A spate of shipjackings and kidnapping-for-ransoms has imperiled regional trade in Southeast Asia and prompted calls for trilateral maritime policing in the waters between the

The Context

Starting on 26 March 2016, militants from the Abu Sayyaf

Group (ASG) began a spate of maritime

kidnappings. Three Indonesian vessels and a Malaysian tugboat were

hijacked, and some 18 sailors were taken hostage.

A screen capture from Abu Sayyaf’s fifth video of Norwegian,

Kjartan Sekkingstad (l), and Canadian, Robert Hall (r), released on 14 May 2016

Their treatment was very different than the three Western

hostages abducted from a Davao

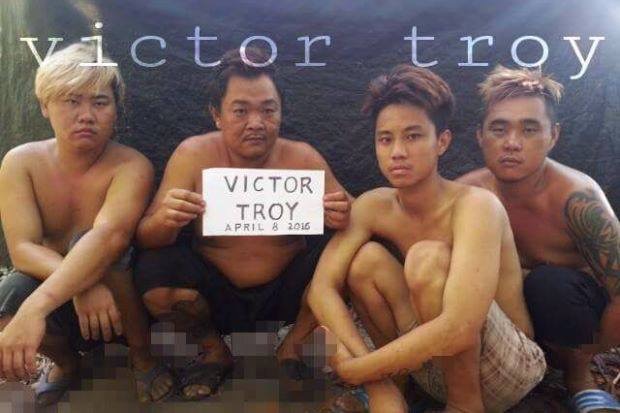

Photograph of the four Malaysian sailors, released via

Facebook, on 15 April 2016

The Malaysian and Indonesian sailors, by contrast, were

quickly put in contact with their families and companies to arrange ransom

payments. Although the ASG threatened to behead the four Malaysian sailors if no

ransom was paid, there was no IS imagery in the photo posted on Facebook in

the proof of life picture that the ASG released. In all three cases,

ransoms were paid and the suspects released. Various press reports indicate

that the four Malaysians were released with the payment of 140

million pesos ($2.97 million), while ten Indonesians were

released following a 50

million pesos ($1.06 million) ransom, and the final four released with

a 15

million pesos ($319,000) ransom. The payment of ransoms was always

officially denied.

While governments may have not paid the ransom, family members, shipping firms,

friends, and insurance companies appear to have come up with the requisite

funds. Malaysian Home Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi acknowledged that money changed

hands, but “channeled not as ransom, but to a body in the Philippines

Not surprisingly, with the payment of large ransoms,

shipjackings/kidnappings have continued. On 20 June another Indonesian

tugboat was boarded and seven of its thirteen crew members taken hostage.

Though the remaining six were able to steer the ship to a safe port, the ASG

is demanding $4.8

million in ransom for the release of the seven. Within days of

the hijacking the captain was able to call

his wife and convey the ransom demand.

The Costs

These shipjackings/maritime kidnappings imperil regional

trade. While only a small amount of the $40

billion in regional maritime trade passes through these waters, it

is not insignificant. Indonesian coal exports from East

Kalimantan account for 70 percent of total Philippine coal

imports, worth over $800

million. There are an estimated 55

million metric tons of goods that transit these waters

annually. These exports are all the more important as Chinese imports of raw

materials from Southeast Asia continue to fall with China Philippines Philippines

from Indonesian ports, “The moratorium on coal exports to the Philippines will be extended until there is a

guarantee for security from the Philippines

Calls for Trilateral Maritime Policing

For the first time in many years, Malaysian and Indonesian

leaders have been speaking of the Southern Philippines as being the weak

link in regional security and began to call for trilateral maritime

policing in waters to the north and northeast of Sabah .

There was a most un-ASEAN drumbeat of threats by Indonesian civilian and

military leaders to engage in unilateral

military operations to rescue their sailors. On 27 April, Philippine

President Aquino acquiesced

to Indonesian and Malaysian calls for joint maritime patrols based on the joint

operations in the Strait of Malacca .

On 5 May, the three foreign ministers met and issued a communique “recognized

the growing security challenges, such as those arising from armed robbery

against ships, kidnapping, transnational crimes and terrorism in the region,

particularly in reference to the maritime areas of common concern.”

To conduct patrol among the three countries using existing

mechanisms as a modality;

To render immediate assistance for the safety of people and

ships in distress within the maritime areas of common concern;

To establish a national focal point among the three

countries to facilitate timely sharing of information and intelligence as well

as coordination in the event of emergency and security threats; and,

To establish a hotline of communication among the three

countries to better facilitate coordination during emergency situations and

security threats.

They instruct the relevant agencies of the three countries

to meet as soon as possible and subsequently convene on a regular basis to

implement and periodically review the above-mentioned measures and also to

formulate the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP).

