Opinion piece posted to MindaNews (Feb 20, 2024: PEACETALK: The Jolo Siege of 1974, Half a Century Hence: Notes on History, War, Peace, Law and Justice (1) (By SOLIMAN M. SANTOS JR.)

(First of two parts)NAGA CITY (MindaNews /20 February) – On the occasion of the 50th anniversary commemoration of “The Siege of Jolo 1974: A Forum and Webinar with Survivors and Victims” was held on 12 February 2024 at Bocobo Hall, Law Center, University of the Philippines (U.P.), Diliman, Quezon City. This was planned, organized and sponsored primarily by the Bantayog ng mga Bayani Foundation, in cooperation with the Philippine Center for Islam and Democracy (PCID), the Human Rights Violations Victims Memorial Commission (HRVVMC), the U.P. Law College of Law/ Law Center Institute for Judicial Administration (IJA), and the De La Salle University (DLSU) Bienvenido N. Santos Creative Writing Center.

Bantayog Executive Director Ma. Cristina “May” V. Rodriguez, in her opening message, started by revealing an earlier received email cautionary note from a traumatized survivor saying “Please allow us to heal; please do not prick our pain for whatever reason or intentions you may have.” Then May went on to eventually say, “… with this webinar, we hope to contribute in filling up the gaps in our immediate past, or even to help in correcting the historical distortions that have been fed to us. For if we do not know the truths about our past, if all we know are based on lies, how good are our decisions, how wise are our opinions, how helpful are our actions? … I know very little more today about Jolo than I did then. But I hope that today, our respected survivors and other speakers will help clear this haze in my mind and in the minds of many others of my generation and subsequent generations who have been the victims of the deceptions or cover-ups that official history has put on Jolo of 1974.” PCID President Amina Rasul Bernardo, herself from Jolo, in her message and introduction to the webinar, emphasized precisely its point being to “never forget” so that it “never again” gets repeated.

I had the privilege and honor of being part of the Forum’s panel discussion moderated by Bantayog’s research director Dr. Juan A. Perez III that included three civilian resident survivors Ambroussi “Cheng” Rasul, Dorothy Lim Gokioco, and Rebecca Tan; Agnes Shari Tan Aliman, author of the book The Siege of Jolo, 1974 (Central Books, 2021); and U.P. Visayas history Prof. Elgin Salomon, author of the article “Legitimizing Martial Law: Framing the 1974 Battle of Jolo” in the Bulletin Today and related studies; with the latter two joining online. Fortunately, for those who missed it, the panel discussion has been recorded and this may be accessed via this link:

As I said there, I was not in Jolo in February 1974 but was rather a college junior and student activist in U.P. Diliman, where Amina Rasul was a History subject classmate. Soon after hearing about the Jolo Siege and Burning, including from her, my organization the U.P. Lipunang Pangkasaysayan (LIKAS) joined the campus effort to collect and send relief goods for the displaced victims in solidarity with them. I hardly knew about what really happened in Jolo but it was an initial exposure to what would be eventually referred to as the Bangsamoro problem. I would only much later learn more and deeper about that problem in the course of my civil society-based Mindanao peace advocacy and also postgraduate law studies and continuing scholarly research, that have all resulted in several books. But I still had to read up specifically on the Jolo Siege in preparation for the panel discussion. I share here my notes for and my elaborated talking points at that discussion.

Unfortunately, I have not yet had the chance to read Agnes Aliman’s book. However, I similarly tried to get the several key perspectives of the event from accounts of the two armed protagonists – the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) – and accounts of the Jolo town civilian residents and survivors caught in their crossfire, as well as other keen observers. The MNLF account is found mainly in the Report of the Secretary of the Lupah Sug Revolutionary Committee sent to the Chairman of the Central Committee of the MNLF as quoted in Nur Misuari, “The Rise and Fall of Moro Statehood,” published in Philippine Development Forum, Vol. 6 No. 2, 1992. There is also the Nur Misuari: An Authorized Biography by Tom Stern (Anvil, 2012). The AFP account I referred to is found mainly in the book by former Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) commander Maj. Gen. Delfin Castro (Ret.), A Mindanao Story: Troubled Decades in the Eye of the Storm (2005), esp. its Chapter 1 “The Curtain Rises,” largely based on interviews with the battalion commanders involved. Finally, there is the novel by Criselda Yabes, Below the Crying Mountain (U.P. Press, 2010)which, though fictional in form, is based on factual events in Jolo town and island of the 1970s.

