Posted to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Website (Jul 13, 2023): The Communist Insurgency in the Philippines//A ‘Protracted People’s War’ Continues

IntroductionWhen Philippine President Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos, Jr. came to power on 30 June 2022, he confronted a decades-long communist insurgency that began during the regime of his father, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. Notably, this insurgency had a mixed fate under Marcos, Jr.’s predecessor, former president Rodrigo Duterte, who initially oversaw ambitious peace talks before a dramatic about-face toward all-out war. Consistent with Duterte’s later turn, Marcos, Jr. has shown little interest so far in resuming formal peace talks with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), alongside its armed wing, the New People’s Army (NPA), and its political wing, the National Democratic Front (NDF), collectively referred to as the CPP-NPA-NDF.1 That disinterest, coupled with the death of CPP founder Jose Maria Sison due to natural causes in December 2022 and the killings of several high-profile rebel leaders in the last three years, raises questions about the road forward for the insurgency.

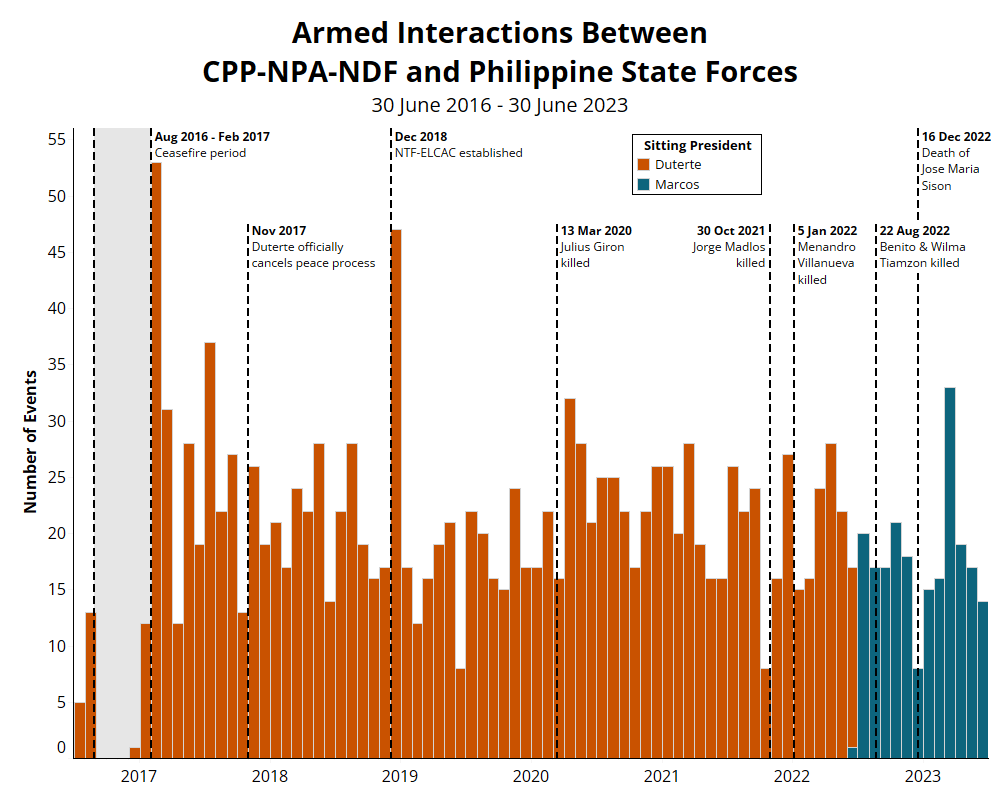

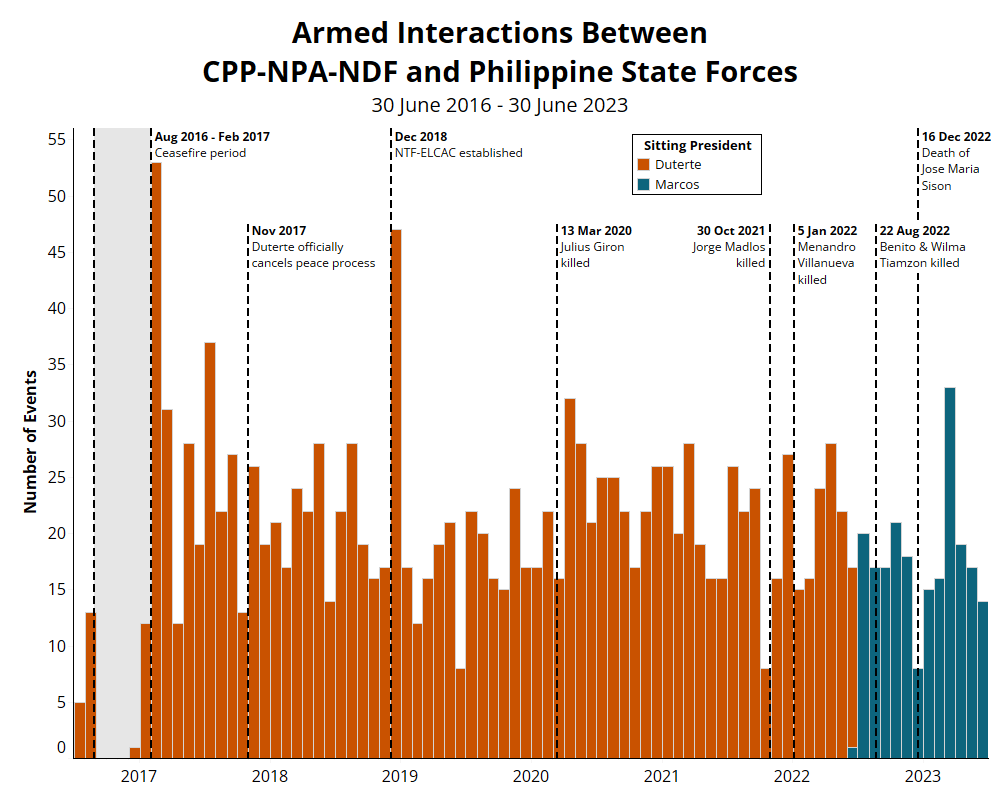

This report examines the fighting between the state and the communist rebels under the Duterte and current Marcos, Jr. administrations. ACLED data show that fighting between state forces and the communist rebels has persisted since the end of the Duterte-era peace talks and into the new Marcos, Jr. regime, though dipping toward the end of 2022 amid the loss of top rebel leaders. A resurgence in fighting occurred in March 2023, while Marcos, Jr. moved to further empower a Duterte-era anti-communist body in May 2023. The report also looks at attacks targeting civilians in the context of the communist insurgency, particularly attacks on activists and other civilian actors related to the state’s practice of red-tagging. Amid this charged political environment, this report concludes by considering the prospects for peace under the Marcos, Jr. regime.

History and Ideology of the CPP-NPA-NDF

The ongoing rebellion being waged by the CPP-NPA-NDF dates back to the early presidency of the late Marcos, Sr., the current president’s father, when Sison reestablished the CPP under a Maoist line on 26 December 1968. The establishment of its armed wing, the NPA, followed on 29 March 1969. Sison’s CPP, which broke away from the older Moscow-aligned Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP) established in 1930, would quickly eclipse PKP in significance and provide a formidable challenge to the Marcos military establishment, growing the NPA to a peak of around 26,000 fighters in the 1980s.2

The CPP’s basic analysis of Philippine society, largely based on Sison’s writings – an application of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism to the Philippine context – has remained largely unchanged since the rebellion started in the late 1960s. The CPP believes the Philippines is a semi-feudal, semi-colonial country, meaning one where formerly feudal structures have been transformed to serve neo-colonial monopoly capitalism. The CPP holds that there are three basic problems in Philippine society: imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat capitalism – to which the answer is a national democratic revolution with a socialist perspective. Their revolution is to be waged in the Maoist vein of a “protracted people’s war,” which involves the gradual encirclement of cities from the countryside, carried out primarily by workers as its leading class and peasants as its main force.3

The basic goals and the fundamental strategy of the protracted people’s war pursued by the CPP-NPA-NDF have remained the same since the insurgency’s inception, and they continue to characterize the movement today. This continuity exists despite a schism in the post-Marcos, Sr. environment of the 1990s that led to a division between the party’s ‘reaffirmists’ (RAs) and the ‘rejectionists’ (RJs), following deadly purges against military infiltrators within the party that brought it to near collapse. The RAs, who reaffirmed Sison’s basic analysis of Philippine society and the strategy of protracted people’s war,4 continue to lead the CPP-NPA-NDF today. The RJs have dispersed into other leftist groupings, often with testy relations with the CPP-NPA-NDF and their allies in the legal, activist, and parliamentary arenas.5 The communists’ specific political program today is expressed in the NDF’s 12-point agenda, which also forms the backbone of the communists’ basic demands in the peace process.6

The endurance of the communist insurgency through several decades is an oft-raised question. By the rebels’ own account, however, this endurance reflects the persistence of the basic problems of Philippine society, which provides fertile ground for the recruitment of peasants and other supportive classes, such as workers and even students from the cities. The strong ideological character of the insurgency seems to ensure an ample supply not only of occasional fighters, but of revolutionaries committed to pursuing their vision for Philippine society long term.7

The national government itself has long acknowledged that the root causes of the armed conflict are related to long-standing socio-economic issues. In the comprehensive Philippine Development Plan of the Duterte administration, the government resolved to implement “peace-promoting and catch-up socio-economic development in conflict-affected areas” as a key measure toward a “just and lasting peace.”8 Meanwhile, the succeeding plan under Marcos, Jr. emphasizes the importance of a reintegration program for surrendering rebels and of socio-economic interventions in barangays (sub-city or sub-town districts) affected by conflict, such as the Barangay Development Fund managed by the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC).9

The continuing sustainability of the NPA insurgency, then, seems to be the result not only of the revolution’s very design as a protracted people’s war, but also of the persistence of conditions that create impoverished rural communities receptive to the CPP-NPA-NDF’s message of revolutionary change.