With the agreement in principle, the sides had to negotiate

a standard operating procedure, which had to have more teeth than a

poorly implemented 2002 trilateral agreement to respond to Abu

Sayyaf attacks.

On 20 June, the Malaysian, Indonesian, and Philippine

Defense Ministers agreed to establish transit

corridors. “The ministers have agreed in principle to explore the

following measures, including a transit corridor within the maritime areas of

common concern, which will serve as designated sea lanes for mariners,” they

said in a joint statement. In addition, they pledged to increase the number of

air and sea patrols as well as maritime escorts.

Most controversially, the draft SOP will allow for the right

of hot pursuit, something that the Indonesians insisted on. The Indonesian

Minister of Defense, Ryamizard Ryacudu told the media

“We’ve agreed that if another hostage situation occurs, we will be allowed to

enter [Philippine territory].” His Philippine counterpart, Voltaire Gazmin, who

was in the last week of his job, qualified

the agreement: the hijacking/kidnapping must have taken place in

Indonesian waters, before Indonesian vessels could enter Philippine territory,

and Philippine security forces would have to be immediately informed so that a

“coordinated

and joint operation could immediately be undertaken.”

Limitations

Even if the three countries implement the SOP and begin

implementing trilateral policing, there would be serious limits for seven key

reasons.

First, this is not the Strait of

Malacca , one of the most critical maritime straits in the world.

Those patrols, now in their 11th year, have been successful and resulted in a

dramatic drop in piracy and shipjackings. But they have benefited from members

with very robust capabilities, such as Singapore

and Malaysia , a critical

international chokepoint, and with technical support from the United States Strait of Malacca has the most

sophisticated network of radars and maritime domain awareness capabilities in

the region.

Second, sovereignty remains the paramount concern. No

country will allow “joint” patrols in their territorial waters. They might do

“coordinated patrols” in their respective national waters, but there will be no

joint patrols. Each country has been adamant on this point. As the Philippines

said, “’joint exercises” can only take place “in the high seas and not within

[Philippine] territorial waters.” As Indonesian Foreign Minister

Retno Marsudi put it, any joint actions “must be agreed on without

any of them sacrificing their sovereignty.”

Even the agreement on hot pursuit seems problematic. While Malaysia

Third, and more to the point, this really requires

Indonesian leadership. As we have seen, President Widodo’s Maritime Fulcrum

Strategy has been terribly

implemented, and he has shown little interest in compelling his

various services and ministries to come up with an integrated implementation

strategy, let alone serve as a regional leader of ASEAN. The Indonesian

military’s threat perception and budgetary allocation priorities have returned

to an inward

focus, after nearly a decade of maritime orientation.

Fourth, the capabilities of all three remain very limited.

There is an asymmetry between the threat and the capabilities deployed to

this region. Even though Malaysia

has beefed up maritime policing off of Sabah ,

especially following the incursion by Sultan

of Sulu-backed gunmen in 2013, it has not been enough to prevent the

ASG from still launching kidnappings. Malaysia

and Indonesia South China Sea have been

far greater priorities. But those limited capabilities are exactly why

cooperation is so necessary.

Fifth, there are still significant suspicions between the

countries and lingering border disputes. The Indonesians remain distrustful and

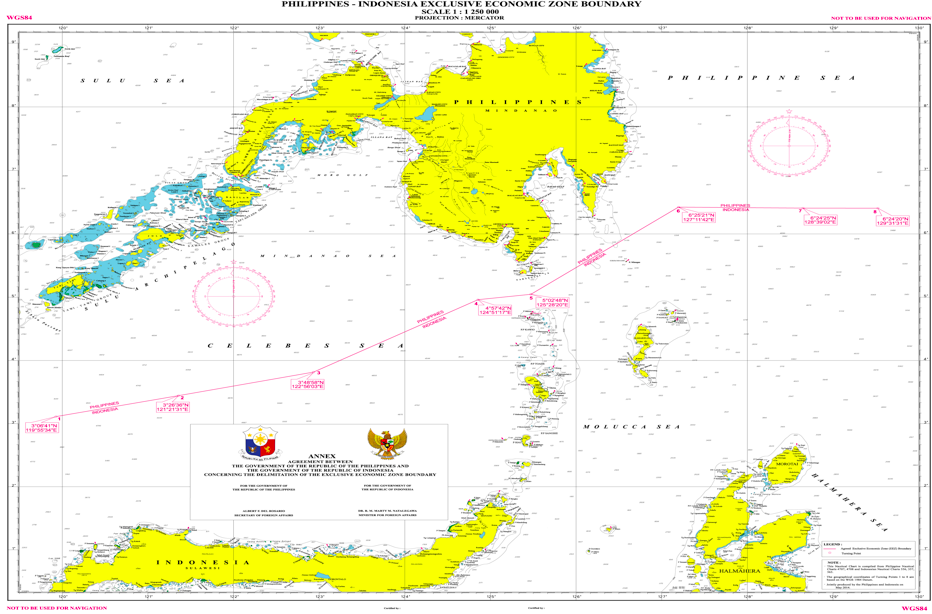

angry towards the Malaysians over the maritime demarcation between Sabah and East Kalimantan in the Ambalat

