Ten years ago, Ces Drilon, together with two ABS-CBN cameramen, were in Sulu to interview the controversial one-armed Abu Sayyaf leader Radulan Sahiron. But after many hours of walking to the Abu Sayyaf camp, they were told they have been kidnapped for ransom.

In this account the editor Carlo Tadiar asked her to write for the defunct publication Metro Him in 2008, the celebrated journalist recounts in great detail her 10 harrowing days in captivity, surviving the threat of being beheaded, and the arduous road to their release. But this piece is also about the two cameramen, Jimmy Encarnacion and Angel Valderama, who couldn't have been more dissimilar to the men who threatened their lives.

The mid-afternoon downpour had long stopped. But the man kept his camouflage raincoat on, with only the nose of his rifle jutting out. The rain did nothing to cool the air, so oppressive was the heat entrapped by the thick vegetation. I espied the man as he sat on the ground, the hood of the raincoat now hanging from his nape, his hair drenched with sweat. I wondered why he would not take his raincoat off. It was not until the following day that I got my answer. After I was told we were being held for ransom, I saw the man in the raincoat with only a T-shirt on and I realized he had only one arm.

He was Sulayman Patta. Commander Tek and Commander Harris were his aliases, I was to learn from the military, after our release. Among all our captors, he was the one I was to communicate with the most, having been assigned by the commander to relay his instructions to us. In the most frightening moment of our captivity, he looked at me with blazing eyes and told me that I and my team would die in the jungle.

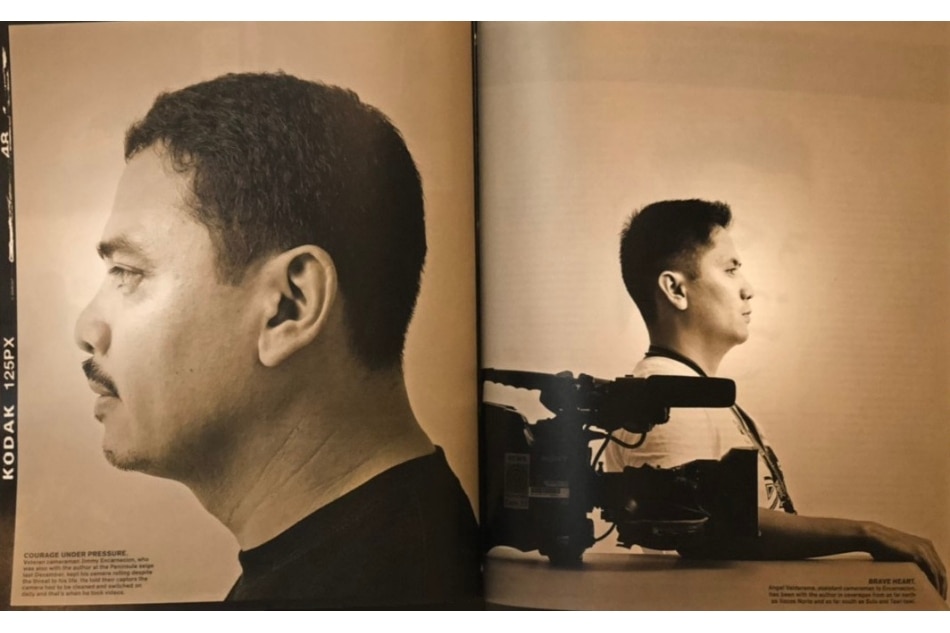

Jimmy Encarnacion and Angel Valderama were members of my team for the coverage in Sulu. In the last two and a half years, they were my regular companions in my out-of-town coverages, which brought us to as far north as Ilocos Norte and as far south as Sulu and Tawi-Tawi. But this time, I was not to rely on them for our story to get to air in time for the evening news. I was to lean on them for our very survival. Jimmy and Angel were my protectors during our captivity. The respect they showed me was picked up by our captors who addressed me as “ma’am” as Jimmy and Angel did. The two would look after my welfare, even washing my soiled clothes for me. They had no recrimination for me, even if I had repeatedly asked them for forgiveness for bringing them into danger. In our darkest moment, Jimmy reached out for my hand and we prayed. Our quiet prayer gave me the strength and calmness I so desperately needed when all seemed so hopeless.

The man leading us is Sulayman Patta, who wore a camouflage raincoat, followed by the man we nicknamed Babyface because he used the toner with the brand RDL Baby Face Kalamansi. Babyface was very fastidious about his looks. He brushed and combed his hair all the time and sprayed himself with baby cologne. He also shampooed his hair regularly compared to other men. When we were walking to our freedom, and I complained that i was getting so sweaty, he sprayed me with his cologne.

All throughout our captivity, I marveled at our surroundings and how it was a stark contrast to the brutality of the men who had control over us. On our second day, I began to write a journal. And in one of my first entries, I wrote:

“During the day, when you gaze at the deep blue sky or at night as you look up to the darkness dotted with stars and a crescent moon, you wonder how the Sulu sky can shelter such cruelty.”

When I watched the sunset during the days of our captivity, I had to hold back my tears. It was my favorite time of day. When I admired the scenery, the men would mock me. It was very odd that the men did not appreciate their surroundings, especially when they claim the land as rightfully theirs. The contrast could not have also been starker between the band of armed men who held me and my news team. I was witness to the display of perverted masculinity among our captors, and yet in moments of utter hopelessness was uplifted by the quiet bravery of Jimmy and Angel.

This is me sitting on a hammock beneath our plastic roof, writing in my journal.

