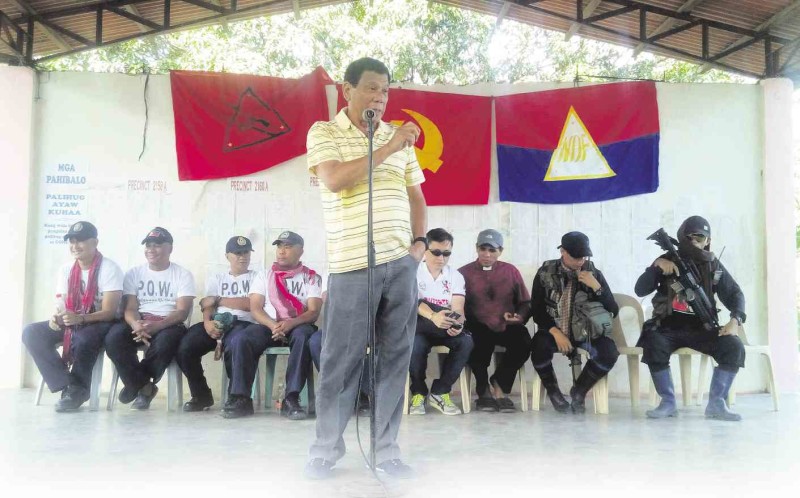

RELEASE OF POWS Five police officers captured by the New People’s Army in Paquibato, Davao City on April 16 were turned over to Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte on April 25 on orders of the communist-led National Democratic Front. BARRY HAYLAN/CONTRIBUTOR

It is likely that the less trumpeted yet long-awaited peace agreement between the Philippine government (GPH) and the National Democratic Front (NDF) may be achieved by the next administration sooner than we all expected.

Yet, forging an agreement and making an agreement stick are two separate challenges, of which the latter is doubly difficult.

A durable agreement will require an outcome that is inclusive and a process that employs out-of-the-box approaches and solutions distinct from previous peace negotiations with both the NDF and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

Genuine change

The resumption of the peace process started even before the new administration was sworn in. The incoming President Rodrigo Duterte started the process when he announced that he would bring home at the soonest possible time his former instructor and chief NDF peace consultant Jose Maria Sison.

The latter quickly secured a face-to-face meeting with the incoming President, albeit through Skype in contrast to the meeting between President Aquino and MILF Chair Murad Ebrahim in Tokyo.

Duterte likewise announced that he was open to a ceasefire and the release of all political prisoners to enable their direct participation in the negotiations. Finally, a bewildered NDF was offered important government positions even before it asked for any post, casting the public imagery of a de-facto coalition government.

All of these happened within the first two weeks following the 2016 elections.

These announcements are certainly unprecedented. Forget for a moment the contested Cabinet announcements and ignore the verbal clashes with the Church and other business groups. In contrast, the offers made are so daring and counterintuitive that it successfully conveyed the first real signs of change that all presidential candidates promised in the 2016 campaign.

Here was the olive branch being offered to the NDF devoid of the usual anticommunist rhetoric and the call to surrender, and free from the worn-out “talk-and-fight” parameters of the past that prevented the achievement of a durable peace.

Trust iron-clad

Trust is a critical ingredient and previous negotiations collapsed because of the lack of it. To bring about a final agreement, an even higher level of confidence and trust is required to break the impasse and speed up the process.

In this case, the enormous social capital between Duterte and the CPP-NPA-NDF (CNN) will certainly be an important and crucial factor. It is widely known that Duterte established a peaceful and stable arrangement with insurgents in his own backyard since 1986. His ability to secure a local political settlement led to an arrangement that helped turn Davao City into a haven for peace, security and development.

Additionally, Duterte possesses the status and confidence that many in the insurgent hierarchy, including the rebel-commanders on the ground, recognize and respect. This empathy is unmatched by any local or national government official in the country today and it will be an important ingredient in ensuring wider flexibility, an openness to criticism and a willingness to try out new approaches without motives being questioned.