The ongoing rebellion being waged by the CPP-NPA-NDF dates back to the early presidency of the late Marcos, Sr., the current president’s father, when Sison reestablished the CPP under a Maoist line on 26 December 1968. The establishment of its armed wing, the NPA, followed on 29 March 1969. Sison’s CPP, which broke away from the older Moscow-aligned Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP) established in 1930, would quickly eclipse PKP in significance and provide a formidable challenge to the Marcos military establishment, growing the NPA to a peak of around 26,000 fighters in the 1980s.2

The CPP’s basic analysis of Philippine society, largely based on Sison’s writings – an application of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism to the Philippine context – has remained largely unchanged since the rebellion started in the late 1960s. The CPP believes the Philippines is a semi-feudal, semi-colonial country, meaning one where formerly feudal structures have been transformed to serve neo-colonial monopoly capitalism. The CPP holds that there are three basic problems in Philippine society: imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat capitalism – to which the answer is a national democratic revolution with a socialist perspective. Their revolution is to be waged in the Maoist vein of a “protracted people’s war,” which involves the gradual encirclement of cities from the countryside, carried out primarily by workers as its leading class and peasants as its main force.3

The basic goals and the fundamental strategy of the protracted people’s war pursued by the CPP-NPA-NDF have remained the same since the insurgency’s inception, and they continue to characterize the movement today. This continuity exists despite a schism in the post-Marcos, Sr. environment of the 1990s that led to a division between the party’s ‘reaffirmists’ (RAs) and the ‘rejectionists’ (RJs), following deadly purges against military infiltrators within the party that brought it to near collapse. The RAs, who reaffirmed Sison’s basic analysis of Philippine society and the strategy of protracted people’s war,4 continue to lead the CPP-NPA-NDF today. The RJs have dispersed into other leftist groupings, often with testy relations with the CPP-NPA-NDF and their allies in the legal, activist, and parliamentary arenas.5 The communists’ specific political program today is expressed in the NDF’s 12-point agenda, which also forms the backbone of the communists’ basic demands in the peace process.6

The endurance of the communist insurgency through several decades is an oft-raised question. By the rebels’ own account, however, this endurance reflects the persistence of the basic problems of Philippine society, which provides fertile ground for the recruitment of peasants and other supportive classes, such as workers and even students from the cities. The strong ideological character of the insurgency seems to ensure an ample supply not only of occasional fighters, but of revolutionaries committed to pursuing their vision for Philippine society long term.7

The national government itself has long acknowledged that the root causes of the armed conflict are related to long-standing socio-economic issues. In the comprehensive Philippine Development Plan of the Duterte administration, the government resolved to implement “peace-promoting and catch-up socio-economic development in conflict-affected areas” as a key measure toward a “just and lasting peace.”8 Meanwhile, the succeeding plan under Marcos, Jr. emphasizes the importance of a reintegration program for surrendering rebels and of socio-economic interventions in barangays (sub-city or sub-town districts) affected by conflict, such as the Barangay Development Fund managed by the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC).9

The continuing sustainability of the NPA insurgency, then, seems to be the result not only of the revolution’s very design as a protracted people’s war, but also of the persistence of conditions that create impoverished rural communities receptive to the CPP-NPA-NDF’s message of revolutionary change.

Rural Unrest and Armed Insurgency

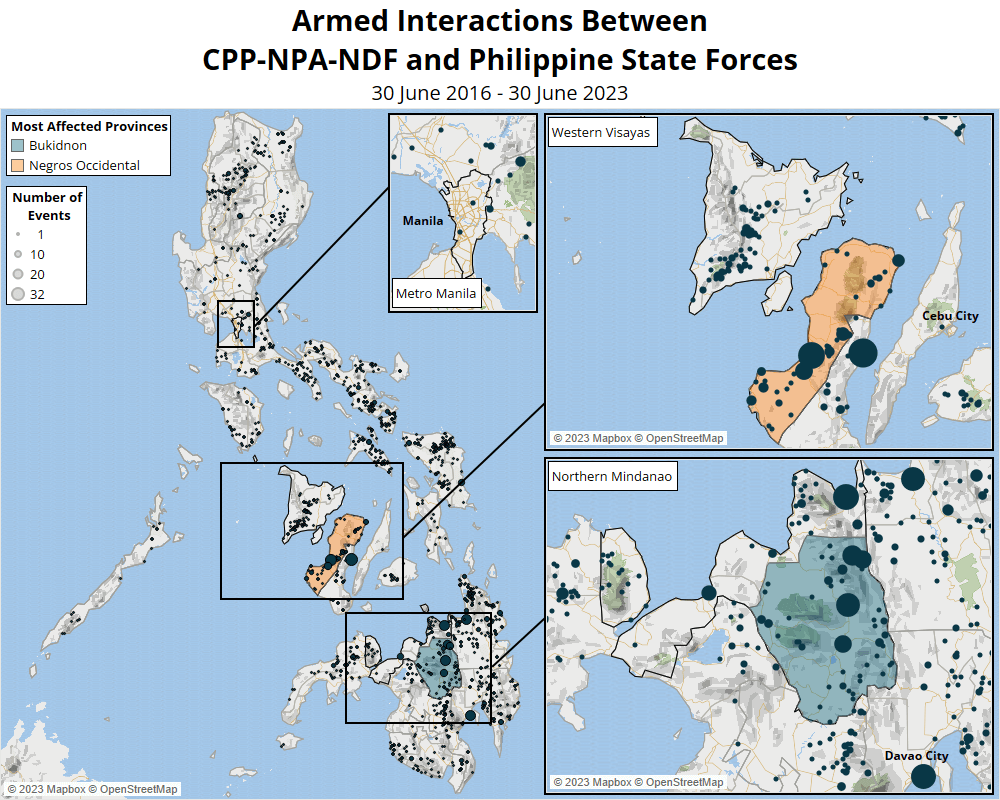

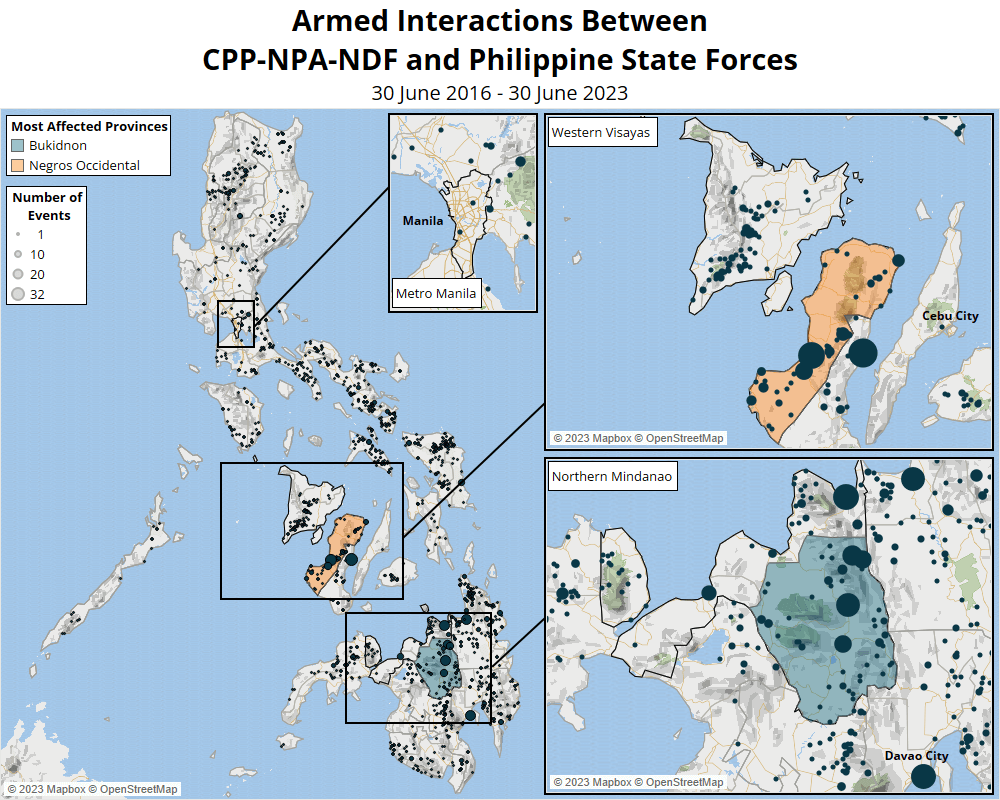

The CPP’s strategy of protracted people’s war stresses the peasantry’s role in providing the revolutionary army’s main force, which then aims to gradually encircle the cities from the countryside as the rebels win over rural communities. This strategy explains the NPA’s scant activity in the biggest urban centers, particularly Metropolitan Manila. Conversely, most clashes between the NPA and the military occur in remote, mountainous terrain in rural agricultural areas, particularly in the western islands of the central Philippines, and in the northern part of the main southern island of Mindanao (see map below).

