The USS John C. Stennis has sailed through the disputed South China Sea to demonstrate America's interest in the region. SEAMAN TOMAS COMPIAN

In late August, the U.S. Department of Defense released a statement criticizing military exercises of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) in the South China Sea.

In particular, the U.S. objected to the firing of ballistic missiles (DF-26B and DF-21D), which "further destabilize the situation in the South China Sea".

The DF-26 has a range of 4,000 kilometres and can be used in nuclear or conventional strikes against ground and naval targets. The DF-21 has a range of about 1,800 kilometres.

It's been reported that before the Pentagon criticized the PLA exercises, U.S. reconnaissance planes flew over the South China Sea.

In addition, it guided-missile destroyer, USS Mustin, trespassed into Chinese-claimed territorial waters off the Xisha Islands in late May, according to a Chinese People's Liberation Army spokeperson.

The U.S. has declared China's territorial claims "illegal". It wants its "bullied" neighbours to stand their ground.

"We are making clear: Beijing's claims to offshore resources across most of the South China Sea are completely unlawful," Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in a statement on July 13.

The current escalations raise questions, such as: is a clash within the South China Sea now unavoidable? Do the disputes in the South China Sea have the potential to explode a regional conflict? Before we dig deeper into these questions, let us take a cursory look into history.

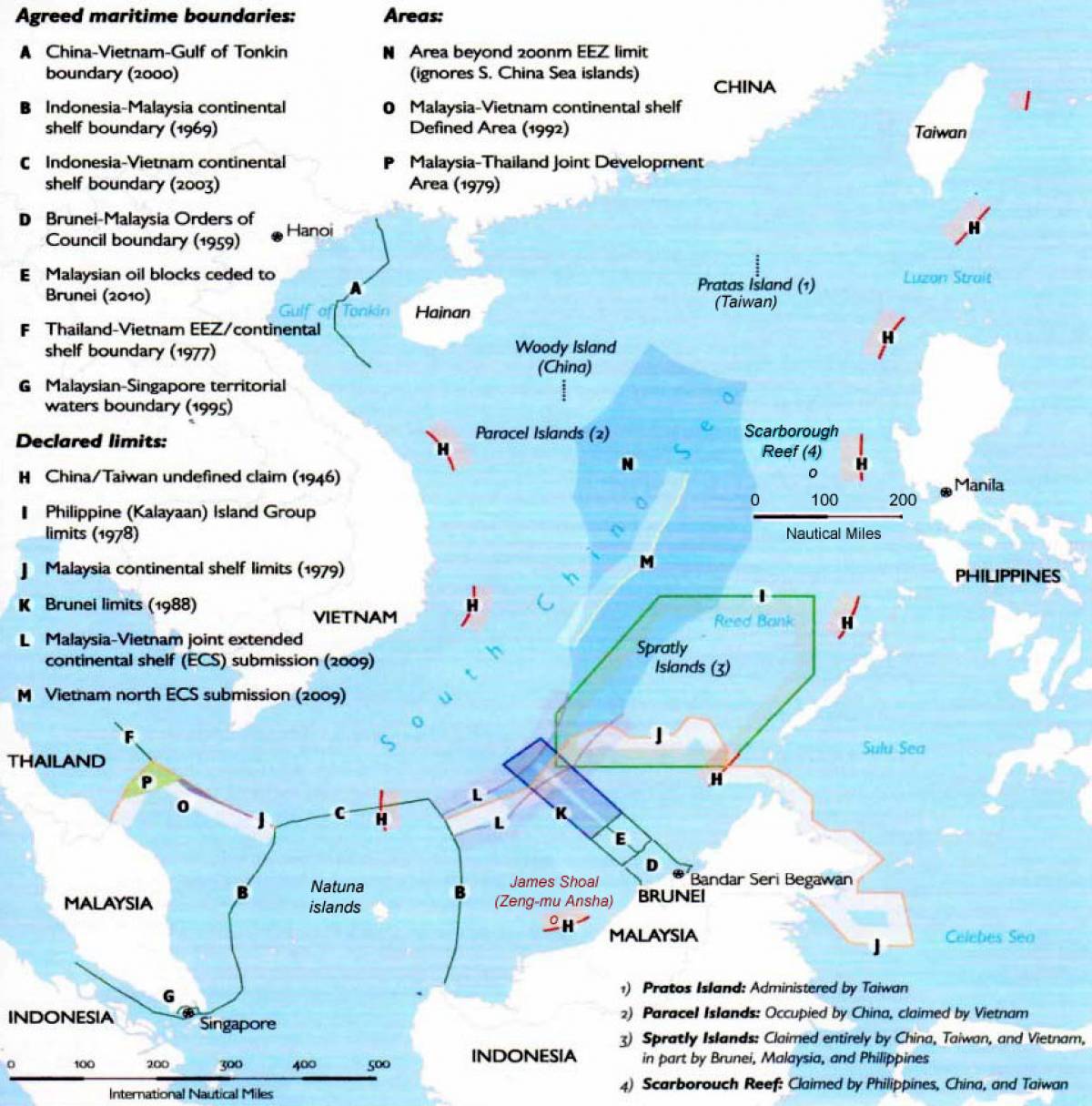

This U.S. Department of Defense map shows how complicated issues have become in the South China Sea.

History of South China Sea claims

History of South China Sea claims

One of the world's busiest waterways, the South China Sea is subject to several overlapping territorial disputes involving China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei.

The conflict has remained unresolved for decades, but has more recently emerged as a flashpoint in China-U.S. relations in Asia.