What Really Happened in the Jolo Siege of 1974?

From my reading mainly of the above-said references, the Jolo Siege itself was preceded by the MNLF taking over or occupying of certain municipalities on Jolo island by January 1974. These included mainly the Maimbung-Parang-Indanan triangle to the south of Jolo town and also Luuk in eastern Jolo island. On February 4, 1974, the AFP under Southwestern Command (SOWESCOM) commander Commodore Romulo Espaldon, who was offshore on a naval ship, launched OPLAN CENTURION amphibiously to recover control of those municipalities from the MNLF. The AFP was supported in this by theJolo island “Magic 8” of commanders/ local clan leaders/ mayors whose respective private armed groups were drafted into special paramilitary forces (SPMFs). This AFP operation was largely successful with the MNLF withdrawing from those municipalities by February 6.

The MNLF then decided to attack Jolo town, particularly the Philippine Army 1st Brigade headquarters (HQ) there near the airport. They felt they had to capture Jolo town to demoralize the AFP. Rumors and signs of this possible attack were rife in Jolo town for some days before the actual attack. The MNLF was able to mass a force of an estimated 1,000 men for the attack. Among the identified leaders of this attack force was Alvarez Isnadji, Hadji Van Jajurie and Sical Sahibad. Before dawn of Thursday February 7, 1974, hundreds of MNLF fighters infiltrated Jolo town, including surreptitiously by sea, and established carefully chosen fire-bases. MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari was in his Sabah base near Sandakan, using messengers to direct the battle for Jolo.

MNLF forces to hit the Brigade HQ arrived there at 4:20 A.M. of February 7, but the AFP, particularly the Philippine Air Force (PAF) Sulu Air Task Group (SATAG) in the nearby airport sighted their presence and fired at them, and fighting ensued. The MNLF was able to occupy most of the nearby Notre Dame building, which was well fortified by the AFP, and overlooking both the SATAG and the Brigade HQ. But the MNLF failed to capture a portion of the rooftop containing SATAG’s heavy machinegun and recoilless rifle emplacements covering the approaches to the Brigade HQ. The MNLF practically overrun half of the Brigade. But a Brigade reserve battalion with a tank and an armored personnel carrier (APC) was able to screen the western (left) approach from the Notre Dame building, and so the MNLF forces there were not able to widen their position. Army 4th Infantry Division commander Col. Alfonso Alcoseba, who was at the Brigade HQ when the MNLF attack was launched, took over command of operations in the immediate environs of Jolo town,

At dawn of February 7, another two AFP battalions started a counterattack. Heavy AFP firepower, including jet strafing, forced the MNLF to regroup at the stairways at the right wing of the Notre Dame building. The MNLF then decided to withdraw towards the town center where they were pursued by AFP troops supported by jets and armed helicopters. According to the MNLF, in the AFP’s counter-offensive, artillery shells from the Philippine Navy’s big guns screamed in amongst a rain of rockets. The PAF strafed the city, and used napalm bombs. Howitzers blasted MNLF positions, and fierce hand-to-hand fighting broke out as the Philippine Marines fought to regain Jolo town. Civilians died eating noodles, selling fish, standing around, nursing their children, or riding a tricycle to work. February 7 on to the whole day of Friday February 8, house-to-house fighting in Jolo town center continued.

According to the MNLF, on February 8 afternoon, the AFP, failing to drive the MNLF out of town and having suffered heavy casualties, shot the CALTEX gas station at Serantes St. with a M-79 grenade launcher, then fire ensued which razed down Jolo. Added to this were the incendiary shells of the Navy boats burning Takot-Takot, which practically worsened the fire and burned all houses. According to the AFP, although Jolo town was never completely taken by the MNLF attackers, the government forces were unable to prevent them from burning it as they retreated.