Inclusiveness

However, trust is only one aspect, inclusiveness is another. Mr. Aquino enjoyed the same level of trust with the MILF that turned out to be insufficient in securing the Bangsamoro Basic Law. Indeed, a surfeit of trust can also lead to tunnel vision and a tayo-tayo mentality that excludes others.

A peace agreement that excludes powerful segments in society can actually reinforce rather than reduce violence. Worse, it can jeopardize lives on both sides of the conflict and can cause the country to slide back into a state of revenge and retribution or a more intense civil war than we face at the moment.

A robust and inclusive process is necessary at the outset to secure the widest possible buy-in from strategic stakeholders in society. However, inclusiveness here does not only refer to the grassroots and participatory framework that pervades NGO-speak.

The inclusive approach instead means that those who wield power and are vital in cloaking a peace agreement with legitimacy and authority must be brought into the negotiations at the first instance. The strategic role of economic and political elites is emphasized here not because the poor are unimportant, but rather because only the former possess the resources and political clout to make or break an agreement and undermine the state.

Political settlements

It is necessary to turn the current negotiations into a genuine political settlement that shapes how the central state deals with polarization, dissent and violent challenges to its rule. A genuine settlement needs to rally the elites around a political bargain that reduces their uncertainty and fears, and mobilizes their contribution to consolidating the peace and pursuing development in conflict-affected areas.

Doing so requires politicians from both houses of Congress to be brought in at the outset. Regular consultations with members of the Supreme Court is a must. Big business and the private sector must be harnessed to inform the negotiations and underwrite the costs of an agreement, and to eventually provide the sort of jobs to former combatants that will not require them to ever hold guns again.

Enabling environment

An enabling environment must also be created based on honest and credible commitments and the willingness to accept the risks that abound on both sides of this conflict. All peace processes run the risk of diluting the power and authority of both sides over their respective constituents. In these instances, credible commitments mean that each side should be prepared to cover the other’s back.

The immediate reconstitution of the Joint Agreement on Security and Immunity Guarantees (Jasig) is central to testing this commitment to each other.

In the previous round of negotiations, the work of the peace panels was dislocated by the arrest of CNN personalities and the refusal to release these personalities because of the so-called inability to verify the identities of NDF staff and consultants. This could have been resolved easily by reconstituting the Jasig list and embedding a better system for identity verification.

Instead, the impasse from the Jasig contaminated the rest of the talks, including prior agreements reached with previous administrations, such as The Hague Joint Declaration. Yet, how could we honestly expect a free discussion and a secure and unhampered process when the partner across the table cannot be assured of their physical safety?

An enabling environment must, therefore, include a provision for prisoner releases, whether wholesale or partial and calibrated, and the requirement that released prisoners directly participate in the GPH-NDF peace process.

It further includes directing government prosecutors to stop the filing of criminal cases for political and rebellion-related offenses, to swiftly release prisoners as ordered by the courts and to back-pedal on outstanding criminal cases already filed—an incentive that whistle-blowers often get.

Finally, creating an enabling environment must include the herculean effort to undertake a constitutional reform process that marches in step with the peace processes. Charter change provides an important platform and a marketplace of ideas where delicate and unresolved subjects in the negotiations can be thrown into the wider public debate and consensus-building process.

Tangible outcomes

Back-channel processes often precede formal discussions to speed up the process and facilitate a settlement. Both tracks must move in parallel and actors need to move quickly and decisively to prevent spoilers from consolidating an effective and vigorous opposition to any agreement.

In this regard, the simultaneous, rather than sequential, working of all the relevant panels on social and economic reforms (Caser), political and constitutional reforms (PCR), and the end of hostilities and disposition of forces (EH-DOF) is important.

The search for safe spaces here and abroad and a more active engagement with the Norwegian third-party facilitator, including allowing the NDF to harness as many consultants and staff as possible will help to turn the process into an effective mass movement for peace.