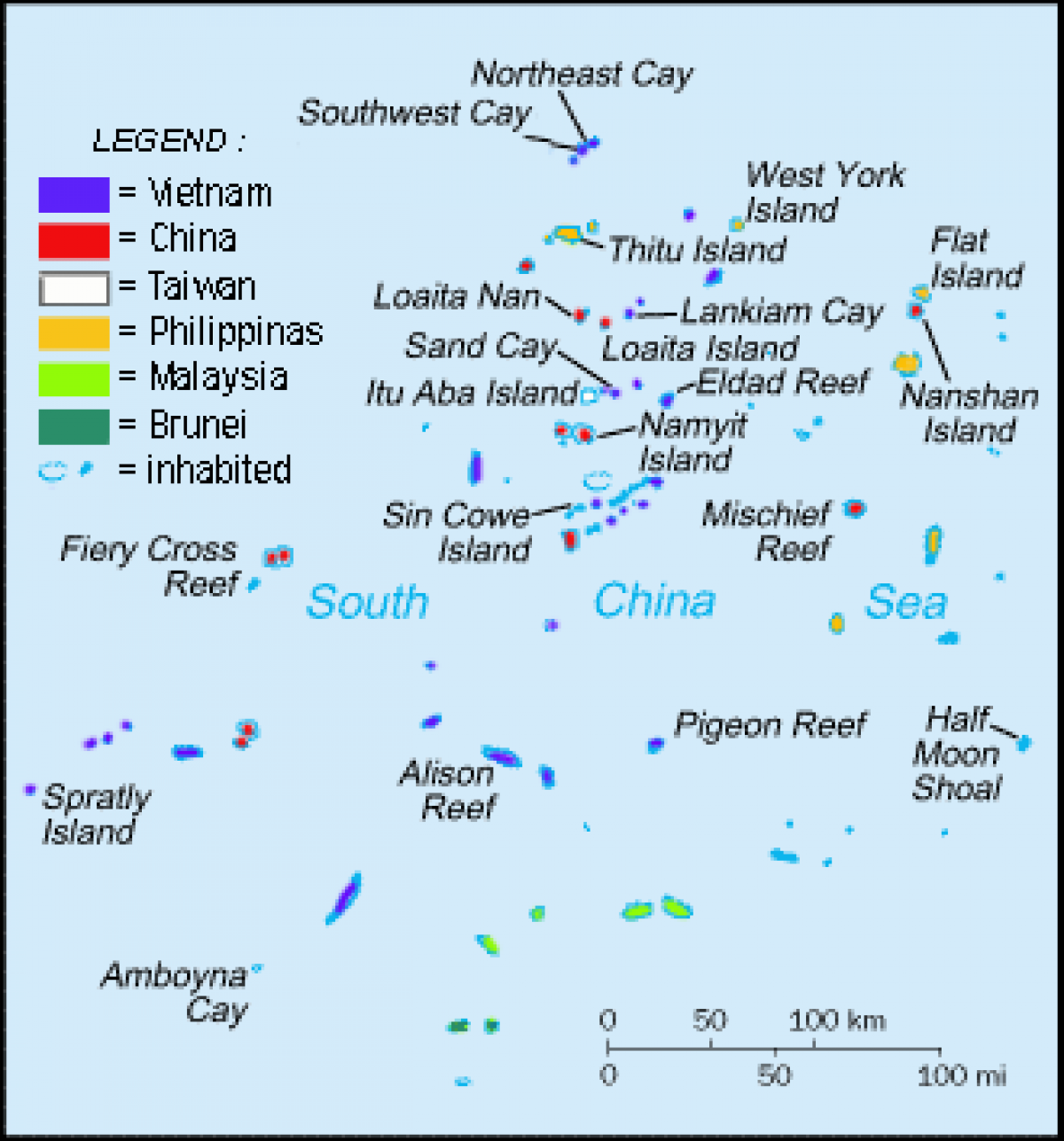

The Philippines, Vietnam, China, Brunei, Taiwan, and Malaysia hold different, sometimes overlapping, territorial claims over the sea, based on various historical and geographic accounts. China claims more than 80 percent, while Vietnam claims sovereignty over the Paracel Islands and the Spratly Islands.

At the end of the Second World War, no claimant occupied a single island in the entire South China Sea. Then in 1946, China established itself on a few features in the Spratlys.

In early 1947, it also snapped up Woody Island, part of the Paracel Islands chain, only two weeks before the French and Vietnamese intended to make landfall.

Denied their first pick, the French and Vietnamese settled for the nearby Pattle Island.

In 1955 and 1956, China and Taiwan established permanent presences on several key islands, while a Philippine citizen, Thomas Cloma, claimed much of the Spratly Islands chain as his own.

By the early 1970s, issues relating to claims were raised again after oil was discovered beneath the South China Sea waters. The Philippines was the first to move. China followed shortly after that with a carefully coordinated seaborne invasion of several islands.

In the Battle of the Paracel Islands, it wrested several sites from South Vietnam's control, killing several dozen Vietnamese and sinking a corvette warship in the process. In response, both South and North Vietnam reinforced their remaining garrisons and seized several other unoccupied sites.

In 1988, China moved into the Spratlys and set off another round of occupations by the claimants. Tensions crested when Beijing forcibly occupied Johnson South Reef, killing several dozen Vietnamese sailors in the process.

In 2002, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China came together to sign the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea. The declaration sought to establish a framework for the eventual negotiation of a Code of Conduct for the South China Sea.

The parties promised "to exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability".