region. On 26 June, Indonesian jet fighters intercepted

a Malaysian military cargo plane flying too close to Natuna Island Indonesia and the Philippines successfully demarcated

their maritime boundary in 2014, Malaysia

and the Philippines do not

have a formally demarcated maritime border owing to the disputed claim over Sabah . That may possibly worsen as president elect

Duterte stated that he would revive the Philippine claim

to Sabah which had been dormant for number of years.

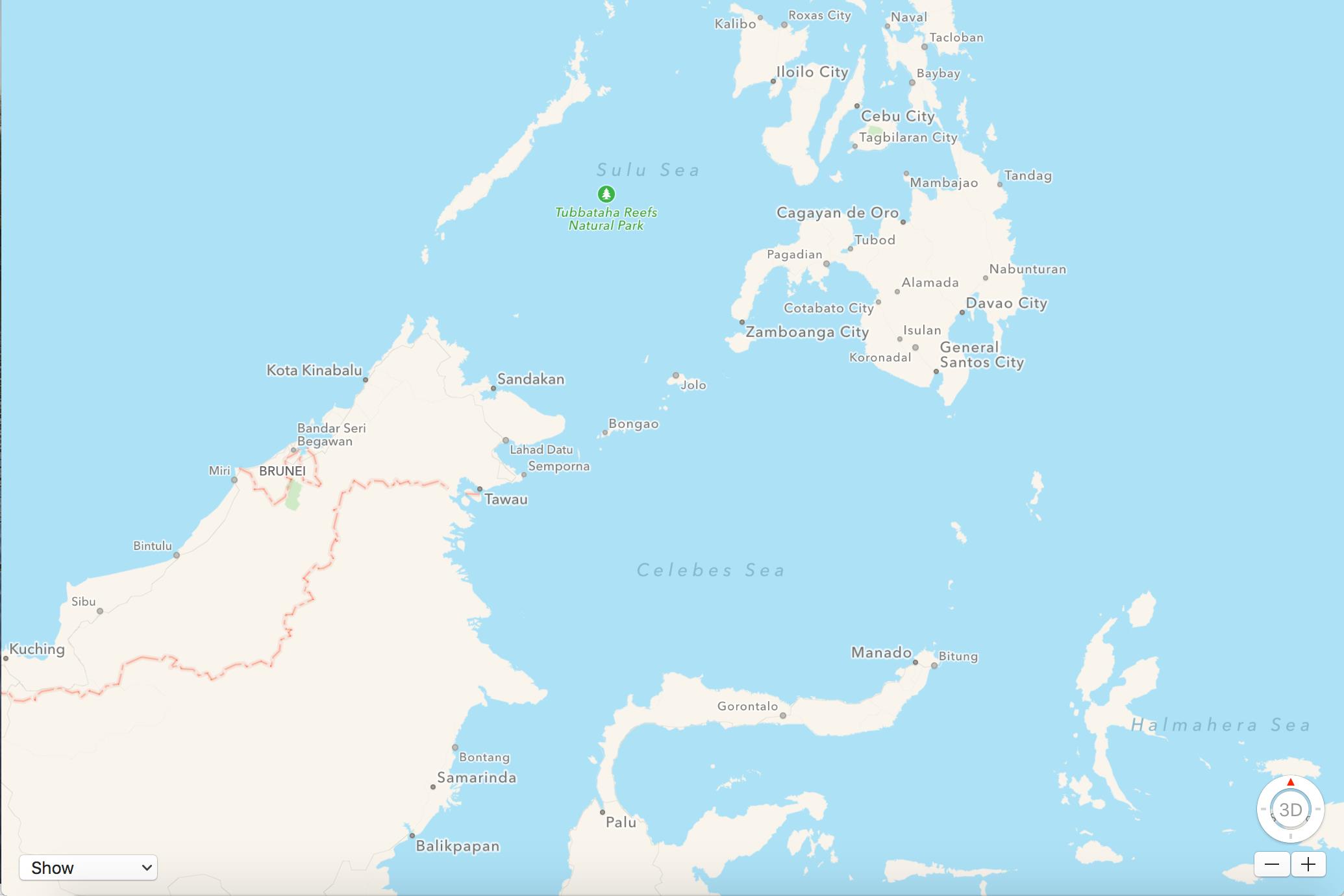

Sixth, one needs to study a map of the trade routes to understand that even if there is international cooperation as well as designated corridors, they will only have a limited impact.