ACLED data illustrate that the NPA is most active in Negros Occidental province in Western Visayas and Bukidnon province in Northern Mindanao (see inset maps above). This does not come as a surprise for a revolution with an agrarian base. Western Visayas and Northern Mindanao are both known for agrarian unrest, being two of the country’s most important agricultural centers, and therefore serve as ideal staging grounds for the CPP’s revolution. As of 2019, Western Visayas had the largest number of persons employed in agriculture in the country at 873,000, while Northern Mindanao ranked third with 776,000 persons employed in agriculture.10 Additionally, Northern Mindanao and Western Visayas rank among the top three regions in terms of their share of national agricultural production.11

Negros Occidental in Western Visayas is particularly well-known for being the bastion of sugar hacenderos, owners of thousands upon thousands of hectares of sugarcane plantations or haciendas that have provided immense wealth to the local elite since the Spanish colonial era.12 The province continues to have the most haciendas in the Philippines, despite decades of a formal government-sponsored agrarian reform program aiming to solve the problem of farmer landlessness.13 The province still dominates sugar production, accounting for 50.8% of national sugar production in 2014.14

Despite this wealth from sugar production, the province continues to be associated with profound inequality, notorious for widespread famines in the 1980s and continuing abuse, maltreatment, and even outright violence against farm workers during times of unrest.15 A characteristic example is the massacre by unidentified assailants of nine sugarcane farmers of Hacienda Nene, unemployed during the tiempo muerto (the ‘dead season’ between planting and harvesting) in Sagay in October 2018. The incident demonstrates the intersection of agrarian unrest and the communist insurgency. Security forces accused the victims of the Sagay Massacre of being NPA-affiliated provocateurs due to their participation in a bungkalan (collective cultivation work, specifically tilling, on idle lands for survival) as members of the National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW).16 Just a month later, the lawyer of the Sagay Massacre victims, also accused by authorities of being a communist, was also murdered.17

Meanwhile, Northern Mindanao also harbors its share of agrarian issues. Bukidnon, for example, is particularly well-known for its vast pineapple and banana plantations operated by leading transnational corporations such as Del Monte and Dole. However, human rights groups have sounded the alarm over abuses and attacks committed against local farmers and Indigenous peoples in the province by actors with ties to the largest agribusiness players in the region.18

These deep-seated socio-economic issues in Western Visayas and Northern Mindanao continue to persist against the backdrop of widespread poverty among agriculture workers. The latest poverty statistics in the Philippines show that farmers and fishers continue to be the poorest sectors nationally, respectively recording poverty rates of 30.0% and 30.6% in 2021,19 against the national figure of 18.1%.20

Despite the higher levels of fighting between the NPA and state forces in Western Visayas and Northern Mindanao, fighting between both sides was seen in practically all parts of the country from the start of the Duterte regime and into the Marcos, Jr. regime. This means that the NPA has been present in every region, mirroring the prevalence of agrarian issues across the country and widespread poverty of agricultural workers. Sometimes, fighting has even spilled over to the cities, with two of 33 cities classified as highly urbanized – Davao City and Butuan City in Mindanao21 – seeing considerable NPA activity. There is also elevated NPA activity in smaller regional cities, such as Himamaylan, Guihulngan, Gingoog, and Malaybalay.

The NPA’s expansive reach notwithstanding, the military and the communists publicly disagree on the strength of the NPA. In its latest anniversary statement in December 2022, the CPP claimed that the NPA had established 110 fronts across the country, while the party itself had set up committees of leadership and branches in more than 70 out of 82 provinces.22 The military, meanwhile, claimed that the number of NPA fronts is down to 22 as of December 2022.23 In May 2023, the Philippine national security adviser said that of these 22 fronts, the number of “active” guerrilla fronts had gone down to two, while 20 have been “weakened.”24

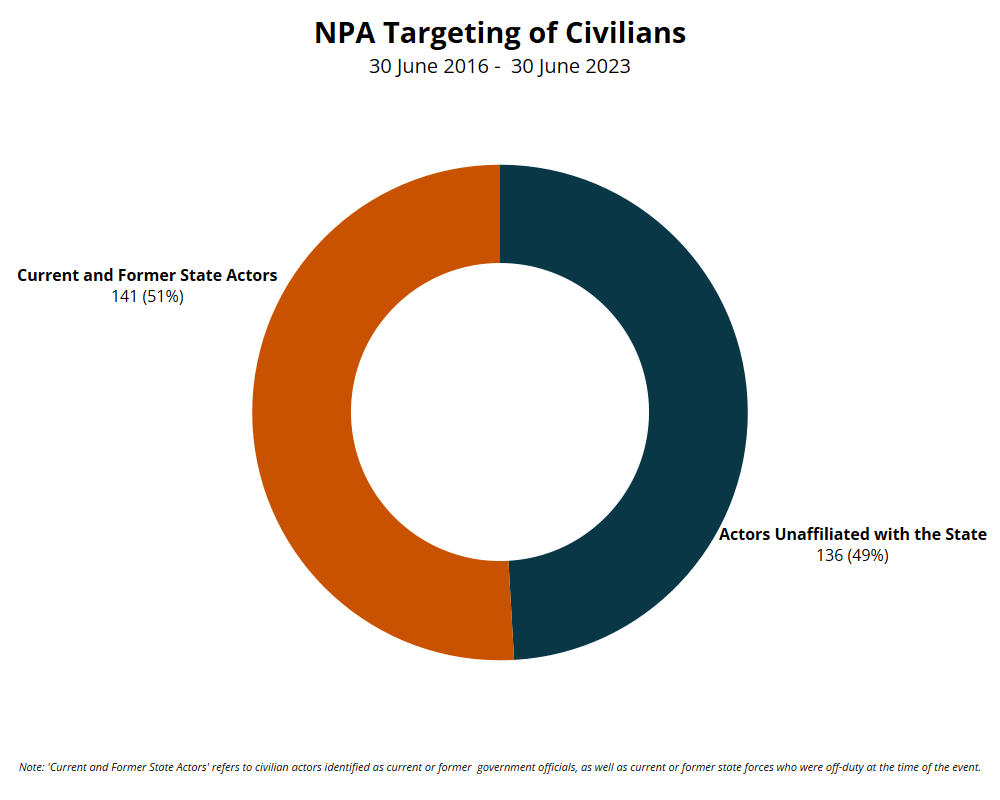

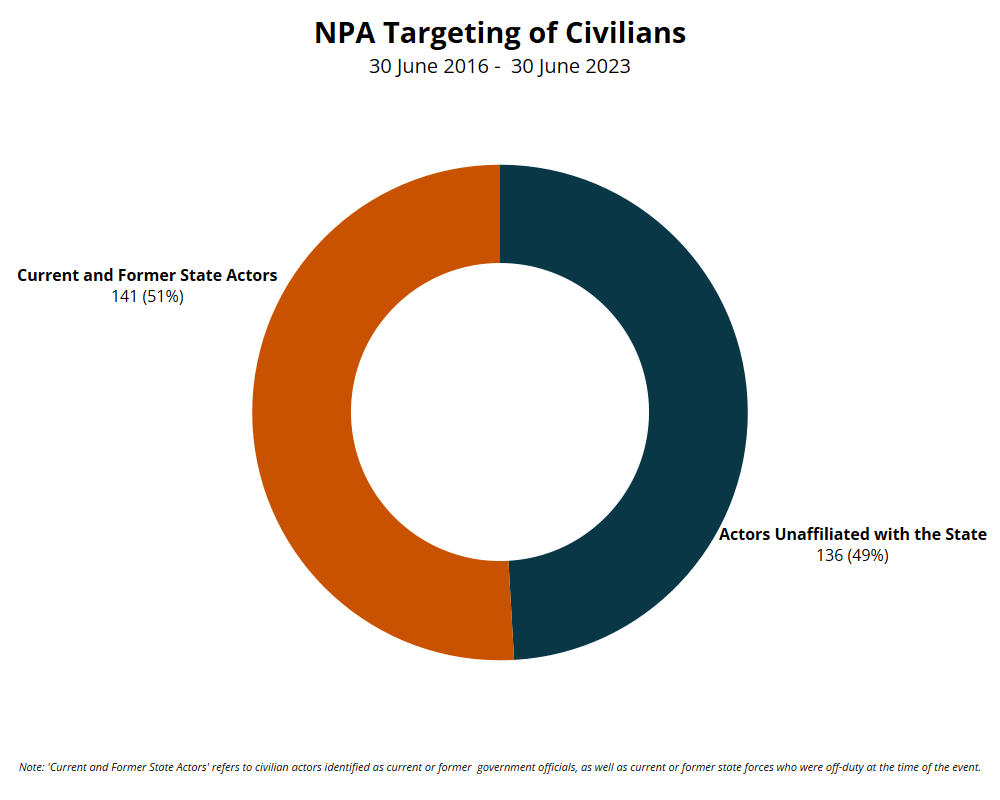

The NPA’s operations against the state go beyond armed clashes with state forces (see figure below). The rebel group also carries out ambushes and executions against individuals perceived to be state collaborators, as well as government officials and off-duty soldiers or police officers. NPA attacks against civilians, which human rights groups have condemned, are usually pronounced by the rebels as ‘revolutionary justice’ for supposed offenses against the people or the revolution. However, the ‘people’s court’ trials that make judgments “don’t meet the most basic standards of fairness,” according to Human Rights Watch.25 From the start of the Duterte regime on 30 June 2016 to 30 June 2023 under Marcos, Jr., ACLED data show over 270 events of NPA violence targeting civilians, consisting mostly of physical attacks but also including incidents of forced disappearances, sexual violence, and the use of explosives.

