

and still others are permanently submerged. As a result, none are capable of

generating entitlements beyond 12M, and some generate no entitlements at all. China’s recent

massive reclamation activities cannot lawfully change the original nature and

character of these features;

– Fourth, that China has breached the Convention by interfering

with the Philippines’

exercise of its sovereign rights and jurisdiction; and

– Fifth, that China has irreversibly damaged the regional

marine environment, in breach of UNCLOS, by its destruction of coral reefs in

the South China Sea, including areas within the Philippines’ EEZ, by its

destructive and hazardous fishing practices, and by its harvesting of

endangered species.

19. Mr President,

the Philippines is committed

to resolving its disputes with China

peacefully and in accordance with international law. For over two decades, we

diligently pursued that objective bilaterally, regionally, and multilaterally.

I will not here take this Tribunal through the Philippines’ painstaking and

exhaustive diplomatic efforts, which are set out in detail in our written

pleadings. I will, however, mention a few representative examples, if I may.

20. As far back

as August 1995, after China seized and built structures on Mischief Reef – a

low-tide elevation located 126 nautical miles from the Philippine island of

Palawan and more than 600 nautical miles from the closest point on China’s

Hainan Island – the Philippines sought to address China’s violation of its

maritime rights diplomatically. During those exchanges, the Philippines and

China agreed that the dispute should be resolved in accordance with UNCLOS. As

the then Chinese Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs, Mr Tang Jiaxuan, stated two

years later during bilateral negotiations, China and the Philippines should

“approach the disputes on the basis of international law, including the United

Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, particularly its provisions on the

maritime regimes like the exclusive economic zone.”

21. The mutual

acceptance that the Philippines’ disputes with China must be resolved in

accordance with UNCLOS was also reflected in a Joint

Communiqué issued in July 1998 upon completion of bilateral

discussions between my predecessor, Foreign Secretary Domingo Siazon, and

China’s Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxuan. The Communiqué recorded that, and I

quote, “The two sides exchanged views on the question of the South China Sea

and reaffirmed their commitment that the relevant disputes shall be settled

peacefully in accordance with the established principles of international law,

including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.” (End of quote)

22. Regrettably,

neither the bilateral exchanges I have mentioned, nor any of the great many

subsequent exchanges, proved capable of resolving the impasse caused by China’s

intransigent insistence that China alone possesses maritime rights in virtually

the entirety of the South China Sea, and that the Philippines must recognize

and accept China’s sovereignty before meaningful discussion of other issues

could take place.

23. The

Philippines has also been persistent in seeking a diplomatic solution under the

auspices of ASEAN. This has proven no more successful than our bilateral

efforts. In fact, China has insisted that ASEAN cannot be used to resolve any

territorial or maritime disputes concerning the South China Sea, and that such

issues can only be dealt with in bilateral negotiations. ASEAN and China have

yet to conclude a binding code of conduct in the South China Sea. The most that

has been achieved was the issuance, in 2002, of a “Declaration on the Conduct

of Parties in the South China Sea.” Although that document recorded the

parties’ commitment to work toward the “eventual” establishment of a code of

conduct in the South China Sea, China’s intransigence in the 13 years of

subsequent multilateral negotiations has made that goal nearly unattainable.

24. Nonetheless,

Mr President, the 2002 DOC is significant in at least one important respect:

the ASEAN Member States and China undertook therein to “resolve their territorial

and jurisdictional disputes by peaceful means, without resorting to the threat

or use of force, through friendly consultations and negotiations by sovereign

states directly concerned, in accordance with universally recognized principles

of international law, including the 1982 UN

Convention on the Law of the Sea.” In so doing, the Declaration

encouraged those States, should they prove unable to resolve their disputes

through consultations or negotiations, to do so in accordance with the

Convention, which includes, of course, the dispute resolution procedures under

Part XV.

25. Mr President,

over the years, China’s positions and behavior have become progressively more

aggressive and disconcerting. Outside observers have referred to this as

China’s “salami-slicing” strategy: that is, taking little steps

over time, none of which individually is enough to provoke a crisis. Chinese

military officials themselves have referred to this as its “cabbage” strategy:

peeling one layer off at a time. When these small steps are taken together,

however, they reflect China’s efforts to slowly consolidate de facto control throughout the South China

Sea.

26. Two more

recent incremental steps caused the Philippines to conclude that it had no

alternative other than to invoke compulsory procedures entailing a binding

decision. The first was China’s transmittal of its 9-dash line claim to the

United Nations in 2009, after which, it prevented the Philippines from carrying

out long-standing oil and gas development projects in areas that are well

inside the Philippines’ 200 M EEZ and continental shelf.

27. Secondly, in

2012, China forcibly expelled Philippine fishermen from the maritime

areas around Scarborough Shoal where the Filipino fishermen have for

generations been fishing without so much as a protest from China.

28. These and

other acts by China caused the Philippines to conclude that continued

diplomatic efforts, whether bilateral or multilateral, would be futile, and

that the only way to resolve our maritime disputes was to commence the present

arbitration.

29. Subsequent

events, including China’s acceleration of massive land reclamation activities,

which it has undertaken – and continues to undertake – in blatant disregard of

the Philippines rights’ in its EEZ and continental shelf, and at tremendous cost to the marine environment in violation of UNCLOS –

only serve to reconfirm the need for judicial intervention.

30. Mr President,

I would like to conclude by conveying my country’s deepest appreciation for the

considerable time and attention you have devoted to these proceedings. The case

before you is of the utmost importance to the Philippines, to the region, and

to the world. In our view, it is also of utmost significance to the integrity

of the Convention, and to the very fabric of the “legal order for the seas and

oceans” that the international community so painstakingly crafted over many

years.

31. If China can

defy the limits placed by the Convention on its maritime entitlements in the

South China Sea, and disregard the entitlements of the Philippines under the

Convention, then what value is there in the Convention for small States Parties

as regards their bigger, more powerful and better armed neighbors? Can the

Philippines not invoke Part XV to challenge China’s activities as violations of

its obligations and the Philippines’ rights, considering that the Philippines’

claims call for a mere interpretation and application of the Convention and do

not fall within any of the jurisdictional exclusions of Articles 297 or 298?

32. Mr President,

if the Philippines cannot invoke Part XV, then what remains of the obligation

regarding judicial settlement of disputes that was such a key element of the

comprehensive package that made the Convention acceptable to all State Parties?

33. We

understand, Mr President, that in the exercise of its collective wisdom and

judgment, this body has decided to bifurcate the proceedings and to limit these

current hearings to the issue of jurisdiction. In this respect, we shall

explain in full how our case falls squarely within the jurisdiction of this

Tribunal, to the end that justice and fair play may prevail and the Tribunal

would recognize its jurisdiction over the case and allow the Philippines to

present the actual merits of our position.

34. In the

Philippines’ view, it is not just the Philippines’ claims against China that

rest in your capable hands. Mr. President, it is the spirit of UNCLOS itself.

That is why, we submit, these proceedings have attracted so much interest and

attention. We call on the Tribunal to kindly uphold the Convention and enable

the rule of law to prevail.

35. I humbly

thank you, Mr President, and distinguished Members of the Tribunal. May I now

ask that Philippines’ counsel, Mr. Paul Reichler, be called to the podium.

http://www.rappler.com/nation/98769-philippines-china-hague-opening-statement-full-text