A majority of Abu Sayyaf operations occur in Philippine

waters, and only a small portion occur in waters that may have joint patrols.

If militants want to avoid Indonesians exercising their right to hot pursuit,

they merely have to wait for targets to enter Philippine waters. Manila is unlikely to allow armed convoys from Malaysia or Indonesia Philippines

actually has is primarily focused on their maritime claims in the South China Sea .

The Sulu and Celebes

Seas

Even if we take away the large LNG tankers and large

container ships that come up through the Lombok and Makassar Straights, which

then either continue on to Northeast Asia to the east of the Philippines or cut

through the deep waters between the Malaysian state of Sabah and the Tawi Tawi

Islands of the Philippines, there are simply too many small tugboats, small

bulk cargo ships, and tramp steamers that ply those waters to protect.

Ships coming out of Balikpapan

and Samarinda in East Kalimantan or Makassar and Monado on Sulawesi traveling

across the Celebes Sea to General Santos or Davao

in the Philippines Manila Manila , Cebu, or ports in northern Mindanao can operate at the furthest edges of Abu Sayyaf

capabilities. But ships from there or from the port

of Sandakan going to Zamboanga or east

to General Santos or Davao

Again, the ASG can operate close to shore, in Philippine

waters, without triggering the right of hot pursuit. And even if Indonesian or

Malaysian forces were able to operate in hot pursuit, only on sea; they can do

nothing when the Abu Sayyaf reach shore.

Finally, the lesson of Somalia United States

since 2002, the Armed Forces of the Philippines

Indeed, there is growing evidence that new kidnap for ransom

gangs are carrying out operations, and then selling

their captives to ASG leaders such as Al Habsyi Misaya. The six

Indonesian sailors who were not taken hostage on 20 June recounted that their

seven colleagues were taken by two

separate groups with very different behavior and

professionalism.

It is yet to be seen what approach president-elect Duterte

will take. Like most issues, he has said one thing and immediately contradicted

himself. He has has prided himself on the use of extra-judicial killings to

eliminate Davao

Duterte recently warned that he would not continue the Armed

Forces of the Philippines

In short, trilateral policing can only deliver so much until

the capabilities of the Philippines China United States and other

partners such as Australia

and Japan

Tempered Expectations

The frustration on the part of the Indonesian and Malaysian

governments is palpable. In addition to hurting trade, a number of land-based

kidnappings in Sabah since 2013, have impacted

tourism. Malaysian Foreign Minister Datuk

Seri Anifah Aman was blunt in calling for a meeting with his new

Philippine counterpart following the 30 June inauguration of President Duterte:

“We need to have this urgent meeting. I would like to stress

upon the seriousness of this problem that involves Filipino nationals. We

accept that it is a complex issue. The Philippines military has been going

after these people with limited success. The question now is how can we work

together.”

So what can we expect? There may be some coordinated

patrols,but expectations about what these entail should be low. These navies

and maritime law enforcement organizations do not have a great track record of

working together in this area, which for all three countries has received a

disproportionately low share of their respective maritime security

budgets.

That they are even discussing them and trying to come up

with standard operating procedures is well and good. But this will need

to be routinized and taken to a higher level if it is to succeed. Perhaps

external actors, including the United States, Australia, Japan, and even

Singapore, can help bridge some of the gaps.

The three sides are discussing database and intelligence

sharing on local extremists and militants. There have been suggestions of

establishing joint

military command posts, yet undefined. But an actual fusion center

as what was established in Singapore seems a long way off, and the reality is

that none of the three has adequate maritime domain awareness capabilities.

With regional trade dominated by slow tugboats and tramp

steamers, even groups with limited capabilities such as Abu Sayyaf can wreak

havoc in the Sulu and Celebes Seas. With limited capabilities amongst the three

littoral states, there is an imperative to cooperation, especially considering

the importance of regional trade. Yet a history of mistrust, continued border

disputes, a fixation on sovereignty, and a lack of leadership is making the

necessary cooperation more difficult to achieve.

[Zachary Abuza, PhD, is a Professor at the National War

College where he specializes in Southeast Asian security issues. The views

expressed here are his own, and not the views of the Department of Defense or

National War College. Follow him on Twitter @ZachAbuza.]

[Featured Image: A navy cutter patrols the shores of a

fishing village near the capital town of Jolo in the southern Philippine

province of Sulu 30 June 2000 as an outrigger races across its path. (AFP PHOTO)]

http://cimsec.org/trilateral-maritime-patrols-sulu-sea-asymmetry-need-capability-political-will/26251

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.