The CPP’s strategy of protracted people’s war stresses the peasantry’s role in providing the revolutionary army’s main force, which then aims to gradually encircle the cities from the countryside as the rebels win over rural communities. This strategy explains the NPA’s scant activity in the biggest urban centers, particularly Metropolitan Manila. Conversely, most clashes between the NPA and the military occur in remote, mountainous terrain in rural agricultural areas, particularly in the western islands of the central Philippines, and in the northern part of the main southern island of Mindanao (see map below).

ACLED data illustrate that the NPA is most active in Negros Occidental province in Western Visayas and Bukidnon province in Northern Mindanao (see inset maps above). This does not come as a surprise for a revolution with an agrarian base. Western Visayas and Northern Mindanao are both known for agrarian unrest, being two of the country’s most important agricultural centers, and therefore serve as ideal staging grounds for the CPP’s revolution. As of 2019, Western Visayas had the largest number of persons employed in agriculture in the country at 873,000, while Northern Mindanao ranked third with 776,000 persons employed in agriculture.10 Additionally, Northern Mindanao and Western Visayas rank among the top three regions in terms of their share of national agricultural production.11

Negros Occidental in Western Visayas is particularly well-known for being the bastion of sugar hacenderos, owners of thousands upon thousands of hectares of sugarcane plantations or haciendas that have provided immense wealth to the local elite since the Spanish colonial era.12 The province continues to have the most haciendas in the Philippines, despite decades of a formal government-sponsored agrarian reform program aiming to solve the problem of farmer landlessness.13 The province still dominates sugar production, accounting for 50.8% of national sugar production in 2014.14

Despite this wealth from sugar production, the province continues to be associated with profound inequality, notorious for widespread famines in the 1980s and continuing abuse, maltreatment, and even outright violence against farm workers during times of unrest.15 A characteristic example is the massacre by unidentified assailants of nine sugarcane farmers of Hacienda Nene, unemployed during the tiempo muerto (the ‘dead season’ between planting and harvesting) in Sagay in October 2018. The incident demonstrates the intersection of agrarian unrest and the communist insurgency. Security forces accused the victims of the Sagay Massacre of being NPA-affiliated provocateurs due to their participation in a bungkalan (collective cultivation work, specifically tilling, on idle lands for survival) as members of the National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW).16 Just a month later, the lawyer of the Sagay Massacre victims, also accused by authorities of being a communist, was also murdered.17

Meanwhile, Northern Mindanao also harbors its share of agrarian issues. Bukidnon, for example, is particularly well-known for its vast pineapple and banana plantations operated by leading transnational corporations such as Del Monte and Dole. However, human rights groups have sounded the alarm over abuses and attacks committed against local farmers and Indigenous peoples in the province by actors with ties to the largest agribusiness players in the region.18

These deep-seated socio-economic issues in Western Visayas and Northern Mindanao continue to persist against the backdrop of widespread poverty among agriculture workers. The latest poverty statistics in the Philippines show that farmers and fishers continue to be the poorest sectors nationally, respectively recording poverty rates of 30.0% and 30.6% in 2021,19 against the national figure of 18.1%.20

Despite the higher levels of fighting between the NPA and state forces in Western Visayas and Northern Mindanao, fighting between both sides was seen in practically all parts of the country from the start of the Duterte regime and into the Marcos, Jr. regime. This means that the NPA has been present in every region, mirroring the prevalence of agrarian issues across the country and widespread poverty of agricultural workers. Sometimes, fighting has even spilled over to the cities, with two of 33 cities classified as highly urbanized – Davao City and Butuan City in Mindanao21 – seeing considerable NPA activity. There is also elevated NPA activity in smaller regional cities, such as Himamaylan, Guihulngan, Gingoog, and Malaybalay.

The NPA’s expansive reach notwithstanding, the military and the communists publicly disagree on the strength of the NPA. In its latest anniversary statement in December 2022, the CPP claimed that the NPA had established 110 fronts across the country, while the party itself had set up committees of leadership and branches in more than 70 out of 82 provinces.22 The military, meanwhile, claimed that the number of NPA fronts is down to 22 as of December 2022.23 In May 2023, the Philippine national security adviser said that of these 22 fronts, the number of “active” guerrilla fronts had gone down to two, while 20 have been “weakened.”24

The NPA’s operations against the state go beyond armed clashes with state forces (see figure below). The rebel group also carries out ambushes and executions against individuals perceived to be state collaborators, as well as government officials and off-duty soldiers or police officers. NPA attacks against civilians, which human rights groups have condemned, are usually pronounced by the rebels as ‘revolutionary justice’ for supposed offenses against the people or the revolution. However, the ‘people’s court’ trials that make judgments “don’t meet the most basic standards of fairness,” according to Human Rights Watch.25 From the start of the Duterte regime on 30 June 2016 to 30 June 2023 under Marcos, Jr., ACLED data show over 270 events of NPA violence targeting civilians, consisting mostly of physical attacks but also including incidents of forced disappearances, sexual violence, and the use of explosives.

Duterte and the Communists: From Peace Talks to All-Out War

In June 2016, Rodrigo Duterte took office as president and promised to pursue peace with the communists. Duterte also made significant overtures to leftist social movements, appointing prominent leftist politicians to key positions in his government. Duterte’s outreach to the communists and leftist politicians reflected the good relations he had with the rebels as longtime mayor of Davao City.26 These good relations were rooted in Duterte’s involvement in leftist politics in his younger years, when he first became part of the leftist Kabataang Makabayan (Patriotic Youth) and BAYAN (New Patriotic Alliance). Duterte was also a student of Sison during his university years.27

Duterte and the CPP-NPA-NDF had initially set on reviving the dormant peace process as he was about to take power following his election in May 2016. The peace negotiations, which started on 22 August 2016 in Oslo, were initially promising. The peace negotiators reaffirmed agreements from previously aborted peace talks and started to pen further agreements on socio-economic issues.28

Coinciding with four rounds of peace talks held in Oslo, Rome, and Amsterdam, both the government and the CPP-NPA-NDF declared multiple unilateral ceasefires. The government also freed several rebel leaders so that they could participate in the peace process, most notably the husband and wife serving as the highest-ranking CPP officials, Executive Committee Chair Benito Tiamzon and Central Committee Secretary-General Wilma Tiamzon, last arrested in 2014.

However, talks broke down and the ceasefires were later terminated after the release of more political prisoners became a sticking point, with Duterte saying he conceded “too much, too soon.”29 The actual termination of the ceasefires was then followed by an intense surge in fighting (see graph below), with Duterte declaring an “all-out war” against the rebels. In February 2017, the highest level of fighting between the two sides during the Duterte regime was recorded. Duterte also ordered the rearrest of the freed rebels, many of whom had gone into hiding. Additionally, Duterte soured on the leftist politicians he had earlier appointed to his government (who were not confirmed by the Commission of Appointments), even accusing them of funneling funds to the NPA.30

Multiple attempts to salvage the talks in the following months through backchannels failed, as Duterte and Sison engaged in tirades against each other.31 Backchannel talks were canceled in July 2017 amid a surge in fighting. Duterte officially canceled the peace process in November 2017. By December 2017, Duterte signed a proclamation designating the CPP-NPA as a ‘terrorist’ group.32 A year later, in December 2018, Duterte established the NTF-ELCAC. This new body was tasked with leading a “whole-of-nation” strategy against the communist insurgency, coordinating between state forces and civilian government offices.33 Another new body, the Anti-Terrorism Council established by the controversial anti-terror law of 2020,34 gave ‘terrorist’ group designations to the CPP-NPA in December 2020,35 and to the NDF in July 2021.36 Thus, fighting continued largely unabated, with an average of nearly 22 clashes per month between state and rebel forces from February 2017, the end of the ceasefire, to June 2022, the end of Duterte’s regime.

In Duterte’s last few months in office, the military leadership said that it wished to cap the Duterte years by doing its best to quell the remaining rebels.37 Thus, the last few months of the Duterte regime saw an upward trend in fighting between the military and the NPA. This upward trend saw highs in December 2021, the 53rd anniversary month of the CPP, and in April 2022, right before the May elections.