More AFP battalions arrived. According to the AFP, by Saturday February 9, the MNLF forces, reeling from many casualties, including an influential commander Hadji Van Jajurie, then withdrew from Jolo town to Mt. Tumatangis (the “Crying Mountain”), Bud Datu and nearby hills between Jolo and Indanan. Pursuing soldiers and support planes could not fire on them especially in the Mt. Tumatangis area as the MNLF brought along with them civilians, including a priest and four nuns. By Sunday February 10, five AFP battalions joined hands to complete the liberation of Jolo. According to the MNLF, eventually they were forced to move out of Jolo town to guide civilians into safer places so that they would escape the resurgence of massacres perpetrated by the AFP. Chinese, Christians, Muslims and the Catholic parish priest, and four nuns were among the evacuees that the MNLF brought to safer places.

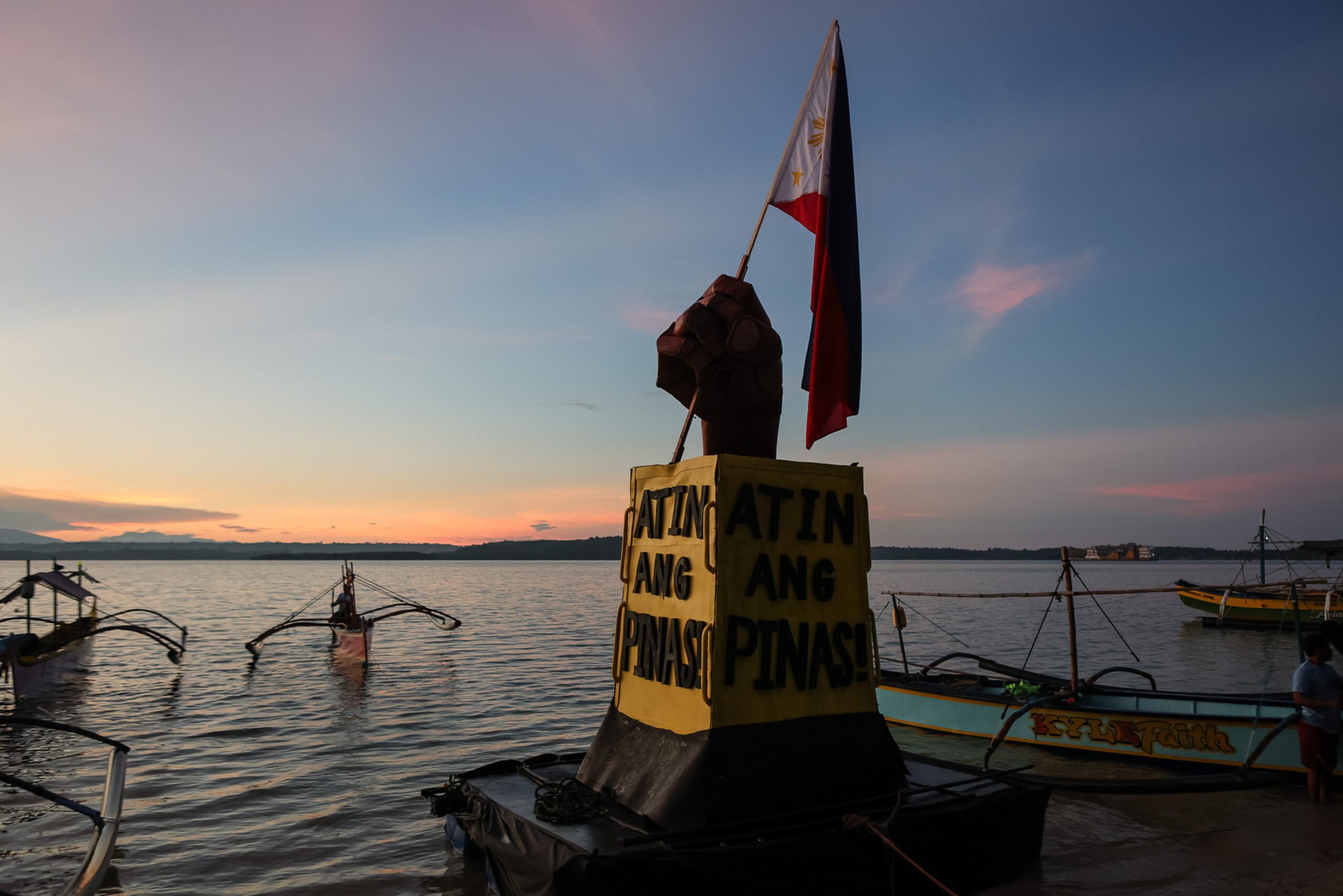

In technicalmilitary terms, the Jolo Siege was not the usual siege where an attacking force surrounds a fortified but static defending force, cutting it off from help and supplies, to lessen its resistance in a sustained and even prolonged way, so as to secure its submission, surrender or capture. The Jolo Siege was more a generic battle, generally a fluid and dynamic encounter, with both sides maneuvering to get the upper hand through attack or counter-attack. But whether a real siege or a standard kind of battle, what is clear was the burning of Jolo town that marked this signal event, aside from the town’s consequent devastation of lives, homes and buildings that constituted the proud center of the Tausug tribe, homeland and heritage.

At last February 12’s Forum on the Jolo Siege, among the background information provided by the organizers were these casualty figures: MNLF killed – 612 (entire campaign); military killed in action – 250; civilians killed – 1,000 to 10,000 (estimates); displaced, rendered homeless in Jolo town – 40,000 (population in 1970 was 46,586); and evacuated to Zamboanga, other places – 6,000. But these are of course not simply numbers. The three survivors in the panel discussion and their stories gave some flesh and life to those numbers.

Impact and Significance on the Growth of the MNLF and on the Armed Conflict in Mindanao

