From Rappler (Jul 5):

Does it make sense to talk with the Abu Sayyaf?

The responsible government is the one who keeps looking for a peaceful solution, even if the chances of that taking hold are minimal at this time

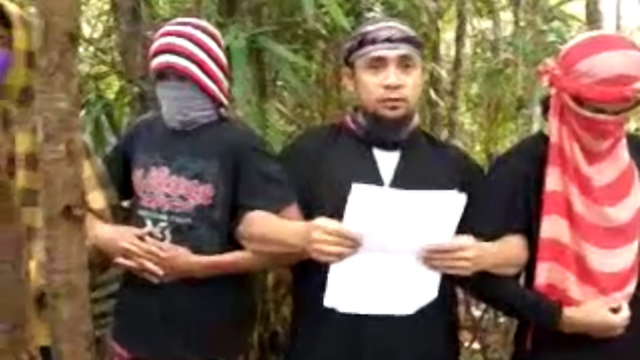

ALLEGIANCE TO ISIS. In this screenshot, ASG leader Isnilon Hapilon (center) is seen in a YoutTube video swearing allegiance to ISIS.

ALLEGIANCE TO ISIS. In this screenshot, ASG leader Isnilon Hapilon (center) is seen in a YoutTube video swearing allegiance to ISIS.

Rodrigo Duterte said days before he became Philippine president that he may be open to

holding talks with the Abu Sayyaf Group, a terrorist band whose leader has sworn allegiance to Islamic State and has a nasty habit of beheading captives if they are not paid millions in ransom.

He told reporters that “I want to ask them are they willing to talk or do we just fight it out.”

The reaction to the idea, which may just be a trial balloon after all, was predictable. Duterte was roundly slammed by several who argue there should be no negotiation with terrorists, especially given the murderous inclinations of the Abu Sayyaf.

The policy position of no negotiations with terrorists has a fairly recent history.

At the height of the Irish Republican Army’s (IRA) bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher also vowed never to negotiate. That pledge has been taken by a variety of governments: Spain with the Basque ETA separatist group and Colombia which just signed an agreement with its own FARC rebel group.

In 2003, US President George W. Bush said of negotiating with terrorists: “You’ve got to be strong, not weak. The only way to deal with these people is to bring them to justice. You can’t talk to them. You can’t negotiate with them.”

The top reasons for not negotiating are that talks would give bands like the Abu Sayyaf a legitimacy they do not deserve.

The talks would also undermine the government, the terrorists are murderers and talking condones or even glosses over their horrendous activities like chopping off the heads of their captors or hostages or blowing up cruise ships, restaurants and other soft targets.

Michael Tomasky, writing in the Daily Beast, said with a touch of asperity that “every (US) president since has said we don’t negotiate with terrorists. And every president has. And I would say prudently and reasonably so.”

“When terrorists can give you information, for a certain price or because you have a shared enemy, take it. George W. Bush paid a ransom of US$300,000 to a radical Islamist group in the Philippines that was holding two American missionaries, a married couple, captive. To get them to safety? I say, fine. Alas, however, the man was killed, even after we paid the money. So an American president ended up financing terrorist operations and overseeing a failed military mission.”

Harmonie Toros of the Department of International Politics at the University of Wales and whose research focuses on this issue pointedly asked about the refusal to talk: “Why the aversion?”

“There is no doubt that a state’s agreeing to engage with an insurgent group would strengthen the latter’s legitimacy claim vis-à-vis the broader national and international community, particularly in democratic states, where there is a greater sense of representation by ordinary citizens.”

“However, the state’s acceptance of a party as a legitimate interlocutor does not automatically confer upon the latter broader legitimacy,” Toros said.

Other than negotiating, the only stance often left on the table is the military option, and if insurgent groups survive for years on end, using force as an option is practically a dead-end. More lives are lost and the fighting prevents the country from reaping any benefits from a peace dividend.

Keeping lines of communication

The question then becomes "can the Philippine government get any benefit from talking to the Abu Sayaf?"

Toros believes talks may be a way to wean away violent groups from their use of violent tactics, no matter how far fetched the idea may be.

She said: “First, negotiations may eliminate one of the reasons why the insurgents may have engaged in violence in the first place (lack of a legal outlet to voice their grievances). Second, they may strengthen the faction in the insurgent group that is in favor of nonviolent engagement. Third, they may draw insurgent groups down a path of change or transformation towards nonviolence.”

While that may not be possible at this time, keeping lines of communication open may eventually convince even intransigent groups like the Abu Sayyaf down the road about the idea of peace.

Rommel Banlaoi, chairman, Philippine Institute for Peace, Violence and Terrorism Research and Director, Center for Intelligence and National Security Studies, makes clear that “holding talks with the ASG does not mean formal peace talks like the way GPH does it with the NDF, MILF and MNLF. Talks with the ASG will be informal to de-radicalize their followers and disengage them from armed activities.”

Audrey Kurth-Cronin, a professor for the US National War College, wrote a few years ago that “it is not at all clear that refusing to ‘talk to terrorists’ shortens their violent campaigns any more than entering into negotiations prolongs them.”

“On the other hand, negotiations can facilitate a process of decline but have rarely been the single factor driving an outcome. The historical record indicates that wise governments approach negotiations as a means to manage terrorist violence over the long term, while a group declines and ceases to exist for other reasons.”

There should be no overflow of optimism the talks with the Abu Sayyaf will accomplish anything. But the idea is to try even if the chances of success are minimal.

The level of violence may be reduced slightly. But the responsible government is the one who keeps looking for a peaceful solution, even if the chances of that taking hold are minimal at this time.

So long as the government is clear-eyed about what it wants in talking to the Abu Sayyaf, fears of giving them legitimacy should not stop the Duterte administration from sitting down and listening to the group.

“The vast majority of negotiations that do occur yield neither clear resolution nor cessation of the conflict. A common scenario has been for negotiations to drag on, occupying an uncertain middle ground between a stable ceasefire and high levels of violence. About half of the groups that negotiated in recent years have continued to be active in their violence as the talks unfolded, usually at a lower level of intensity and frequency – a factor that governments should take into account before talks begin,” Kurth-Cronin said.