In June 2016, Rodrigo Duterte took office as president and promised to pursue peace with the communists. Duterte also made significant overtures to leftist social movements, appointing prominent leftist politicians to key positions in his government. Duterte’s outreach to the communists and leftist politicians reflected the good relations he had with the rebels as longtime mayor of Davao City.26 These good relations were rooted in Duterte’s involvement in leftist politics in his younger years, when he first became part of the leftist Kabataang Makabayan (Patriotic Youth) and BAYAN (New Patriotic Alliance). Duterte was also a student of Sison during his university years.27

Duterte and the CPP-NPA-NDF had initially set on reviving the dormant peace process as he was about to take power following his election in May 2016. The peace negotiations, which started on 22 August 2016 in Oslo, were initially promising. The peace negotiators reaffirmed agreements from previously aborted peace talks and started to pen further agreements on socio-economic issues.28

Coinciding with four rounds of peace talks held in Oslo, Rome, and Amsterdam, both the government and the CPP-NPA-NDF declared multiple unilateral ceasefires. The government also freed several rebel leaders so that they could participate in the peace process, most notably the husband and wife serving as the highest-ranking CPP officials, Executive Committee Chair Benito Tiamzon and Central Committee Secretary-General Wilma Tiamzon, last arrested in 2014.

However, talks broke down and the ceasefires were later terminated after the release of more political prisoners became a sticking point, with Duterte saying he conceded “too much, too soon.”29 The actual termination of the ceasefires was then followed by an intense surge in fighting (see graph below), with Duterte declaring an “all-out war” against the rebels. In February 2017, the highest level of fighting between the two sides during the Duterte regime was recorded. Duterte also ordered the rearrest of the freed rebels, many of whom had gone into hiding. Additionally, Duterte soured on the leftist politicians he had earlier appointed to his government (who were not confirmed by the Commission of Appointments), even accusing them of funneling funds to the NPA.30

Multiple attempts to salvage the talks in the following months through backchannels failed, as Duterte and Sison engaged in tirades against each other.31 Backchannel talks were canceled in July 2017 amid a surge in fighting. Duterte officially canceled the peace process in November 2017. By December 2017, Duterte signed a proclamation designating the CPP-NPA as a ‘terrorist’ group.32 A year later, in December 2018, Duterte established the NTF-ELCAC. This new body was tasked with leading a “whole-of-nation” strategy against the communist insurgency, coordinating between state forces and civilian government offices.33 Another new body, the Anti-Terrorism Council established by the controversial anti-terror law of 2020,34 gave ‘terrorist’ group designations to the CPP-NPA in December 2020,35 and to the NDF in July 2021.36 Thus, fighting continued largely unabated, with an average of nearly 22 clashes per month between state and rebel forces from February 2017, the end of the ceasefire, to June 2022, the end of Duterte’s regime.

In Duterte’s last few months in office, the military leadership said that it wished to cap the Duterte years by doing its best to quell the remaining rebels.37 Thus, the last few months of the Duterte regime saw an upward trend in fighting between the military and the NPA. This upward trend saw highs in December 2021, the 53rd anniversary month of the CPP, and in April 2022, right before the May elections.

An Uncertain Path Under Marcos, Jr.

As Duterte marked his last year in office, and as the country geared up for voting in the May 2022 elections, ACLED records an uptick in violence related to the communist rebellion (see graph above). This uptick coincided with the killings or arrests of several rebel leaders, which would continue beyond the elections into the first few months of the Marcos, Jr. administration. The military also frequently reported the large-scale surrenders of rebels, though some of these surrenders were later questioned as supposedly forced or fake surrenders. In any case, these developments, alongside the death of Sison at the end of 2022, have contributed to government claims that the communist insurgency is nearly crushed.38 Accordingly, violent interactions between state forces and the NPA decreased slightly in the latter half of 2022.

The biggest blow to the NPA came on 22 August 2022 when the two highest-ranking CPP-NPA-NDF leaders, the aforementioned couple Benito Tiamzon (also known as Ka Laan) and Wilma Tiamzon (also known as Ka Bagong-tao), were reportedly killed in an explosion during a waterborne clash between the rebels and state forces. The CPP only confirmed the deaths on 20 April 2023 after a supposed months-long investigation. In the CPP’s announcement, they disputed earlier military accounts, claiming that the Tiamzons were tortured and killed on 21 August 2022, a day earlier than the military claims, before being set on a boat that exploded the next day.39

The Tiamzons’ deaths were preceded by other major losses during the Duterte regime. One of the party’s supposed intellectual stalwarts, Menandro Villanueva (also known as Ka Bok), was killed by state forces in Mindanao on 5 January 2022. Before this, the NPA’s top leader in Mindanao and nationally prominent rebel spokesperson, Jorge Madlos (also known as Ka Oris), was killed on 30 October 2021. Additionally, on 13 March 2020, state forces killed the chair of the CPP’s National Military Commission and acting chair of the CPP Politburo, Julius Giron (also known as Ka Nars).

All these losses were then capped by Sison’s death on 16 December 2022 while in exile in the Netherlands. While Sison had long been uninvolved in the day-to-day operation of the insurgency, he maintained an important role as the chief political consultant of the NDF in peace negotiations with the government, and, in general, by providing revolutionary guidance to the movement, as the CPP confirmed in tributes to Sison upon his death.40

ACLED data show a slight general downward trend in armed interactions between state forces and the NPA in the immediate months following the Tiamzons’ deaths in August 2022. Fighting was even more muted in December 2022, the month of Sison’s death, especially compared to the Decembers of previous years. Fighting normally spikes in the last month of the year as the communists mark the CPP anniversary on 26 December – though less so some years when both sides declare a Christmas ceasefire for about two weeks. However, the last time such a Christmas ceasefire was declared was in December 2019, although later both sides traded accusations of ceasefire violations.41 Since then, both sides have rejected Christmas ceasefires, and in the last few years, the lead-up to the December anniversary usually sees intensified offensives by both state forces and the NPA.

While the lower volume of fighting in the last few months of 2022 perhaps reflected the immediate aftermath of the Tiamzons’ and Sison’s deaths, possibly indicating weakened communist forces, fighting again rose in the first quarter of 2023. This upward trend reached a high in March 2023, which saw the largest number of armed interactions since December 2018. Much like in December, March sometimes sees an intensified push by both state and rebel forces, as the communist movement marks the NPA’s anniversary on 29 March. The volume of NPA activity in March 2023 suggests that the rebels might have been able to regroup and re-strategize following their losses in 2022. This latest peak in March 2023, however, was again followed by a downward trend in fighting from April to June 2023.

As things stand, the war waged by the communists in the Philippines remains the world’s longest-running communist insurgency,42 continuing to defy military pronouncements of their defeat as they have several times in the past. Nevertheless, the military asserts that the Tiamzons’ and Sison’s death has created a “leadership vacuum” that “leaves the underground movement without a sense of strategic and operational directions and the reason for its existence.”43 However, while the CPP acknowledged the “great loss” and “heavy impact” of losing the Tiamzons, Sison, and other rebel leaders, the party said that “the Central Committee and other leading organs of the Party were quickly reconstituted and revitalized.”44

As Duterte marked his last year in office, and as the country geared up for voting in the May 2022 elections, ACLED records an uptick in violence related to the communist rebellion (see graph above). This uptick coincided with the killings or arrests of several rebel leaders, which would continue beyond the elections into the first few months of the Marcos, Jr. administration. The military also frequently reported the large-scale surrenders of rebels, though some of these surrenders were later questioned as supposedly forced or fake surrenders. In any case, these developments, alongside the death of Sison at the end of 2022, have contributed to government claims that the communist insurgency is nearly crushed.38 Accordingly, violent interactions between state forces and the NPA decreased slightly in the latter half of 2022.

The biggest blow to the NPA came on 22 August 2022 when the two highest-ranking CPP-NPA-NDF leaders, the aforementioned couple Benito Tiamzon (also known as Ka Laan) and Wilma Tiamzon (also known as Ka Bagong-tao), were reportedly killed in an explosion during a waterborne clash between the rebels and state forces. The CPP only confirmed the deaths on 20 April 2023 after a supposed months-long investigation. In the CPP’s announcement, they disputed earlier military accounts, claiming that the Tiamzons were tortured and killed on 21 August 2022, a day earlier than the military claims, before being set on a boat that exploded the next day.39

The Tiamzons’ deaths were preceded by other major losses during the Duterte regime. One of the party’s supposed intellectual stalwarts, Menandro Villanueva (also known as Ka Bok), was killed by state forces in Mindanao on 5 January 2022. Before this, the NPA’s top leader in Mindanao and nationally prominent rebel spokesperson, Jorge Madlos (also known as Ka Oris), was killed on 30 October 2021. Additionally, on 13 March 2020, state forces killed the chair of the CPP’s National Military Commission and acting chair of the CPP Politburo, Julius Giron (also known as Ka Nars).