The late MNLF peace panel secretariat head Abraham Iribani, who was a friend, called the Jolo Siege “the mother of all battles” in the early MNLF-led Moro war of national liberation. His poor hardworking parents in Jolo died as a result of that battle. He, who was then 17, was reborn as a Moro student activist upon fleeing to Zamboanga City, like many others displaced from Jolo. The Jolo Battle showed that the MNLF could go head-to-head or head-on in regular mobile and even positional warfare with the AFP. Though beaten back in and from Jolo town and island, with reduced fighting capability such as captured weaponry, the MNLF in Sulu, its Tausug flank under the Lupah Sug Revolutionary Committee, inspired its other flanks, especially the Maguindanao flank in Central Mindanao under the Kutawato Revolutionary Committee, to step up their part of the Moro war of national liberation against the Marcos government of the Philippine state.

The Jolo Siege signified and reaffirmed MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari’s resolve to fight for independence, against the pressure from then Indonesian President Suharto in particular to instead accept Muslim autonomy within the Philippine state. Within a month after the Jolo Siege, in response to its outcome, and decidedly on 18 March 1974, the sixth anniversary of the Jabidah Massacre, he issued what amounted to a “Declaration of Independence,” the MNLF Manifesto on “Establishment of the Bangsamoro Republik.” He said “I wrote the details while I was overseeing the war because foreign leaders wanted to know what we were about.”

The MNLF may have lost the Jolo Battle but it came close to winning its larger war of national liberation. The “New Moro War” of 1972 to 1976 on the two fronts of Southwestern Mindanao and Central Mindanao, after and in response to the declaration of martial law in September 1972, saw the fiercest and bloodiest fighting in the Philippines since World War II and the Japanese occupation of 1942-45. As Central Mindanao (CENCOM) commander Maj. Gen. Fortunato Abat put it, “we [the Philippines] nearly lost Mindanao.” The virtual military stalemate, combined with international factors on the economic (oil crisis and embargo) and diplomatic (Organization of the Islamic Conference intervention) fronts, eventually led to the tripartite Mindanao peace process.

Impact and Significance on the Tripartite Mindanao Peace Process

Within just four months after the Jolo Siege, in June 1974, the intervening Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) in its 5th Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers (ICFM) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysiaissued Resolution No. 18 “On the Plight of the Filipino Muslims,” urging the Philippine government to find a political and peaceful solution through negotiations with the MNLF within the framework of the national sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Philippines. OIC mediation between the two conflicting parties is what has made this Mindanao peace process tripartite.