To cease fire or not

Studies on conflict suggest that working toward scheduled or indefinite ceasefires can deflect the attention of the panels from the root causes of the conflict and exhaust the available goodwill even before the substantive issues are addressed. This is an important lesson in peace negotiations and must not be taken lightly.

However, working on the root causes should not delay the delivery of immediate economic and political benefits to those yearning for an end to violence and instability in their lives. This is also crucial if one endeavors a wider constituency for the peace process itself.

A central issue here is an agreement for an indefinite ceasefire that can help get the wider public engaged in the process. The ceasefire continues to hold in the case of the MILF and several agreements were smoothly achieved because of the cessation of hostilities. In Colombia, no ceasefire was called but an agreement to suspend narcotics production and decelerate the drug trade, including forced payoffs from businesses while talks were ongoing, was also part of the discussions.

Human, economic costs

Both sides need to be aware and must regularly monitor the human and economic costs of the conflict. Efforts must be made to frequently communicate the rising costs of violence brought about by constant delays in achieving a settlement.

In the southern region of Mindanao alone where the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the New People’s Army (NPA) are at loggerheads, per-capita and per-kilometer conflict incidence plus the total human costs in terms of deaths, injuries and displacement are more than double those registered in the five provinces of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, according to the Mindanao conflict databases of International Alert UK.

The lack of knowledge about the scale and magnitude of violent conflict partly explains why a narrow constituency exists for the GPH-NDF process in contrast to the GPH-MILF process. Media often focus on sensational crimes and violent extremism, suggesting that peace building to address the rebellion in Muslim Mindanao is the only determinant for securing a lasting peace in the South.

Getting reliable information on violent conflict is also crucial in dealing with issues of transitional justice after a settlement is secured.

Managing expectations

“It is going to get worse before it gets better” is a mantra often used to manage expectations and to avoid an even more bloody outcome arising from any setback in a peace negotiation. This is dramatized by the intensifying bloodshed arising from the two-sided campaigns to win the hearts and minds of the lumad in the latter part of 2015 when both the formal and informal talks were ended.

This must be taken to heart because it underscores the essentially fragile nature of peace processes in which the fate of the whole nation is placed in the hands of a few negotiators and their principals.

We only need to look back at the experience of the GPH-MILF peace panels following the Mamasapano tragedy to realize the fragility of political settlements—whether these have been institutionalized into law.

Hate language

Worse, a failed experiment that raises the highest expectations normally leads to bloodier outcomes and deeper cleavages in society as evidenced in the conflict-insensitive and hate language that greeted Muslims following the incident.

Indeed, the contagion effects of a failed process is clearly evident in the Mamasapano case when the GPH-NDF peace process became one of the costliest yet unrecognized casualties of the bloodshed.

Communications work is central to avoiding the same pitfalls and perils in the case of the GPH-NDF peace process. Communication offensives in the mainstream and social media must be undertaken to ensure that expectations are more sensitive and realistic.

Already, the intramurals in this peace process are being covered extensively in the media, with both sides communicating directly with each other. This is a good start and a welcome development.

However, when the President is sworn in, Congress is convened, the first formal negotiation is undertaken and the early days are over, both panels must start communicating with the broader society as well.

Save children from war

Most of us have probably given up on the thought that the communist insurgency would end in a lasting peace during our lifetime.

The British-American political activist and revolutionary Thomas Paine once remarked that he would rather deal with violent conflict himself in his time, rather than to have his children inherit war and live with it. “I prefer peace. But if trouble must come, let it come in my time, so that my children can live in peace.”

This rather hopeful yet pessimistic account of a lasting peace was shattered in the past two weeks. We can still win the peace in our lifetime. We just need to work harder for it.

(Francisco “Pancho” Lara Jr. is country manager of International Alert UK in the Philippines. He holds an undergraduate degree from the University of the Philippines Diliman, and both MSc and Ph.D. degrees from the London School of Economics.)

http://opinion.inquirer.net/94953/securing-peace-in-our-lifetime

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.