All these losses were then capped by Sison’s death on 16 December 2022 while in exile in the Netherlands. While Sison had long been uninvolved in the day-to-day operation of the insurgency, he maintained an important role as the chief political consultant of the NDF in peace negotiations with the government, and, in general, by providing revolutionary guidance to the movement, as the CPP confirmed in tributes to Sison upon his death.40

ACLED data show a slight general downward trend in armed interactions between state forces and the NPA in the immediate months following the Tiamzons’ deaths in August 2022. Fighting was even more muted in December 2022, the month of Sison’s death, especially compared to the Decembers of previous years. Fighting normally spikes in the last month of the year as the communists mark the CPP anniversary on 26 December – though less so some years when both sides declare a Christmas ceasefire for about two weeks. However, the last time such a Christmas ceasefire was declared was in December 2019, although later both sides traded accusations of ceasefire violations.41 Since then, both sides have rejected Christmas ceasefires, and in the last few years, the lead-up to the December anniversary usually sees intensified offensives by both state forces and the NPA.

While the lower volume of fighting in the last few months of 2022 perhaps reflected the immediate aftermath of the Tiamzons’ and Sison’s deaths, possibly indicating weakened communist forces, fighting again rose in the first quarter of 2023. This upward trend reached a high in March 2023, which saw the largest number of armed interactions since December 2018. Much like in December, March sometimes sees an intensified push by both state and rebel forces, as the communist movement marks the NPA’s anniversary on 29 March. The volume of NPA activity in March 2023 suggests that the rebels might have been able to regroup and re-strategize following their losses in 2022. This latest peak in March 2023, however, was again followed by a downward trend in fighting from April to June 2023.

As things stand, the war waged by the communists in the Philippines remains the world’s longest-running communist insurgency,42 continuing to defy military pronouncements of their defeat as they have several times in the past. Nevertheless, the military asserts that the Tiamzons’ and Sison’s death has created a “leadership vacuum” that “leaves the underground movement without a sense of strategic and operational directions and the reason for its existence.”43 However, while the CPP acknowledged the “great loss” and “heavy impact” of losing the Tiamzons, Sison, and other rebel leaders, the party said that “the Central Committee and other leading organs of the Party were quickly reconstituted and revitalized.”44

Red-Tagging and the Communist Insurgency

The Philippine armed forces’ campaign against the communist insurgency has been accompanied by acts of violence targeting civilians, particularly in the context of ‘red-tagging.’ Red-tagging, also sometimes referred to as red-baiting, is the practice of vilifying or labeling groups or individuals critical of the government, such as human rights defenders, labor leaders, public interest lawyers, journalists, the political opposition, religious groups, and other targeted individuals as ‘communists’ or ‘terrorists.’ In the Philippines, authorities also often conflate the terms ‘communist’ and ‘terrorist.’45

The 1957 Anti-Subversion Law, which outlawed membership in the Communist Party, was repealed in 1992 in order to legalize the party and pave the way for peace talks. Thus, mere membership in the CPP is no longer a crime, as acknowledged in 2019 by the Department of Justice.46 Nevertheless, many of those red-tagged by authorities are exposed to physical violence, with some being killed or wounded.47 In the past few years, particularly under Duterte, red-tagging has become a fraught political issue in the Philippines. In the May 2022 national elections, for example, even opposition politicians not usually identified with the main leftist formations, such as de facto leader of the opposition and then Vice President Leni Robredo of the Liberal Party, were red-tagged.48 International non-partisan organizations such as Oxfam have also not been spared.49

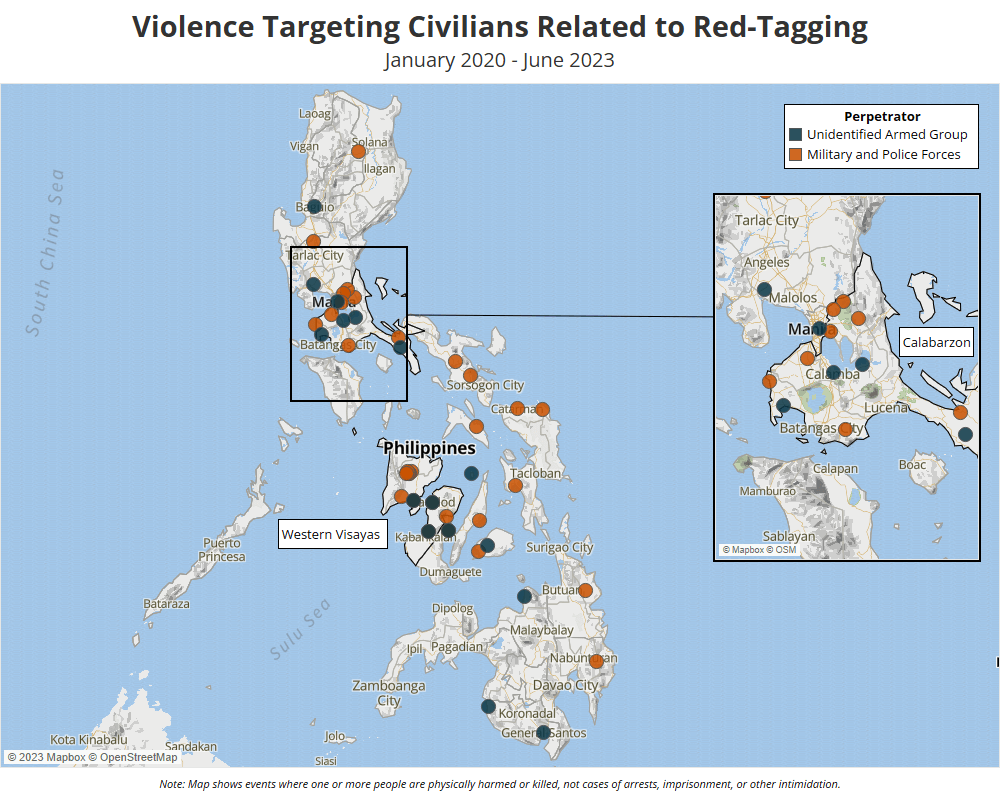

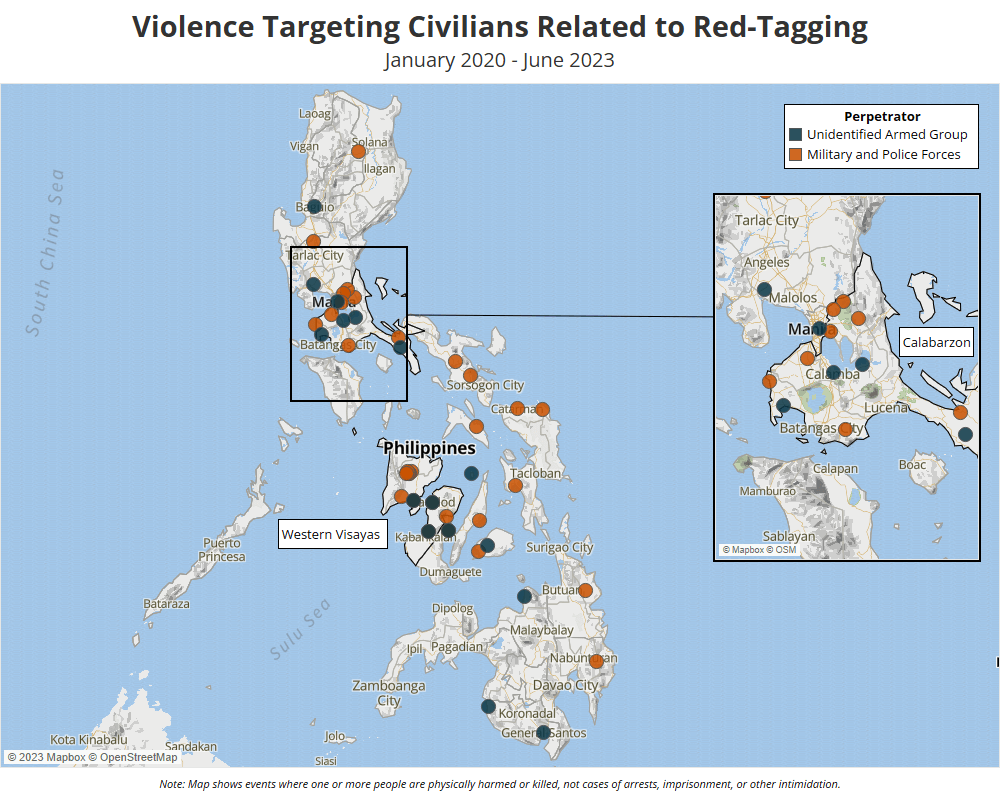

Between 2020 and 30 June 2023, ACLED records nearly 50 red-tagging related violent events targeting civilians, dispersed throughout the country (see map below). Thirteen of these events took place after Marcos, Jr. took power on 30 June 2022. These numbers include events where a person is physically harmed or killed. In line with ACLED’s methodology, this count is not inclusive of cases of arrests, imprisonment, or other intimidation, and thus offers insight into only one component of the red-tagging phenomenon.