In May 2009, Malaysia and Vietnam sent a joint submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, setting out some of their claims. This initial submission unleashed a flurry of notes verbales from other claimants, who objected to the two nation’s claims.

In particular, China responded to the joint submission by submitting a “nine-dash line" map. This line moves around the South China Sea edges and encompasses all of the sea's territorial features and the vast majority of its waters.

On January 22, 2013, the Philippines filed an arbitration case against China, under the auspices of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Although China asserts that this cannot be resolved without deciding territorial issues first, the Philippines claims centre around maritime law issues.

For that reason, Beijing has mostly refused to participate in the proceedings, although it has drafted and publicly released a position paper opposing the tribunal's jurisdiction.

The Philippines submitted its "memorial" and a response to China's position paper. In 2016, the tribunal largely ruled in favour of the Philippines, concluding that China’s claim regarding its nine-dash line was invalid.

Trade and economic significance of South China Sea

The South China Sea is a very important commercial waterway connecting Asia with Europe and Africa, and its seabed is rich with natural resources. One-third of global shipping, or a total of US$3.37 trillion of international trade, passes through the South China Sea.

About 80 percent of China's oil imports arrive via the Strait of Malacca, in Indonesia. They then sail across the South China Sea to reach China.

The sea is also believed to contain significant natural resources, such as natural gas and oil. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates that the area has at least 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. Other estimates are as high as 22 billion barrels of oil and 290 trillion cubic feet of gas.

The South China Sea also accounts for 10 percent of the world's fisheries, making it a critical food source for hundreds of millions of people.