Within just one year after the Jolo Siege, in January 1975, the First Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) Talks for a political settlement between the Philippine government (represented by then Executive Secretary Alejandro B. Melchor, Jr., who happens to be my late maternal uncle) and the MNLF (Misuari), there was no peace agreement but it paved the way for an eventual one by giving both sides the requisite better understanding of and respect for each other

The breakthrough came with the December 1976 Tripoli Agreement between the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) and the MNLF with the participation of the OIC on the establishment of Autonomy for the Muslims in the Southern Philippines within its national sovereignty and territorial integrity. This was preceded in November 1976 by President Ferdinand Marcos (in)famously sending his First Lady Imelda Marcos to parley with no less than the then Libyan leader Col. Muammar Qaddafi. But it took 20 years more under President Fidel Ramos to complete this peace process with the September 1996 Final Peace Agreement (FPA) with the facilitation of both the OIC and Indonesia. Some would say, “the rest is history,” but it has not been as simple as that, as we have seen or shall see.

Impact and Significance on the Wider Armed Conflict

The Moro armed resistance to martial law during its early years of 1972-76, against which the bulk of the AFP was deployed in Southwestern and Central Mindanao, had the unintended effect of allowing the similarly fledgling Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP)-New People’s Army (NPA) to survive, grow and build up strength in other regions nationwide in Luzon, Visayas and also Mindanao.

Eventually, in the decades since the 1970s, the CPP-NPA has become the main national internal security threat on a nationwide basis, but with Mindanao already for some time now being its strongest island region with the most number of guerrilla fronts. Of course, in Mindanao from 1997 till the March 2014 Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB) between the GRP and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, the latter was the main national internal security threat. But also, for some time already, the armed conflict on the Communist front has covered a much bigger territory and population of Mindanao (Northern and Southeastern) than that covered by the armed conflict on the Moro front (Central and Southwestern Mindanao). Be that as it may, in the past five decades, the Moro armed conflict, with regular mobile and positional warfare, including in urban areas, has tended to be of higher intensity than the Communist armed conflict, with its low-intensity guerrilla warfare in mainly rural areas. Still, the local communist armed conflict in Mindanao is a challenge now also addressed to Mindanao civil society peace advocacy which has for the most part focused on the Moro armed conflict.

Beyond the Philippines, the “New Moro War” of 1972-76, along with other wars of national liberation, notably the Vietnam War which ended in 1975, as well as other internal armed conflicts in the 1960s and 1970s, can be said to be part of the experiential basis for the two 1977 Additional Protocols I and II to the 1949 Geneva Conventions on the rules of war. Protocols I and II provided better and more specific rules for international and non-international armed conflicts, respectively. Protocol I considered as international armed conflicts those situations in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination, in short, wars of national liberation. Precisely, the MNLF of Misuari was organized in the mold of classic national liberation movements of the 1960s like the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) of the late Yasser Arafat and the African National Congress (ANC) of the late Nelson Mandela. In the case of the MNLF, it was a national liberation movement against Filipino colonialism over the Bangsa Moro.

Tomorrow: Watersheds in Philippine and Bangsamoro History: War and Peace

[SOLIMAN M. SANTOS JR. is a retired RTC Judge of Naga City, Camarines Sur, serving in the judiciary there from 2010 to 2022. He has an A.B. in History cum laude from U.P. in 1975, a Bachelor of Laws from the University of Nueva Caceres (UNC) in Naga City in 1982, and a Master of Laws from the University of Melbourne in 2000. He is a long-time human rights and international humanitarian lawyer; legislative consultant and legal scholar; peace advocate, researcher and writer; and author of a number of books, including on the Moro and Communist fronts of war and peace. Among his authored books are The Moro Islamic Challenge: Constitutional Rethinking for the Mindanao Peace Process published by UP Press in 2001; Judicial Activist: The Work of a Judge in the RTC of Naga Citypublished by Central Books in 2023; and his latest, Tigaon 1969: Untold Stories of the CPP-NPA, KM and SDK published by Ateneo Press in 2023]

https://mindanews.com/mindaviews/2024/02/peacetalk-the-jolo-siege-of-1974-half-a-century-hence-notes-on-history-war-peace-law-and-justice-1/#gsc.tab=0

/bnn/media/media_files/466b5d25aad1dcebcf703f72a1cbf94f62a525e091cd6d9de9466fe079ffd786.jpg)