Western Visayas and Calabarzon lead the count of violent events related to red-tagging as recorded by ACLED, with at least 12 such events each over the time period. While Western Visayas is a hotspot for agrarian unrest, as discussed above, Calabarzon, a largely urban region to the south and east of Metropolitan Manila, is also a busy area for activist organizing, especially in its significant rural pockets and industrial zones. Activists in Calabarzon faced heightened pressure from the Duterte administration in the latter part of his presidency, at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Government and military officials openly used red-tagging to suppress those organizing for labor rights amid pandemic-related hardships, as well as those opposing large-scale government projects feared to negatively impact Indigenous peoples.50

Such violence targeting civilians in Western Visayas and Calabarzon led to the two deadliest months for red-tagging-related attacks from 2020 to 2023. The deadliest month for red-tagging-related attacks was December 2020, largely due to state forces’ killing of nine red-tagged leaders of the Tumandok tribe in Capiz province in Western Visayas on 30 December, in operations that were intended to only be executions of search warrants. State forces accused tribal leaders, who belonged to a local farmer association that opposed a dam construction project in the area, of being NPA members.51 A few months later, on 3 March 2021, a lawyer representing the survivors of the attack was wounded in a stabbing attack by unidentified assailants. The lawyer had written on the issue of red-tagging as state policy, which was published around the time of his stabbing.52 This contributed to the second deadliest month for red-tagging – March 2021, which also saw what was later called in the media the ‘Bloody Sunday’ killings of 7 March, where nine local activists were reportedly killed in joint police and military operations across the Calabarzon region.53

Human rights groups have raised the issue of red-tagging numerous times. In a September 2022 report, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) said red-tagging has been linked to many reports of “killings, arbitrary detention, physical, and legal intimidation” against members of civil society, such as human rights and environmental defenders, journalists, lawyers, labor rights activists, and humanitarian workers.54 Meanwhile, in its submission to the UN Human Rights Committee in 2022, Amnesty International noted that the breakdown of peace talks between the government and the rebels in 2017 and the establishment of NTF-ELCAC in December 2018 have “led to an increase in red-tagging and security operations.”55 This coincides with the International Commission of Jurists’ observation that red-tagging was “applied with greater intensity” in President Duterte’s government.56 Amnesty International noted that red-tagging continues under the Marcos, Jr. administration, whom it asked to “end the vicious and at times deadly practice.”57 In January 2023, Human Rights Watch also raised concern about the Philippine government’s use of red-tagging to silence Indigenous opposition to projects sponsored by the government.58

Legal persecution is also a major part of the red-tagging phenomenon, with those red-tagged often subjected to dubious cases without substantial basis, or based on evidence alleged to be planted outright by state forces.59 In its 2022 year-end report, Karapatan said it had documented 4,298 illegal arrests (with or without detention) effected by state forces under Duterte from July 2016 to June 2022, and a further 197 under Marcos, Jr. from July to December 2022. Many of these arrests were described as being related to red-tagging. Karapatan also counted 591 political prisoners arrested under Duterte, and 26 under Marcos, Jr. as of December 2022.60 Public scrutiny has thus also been directed toward the Philippine justice system, with human rights groups and legal organizations expressing concern that a small number of courts have become search warrant ‘factories’ targeting red-tagged activists.61

Another manifestation of red-tagging is the allegedly forced or fake surrenders of those identified by the military as having ties to the NPA. Often, the supposed surrenders reported by the military are not of actual NPA armed combatants, but rather of those the military calls NPA ‘supporters’ or of members of activist or sectoral organizations which the military has connected to the communist insurgency. This explains why the number of surrenders reported by the military is often difficult to reconcile with the number of NPA fighters as also reported by the military. The military sometimes reports thousands of surrenders in a single region for a limited timeframe, even though the latest military estimate of the number of NPA fighters nationwide is 2,112 as of December 2022.62

The dubious surrenders thus disproportionately implicate members of red-tagged workers’ unions or farmers’ associations. Some farmers’ groups have objected to the alleged ‘fake surrenders,’ which they brand as another form of red-tagging that compels farmers to self-identify as NPA fighters against their will in highly publicized official ceremonies.63 The government’s Commission on Human Rights has launched inquiries into the supposed fake surrenders.64 Karapatan documented 3,991 “forced and fake surrenders” under the Duterte administration from July 2016 to June 2022, and 151 under the Marcos, Jr. administration from July to December 2022.65 It is worth noting that such surrenders, forced or not, carry a significant reward for the local government units involved, because barangays are incentivized when they can show that they are ‘NPA-free.’ In 2021, the NTF-ELCAC released 16.4 billion pesos (around US$324 million) to barangays that are supposedly cleared of communists, as part of the NTF-ELCAC’s Barangay Development Fund.66

The Philippine armed forces’ campaign against the communist insurgency has been accompanied by acts of violence targeting civilians, particularly in the context of ‘red-tagging.’ Red-tagging, also sometimes referred to as red-baiting, is the practice of vilifying or labeling groups or individuals critical of the government, such as human rights defenders, labor leaders, public interest lawyers, journalists, the political opposition, religious groups, and other targeted individuals as ‘communists’ or ‘terrorists.’ In the Philippines, authorities also often conflate the terms ‘communist’ and ‘terrorist.’45

The 1957 Anti-Subversion Law, which outlawed membership in the Communist Party, was repealed in 1992 in order to legalize the party and pave the way for peace talks. Thus, mere membership in the CPP is no longer a crime, as acknowledged in 2019 by the Department of Justice.46 Nevertheless, many of those red-tagged by authorities are exposed to physical violence, with some being killed or wounded.47 In the past few years, particularly under Duterte, red-tagging has become a fraught political issue in the Philippines. In the May 2022 national elections, for example, even opposition politicians not usually identified with the main leftist formations, such as de facto leader of the opposition and then Vice President Leni Robredo of the Liberal Party, were red-tagged.48 International non-partisan organizations such as Oxfam have also not been spared.49

Between 2020 and 30 June 2023, ACLED records nearly 50 red-tagging related violent events targeting civilians, dispersed throughout the country (see map below). Thirteen of these events took place after Marcos, Jr. took power on 30 June 2022. These numbers include events where a person is physically harmed or killed. In line with ACLED’s methodology, this count is not inclusive of cases of arrests, imprisonment, or other intimidation, and thus offers insight into only one component of the red-tagging phenomenon.

Western Visayas and Calabarzon lead the count of violent events related to red-tagging as recorded by ACLED, with at least 12 such events each over the time period. While Western Visayas is a hotspot for agrarian unrest, as discussed above, Calabarzon, a largely urban region to the south and east of Metropolitan Manila, is also a busy area for activist organizing, especially in its significant rural pockets and industrial zones. Activists in Calabarzon faced heightened pressure from the Duterte administration in the latter part of his presidency, at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Government and military officials openly used red-tagging to suppress those organizing for labor rights amid pandemic-related hardships, as well as those opposing large-scale government projects feared to negatively impact Indigenous peoples.50

Such violence targeting civilians in Western Visayas and Calabarzon led to the two deadliest months for red-tagging-related attacks from 2020 to 2023. The deadliest month for red-tagging-related attacks was December 2020, largely due to state forces’ killing of nine red-tagged leaders of the Tumandok tribe in Capiz province in Western Visayas on 30 December, in operations that were intended to only be executions of search warrants. State forces accused tribal leaders, who belonged to a local farmer association that opposed a dam construction project in the area, of being NPA members.51 A few months later, on 3 March 2021, a lawyer representing the survivors of the attack was wounded in a stabbing attack by unidentified assailants. The lawyer had written on the issue of red-tagging as state policy, which was published around the time of his stabbing.52 This contributed to the second deadliest month for red-tagging – March 2021, which also saw what was later called in the media the ‘Bloody Sunday’ killings of 7 March, where nine local activists were reportedly killed in joint police and military operations across the Calabarzon region.53

Human rights groups have raised the issue of red-tagging numerous times. In a September 2022 report, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) said red-tagging has been linked to many reports of “killings, arbitrary detention, physical, and legal intimidation” against members of civil society, such as human rights and environmental defenders, journalists, lawyers, labor rights activists, and humanitarian workers.54 Meanwhile, in its submission to the UN Human Rights Committee in 2022, Amnesty International noted that the breakdown of peace talks between the government and the rebels in 2017 and the establishment of NTF-ELCAC in December 2018 have “led to an increase in red-tagging and security operations.”55 This coincides with the International Commission of Jurists’ observation that red-tagging was “applied with greater intensity” in President Duterte’s government.56 Amnesty International noted that red-tagging continues under the Marcos, Jr. administration, whom it asked to “end the vicious and at times deadly practice.”57 In January 2023, Human Rights Watch also raised concern about the Philippine government’s use of red-tagging to silence Indigenous opposition to projects sponsored by the government.58

Legal persecution is also a major part of the red-tagging phenomenon, with those red-tagged often subjected to dubious cases without substantial basis, or based on evidence alleged to be planted outright by state forces.59 In its 2022 year-end report, Karapatan said it had documented 4,298 illegal arrests (with or without detention) effected by state forces under Duterte from July 2016 to June 2022, and a further 197 under Marcos, Jr. from July to December 2022. Many of these arrests were described as being related to red-tagging. Karapatan also counted 591 political prisoners arrested under Duterte, and 26 under Marcos, Jr. as of December 2022.60 Public scrutiny has thus also been directed toward the Philippine justice system, with human rights groups and legal organizations expressing concern that a small number of courts have become search warrant ‘factories’ targeting red-tagged activists.61