This map shows some of the overlapping claims over the Spratly Islands.

Perspective

Perspective

One can wonder why the U.S., which has no border with the South China Sea, is so concerned about the South China Sea. Seattle, a major city of Washington state, is about 22,458 kilometres away.

Are China and the U.S. on the verge of war?

One can also raise another important question: when China and the U.S. are economically interdependent and share common economic goals, development models, and interests, why is this confrontation taking place?

Let us try to find some logical answers to these questions.

According to various reports, the U.S. has wide-ranging security commitments in East Asia and is allied with several countries bordering the South China Sea, such as the Philippines.

Furthermore, the South China Sea is a vital trade route in the global supply chain, used by American companies that produce goods in the region.

It's also been reported that although the U.S. does not officially align with any of the claimants, it has conducted Freedom of Navigation operations. These are designed to challenge what Washington considers excessive claims and to ensure the free passage of commercial ships in these waters.

China is a fast-emerging global superpower in technology and the development of military arsenal, with a strong GDP and a strong hidden desire to attain the status of an empire.

History indicates that other than the military muscle and technology, control over trade routes is a fundamental footstep on the road to achieving this goal.

China has developed bases in the South China Sea. It also owns the Djibouti and Gwadar ports and created the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a parallel to European and U.S. aid-giving agencies.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a multibillion Chinese project, is central to the control over trade routes.

The U.S. and other western countries believe that the Chinese are militarizing the BRI.

In an article entitled “The Coming Post-COVID Anarchy", published in Foreign Affairs on May 6, former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd maintains that a decision in Beijing to militarize the BRI would increasingly raise the risk of proxy wars.

Further, Rudd suggests that the U.S. and China adopt better policies to avoid a confrontation. He also mentions in his article that “History is not predetermined."

That is very right. History proceeds because of the contradictions generated, and not simply because of U.S. or Chinese policy.

State-controlled capitalism versus liberal capitalism

Let us dig deeper to explore the root cause of the U.S.–China conflict.

The study of history tells us that there are many conflicts that arise during the development and existence of things.

Essentially, the principal conflict—its existence and development—determine or influence the other conflicts' existence and development.

There is only one main conflict that plays the leading role at every stage in the development of a process.

To understand the nature of the main conflict, one needs to study history since 1917. At that point, the world was divided between two ideologies, capitalism and socialism.

That division constituted the "main conflict" in those times.

After the fall of socialism in the USSR and China, the nature of the main conflict changed. Russia and China started following the capitalist road.

Now, the conflict is between forms of capitalism, i.e., liberal capitalism (the U.S. and the West) and state-controlled capitalism (Russia and China).

The contending powers are not struggling over ideology but are working to capture the market economy's significant share.

The contending powers are using one another and collaborating. We could even say the opponents cannot live without each other yet want to kill each other.

The South China Sea conflict is one manifestation of the main conflict.

The other pertinent question could be: will the U.S. alone fight China or try to create a regional bloc to fight China?

It appears as though the South China Sea conflict is acting as a pole around which regional blocs are emerging.

The U.S., with Australia and India, are rallying against China in the South China Sea waters. All these countries do not have any territorial claims in the South China sea.

In comparison to China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Taiwan, and Malaysia are small countries. They may not take an independent stance or any action against an emerging superpower like China on their own.

However, U.S. support and assurances to these small countries could lead to a larger regional bloc against China.

Recent developments indicate that the Philippines, which filed the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea complaint against China, is now not on the forefront against China. Instead, it seems to be demonstrating noncommittal or vacillating behaviour.

Smaller countries become very fragile when they fall between a conflict among big powers. Generally, smaller nations follow those with more leverage in terms of their economic dependence and social clout within their countries.

Historically, the U.S. and the West have had far more influence in these smaller countries in comparison to China.

This dependence of the smaller regional countries could potentially push them to join the U.S. bloc against China, which very well might result in proxy wars against China.

[Khalid Zaka is a social justice advocate living in Surrey, British Columbia. The Georgia Straight publishes opinions like this from the community to encourage constructive debate on important issues.]

https://www.straight.com/news/khalid-zaka-a-summary-of-south-china-sea-conflict

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.