Another manifestation of red-tagging is the allegedly forced or fake surrenders of those identified by the military as having ties to the NPA. Often, the supposed surrenders reported by the military are not of actual NPA armed combatants, but rather of those the military calls NPA ‘supporters’ or of members of activist or sectoral organizations which the military has connected to the communist insurgency. This explains why the number of surrenders reported by the military is often difficult to reconcile with the number of NPA fighters as also reported by the military. The military sometimes reports thousands of surrenders in a single region for a limited timeframe, even though the latest military estimate of the number of NPA fighters nationwide is 2,112 as of December 2022.62

The dubious surrenders thus disproportionately implicate members of red-tagged workers’ unions or farmers’ associations. Some farmers’ groups have objected to the alleged ‘fake surrenders,’ which they brand as another form of red-tagging that compels farmers to self-identify as NPA fighters against their will in highly publicized official ceremonies.63 The government’s Commission on Human Rights has launched inquiries into the supposed fake surrenders.64 Karapatan documented 3,991 “forced and fake surrenders” under the Duterte administration from July 2016 to June 2022, and 151 under the Marcos, Jr. administration from July to December 2022.65 It is worth noting that such surrenders, forced or not, carry a significant reward for the local government units involved, because barangays are incentivized when they can show that they are ‘NPA-free.’ In 2021, the NTF-ELCAC released 16.4 billion pesos (around US$324 million) to barangays that are supposedly cleared of communists, as part of the NTF-ELCAC’s Barangay Development Fund.66

Prospects for Peace

As fighting between the government and communist rebels continues unabated, and civilians continue to be caught in the crossfire, the prospects for peace under the new Marcos, Jr. regime are dim. Formal peace talks between the government and the communist leadership, which have taken place in over 40 rounds since 1986,67 look unlikely to be revived under Marcos, Jr. This would make Marcos, Jr. the first Philippine president after the fall of his father’s dictatorship not to seek peace negotiations with the CPP-NPA-NDF.68

Marcos, Jr., however, looks keen to pursue the NTF-ELCAC’s favored style of ‘localized peace talks,’ where the government negotiates directly with individuals identified as communist rebels in local areas, rather than with the CPP-NPA-NDF leadership.69 The government has described the NTF-ELCAC’s localized peace talks as effective, saying that this approach has convinced rebels to surrender and avail themselves of government assistance.70 The government’s full backing of the NTF-ELCAC’s activities was further signaled by Marcos, Jr.’s high-profile appointment of Vice President Sara Duterte, daughter of former President Duterte, as co-chair of the anti-communist body in May 202371 – a development that has worried activist groups mindful of the vice president’s alleged history of red-tagging.72

For its part, the CPP has repeatedly rejected the NTF-ELCAC-backed localized peace talks, asserting that this approach is “a smokescreen for psychological warfare, pacification, and suppression operations” and does not address the “long-standing problems of landlessness, oppression, and exploitation.”73 Instead, the CPP continues to demand national-level peace talks. In February 2022, months before his death, Sison gave an interview as the NDF chief political consultant. In this interview, he asserted the CPP’s view that the peace talks should conform with previous agreements between the two sides and hew to the agreed agenda already set forth in the Hague Joint Declaration of 1992,74 meaning basic social, economic, political, and constitutional reforms.75 The last substantial agreement signed between the Philippine government and the communists dates back to 1998 and was the first item in the Hague Joint Declaration agenda: the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law.76 The CPP insists that the next step in the peace process should be to negotiate the Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms, followed by the Comprehensive Agreement on Political and Constitutional Reforms, and finally the Comprehensive Agreement for the End of Hostilities and Disposition of Forces.77 By the latter half of Duterte’s term, however, the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process had begun to question the constitutionality of the previous agreements between the government and the NDF.78

The fate of the communist insurgency under the Marcos, Jr. presidency is of particular interest given the long history between the Marcos family and the communists. The elder Marcos often invoked the threat of communist rebellion for the severe military measures he implemented during his dictatorship, particularly when he placed the country under martial law.79 The younger Marcos would repeat this claim in 2022 to defend his father’s strongman rule.80 However, such military measures greatly contributed to the widespread violation of human rights under the Marcos dictatorship.

In 2022, amid the younger Marcos’s rise to power, Amnesty International warned against a “disturbing revisionist narrative” that minimized the human rights abuses under the elder Marcos as a necessary response to the communist threat. Against this narrative, the human rights group reminded the public that it had documented “tens of thousands of people arbitrarily arrested and detained, and thousands of others tortured, forcibly disappeared, and killed” during Marcos, Sr.’s dictatorship, targeting individuals “critical of the government or perceived as political opponents.”81 The government’s very own Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission, established by law in 2013 to provide for state reparations for abuses under the Marcos, Sr. regime, also lists 11,103 officially recognized victims of human rights violations under Marcos’s martial law to date.82 The revisionist narrative, which obscured these facts and enabled the political rehabilitation of the Marcos family, plays into the hands of those in the present security establishment who wish to return to martial law-era approaches to peace and order. The CPP-NPA-NDF’s existence is thus invoked anew as justification for red-tagging and other human rights abuses.

Now, with Marcos, Jr.’s campaign against the communist insurgency bolstered by the vast powers of the Duterte-era NTF-ELCAC, and with the communist insurgency vowing to march on despite recent setbacks, the two sides look further than ever from a peaceful resolution.

[Visuals in this report were produced by Christian Jaffe]

As fighting between the government and communist rebels continues unabated, and civilians continue to be caught in the crossfire, the prospects for peace under the new Marcos, Jr. regime are dim. Formal peace talks between the government and the communist leadership, which have taken place in over 40 rounds since 1986,67 look unlikely to be revived under Marcos, Jr. This would make Marcos, Jr. the first Philippine president after the fall of his father’s dictatorship not to seek peace negotiations with the CPP-NPA-NDF.68

Marcos, Jr., however, looks keen to pursue the NTF-ELCAC’s favored style of ‘localized peace talks,’ where the government negotiates directly with individuals identified as communist rebels in local areas, rather than with the CPP-NPA-NDF leadership.69 The government has described the NTF-ELCAC’s localized peace talks as effective, saying that this approach has convinced rebels to surrender and avail themselves of government assistance.70 The government’s full backing of the NTF-ELCAC’s activities was further signaled by Marcos, Jr.’s high-profile appointment of Vice President Sara Duterte, daughter of former President Duterte, as co-chair of the anti-communist body in May 202371 – a development that has worried activist groups mindful of the vice president’s alleged history of red-tagging.72

For its part, the CPP has repeatedly rejected the NTF-ELCAC-backed localized peace talks, asserting that this approach is “a smokescreen for psychological warfare, pacification, and suppression operations” and does not address the “long-standing problems of landlessness, oppression, and exploitation.”73 Instead, the CPP continues to demand national-level peace talks. In February 2022, months before his death, Sison gave an interview as the NDF chief political consultant. In this interview, he asserted the CPP’s view that the peace talks should conform with previous agreements between the two sides and hew to the agreed agenda already set forth in the Hague Joint Declaration of 1992,74 meaning basic social, economic, political, and constitutional reforms.75 The last substantial agreement signed between the Philippine government and the communists dates back to 1998 and was the first item in the Hague Joint Declaration agenda: the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law.76 The CPP insists that the next step in the peace process should be to negotiate the Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms, followed by the Comprehensive Agreement on Political and Constitutional Reforms, and finally the Comprehensive Agreement for the End of Hostilities and Disposition of Forces.77 By the latter half of Duterte’s term, however, the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process had begun to question the constitutionality of the previous agreements between the government and the NDF.78

The fate of the communist insurgency under the Marcos, Jr. presidency is of particular interest given the long history between the Marcos family and the communists. The elder Marcos often invoked the threat of communist rebellion for the severe military measures he implemented during his dictatorship, particularly when he placed the country under martial law.79 The younger Marcos would repeat this claim in 2022 to defend his father’s strongman rule.80 However, such military measures greatly contributed to the widespread violation of human rights under the Marcos dictatorship.

In 2022, amid the younger Marcos’s rise to power, Amnesty International warned against a “disturbing revisionist narrative” that minimized the human rights abuses under the elder Marcos as a necessary response to the communist threat. Against this narrative, the human rights group reminded the public that it had documented “tens of thousands of people arbitrarily arrested and detained, and thousands of others tortured, forcibly disappeared, and killed” during Marcos, Sr.’s dictatorship, targeting individuals “critical of the government or perceived as political opponents.”81 The government’s very own Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission, established by law in 2013 to provide for state reparations for abuses under the Marcos, Sr. regime, also lists 11,103 officially recognized victims of human rights violations under Marcos’s martial law to date.82 The revisionist narrative, which obscured these facts and enabled the political rehabilitation of the Marcos family, plays into the hands of those in the present security establishment who wish to return to martial law-era approaches to peace and order. The CPP-NPA-NDF’s existence is thus invoked anew as justification for red-tagging and other human rights abuses.

Now, with Marcos, Jr.’s campaign against the communist insurgency bolstered by the vast powers of the Duterte-era NTF-ELCAC, and with the communist insurgency vowing to march on despite recent setbacks, the two sides look further than ever from a peaceful resolution.

[Visuals in this report were produced by Christian Jaffe]

[For more information about ACLED go to the following URL: https://acleddata.com/about-acled/

https://acleddata.com/2023/07/13/the-communist-insurgency-in-the-philippines-a-protracted-peoples-war-continues/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.