All throughout our nine nights in Sulu, I was surrounded by men. My only encounter with women was on the second day when we walked through a small community atop a mountain. I would look into their eyes as if begging for help, our kidnappers forbidding us from uttering a word. The few houses we saw became sparser and sparser as we moved deeper into the jungle. I always made sure I was never too far from Jimmy, Angel and Professor Octavio Dinampo, who arranged the interview with Radulan Sahiron, the reported new amir of the Abu Sayyaf Group. I had also learned through a source in the legislature, Sahiron, a former warrior of the MNLF who had joined the Abu Sayyaf, was sending surrender feelers to the Arroyo administration. The source had informed me Sahiron had written a letter to a top security official, exploring the possibility of laying down their arms. President Arroyo, in a meeting with several legislators from the south had reportedly given a Sulu congressman the go-ahead to initiate contact with Sahiron.

Throughout our ordeal, four to five armed men would be assigned to us as our closed-in guards, watching over us during the day. At night, one or two would always be on alert, taking turns to check on us. The group would make a list of assigned guards every hour as darkness enveloped our camp. In my journal, I wrote:

“I’ve always had a romanticized view of Sulu, that outlook was shattered today. What turned these young men into the monsters that they are? What went wrong? They laugh, chat and joke around like any other Pinoy male but they have a deep hatred and a warped sense of the Muslim struggle. My mistake was in being so naïve in hoping that the man I was to interview would present a different view of the Abu Sayyaf. I was wrong. Apparently the message never even got to him. Greed and hatred got in the way. If we are to believe the commander in charge, he just decided to form a team to kidnap us for ransom.”

This is our walk to freedom. We trekked for about six hours before we were released.

The Muslims’ quest for self-determination has been a running story I had been covering since I began my career as a journalist almost 25 years ago. I was present when the chief government negotiator under the newly installed Aquino government, Ambassador Emmanuel Pelaez, met with MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari for the first time in Sulu in 1987. In 2001, shortly after Gloria Arroyo assumed power, I had gone to Libya to cover the beginning of peace talks between the newly established Arroyo government and the MILF.

I had gone to the camps of the MNLF and the MILF and have seen their warriors brandishing their high powered firearms. But our captors whom I believed to be members of the Abu Sayyaf were of a different breed. Where I had been in search of an ideology, I had only found a lust for money.

A rendering of Abu Sayyaf's Sulayman Patta by CIDG.

It was not so much that they were men and I was the lone woman that kept me powerless and in fear. As a journalist who had dealt with men from various walks of life, gender was not a big issue for me. But these were men who used the barrel of the gun and their Islamic faith to get what they wanted: money. They did not perform any military drills during our time in the jungle but they were disciplined in practicing their faith. The men would lay down their arms to pray three times a day, spreading their plastic sacks on the muddy jungle floor. In the first days of our captivity, I had urged Professor Dinampo to join them in prayer, but he refused, saying he could not be with them who had a prostituted view of their faith. But as our stay in the mountains wore on, he had relented and the morning after Angel was released, he prayed with them at the crack of dawn.

The guns were not pointed at us all the time and in the end, not a single shot was fired, but we were always in fear, even when the men would crack jokes with Angel and Jimmy. On our third day, three young boys joined the group, one of whom told me he was 12. He bore an armalite while guarding me as I bathed in a spring. He said he never went to school, but he was old enough to carry a gun. I wondered as we returned to camp and as he sat in his hammock to watch over us if he really knew how to fire his weapon. Whenever the prospect of a lower ransom amount would be brought up as I spoke with my family, the men would regard us with contempt. They would pepper us with angry words, and the possibility that they would use their guns on us became very real. In one phone conversation I had with my sister Grech, she asked to speak to Commander Tek to tell him that our family could only afford P2M and to understand that ABS-CBN had a no ransom policy. One man remarked in the background, “Mag-umpisa na lang tayong magkuhay!” Alarmed, I had told my sister, “maybe we can borrow money from ABS-CBN.” The teenaged boys were particularly mean and would taunt and mock me. “Kawawa naman si ma’am, hindi nakikita ang mga anak niya." Kawawa naman si ma’am, they would recite in their high-pitched voices, over and over like a nursery rhyme. I was angered by them at first, and at one point, scolded one of them for their lack of respect; they were only as young as my sons. But then I realized, who could blame them with such men as their role models? As we walked to our freedom on our last day, I had urged a 17-year old boy, whom I had admired for his cooking skills, to go to school. His reply to me was, “No, I don’t want, I might even become an engineer.” These boys were convinced, bearing arms and fighting was the right path to take. His response broke my heart.

Our last camp prior to our being released. Leftmost is Prof. Dinampo, then Sulayman, then a man who introduced himself to Jimmy as "Brain Damage."

The fourth day

June 11 was our fourth day in captivity. It was my dad’s birthday. As a Lt. Colonel in the Philippine Army, it was he who had made places like Patikul, Maimbung and Jolo familiar to me. They were just postal addresses in his letters to me when I was in high school, when he served as a battalion commander in the south. But as a journalist and perhaps because of him, Sulu had a particular draw for me. My father had passed away in a helicopter crash fifteen years ago, but I could feel his presence in the depths of Sulu. I thought, this was a place where he had survived an ambush once, and in moments of despair I called on my father’s spirit for survival. Early in the day, as the Commander handed me my phone to call my family, I read a text my mother had sent, “Your release on your dad’s birthday will be his most beautiful gift to us.”

But it was not to be.

It was mid afternoon of that day when all the guns were pointed at us for the very first time. The men went berserk when I got off the phone with Vice Governor Lady Anne Sahidula. She had told me that all my family could afford to pay was P2M; the group was demanding P20M. Commander Tek, the one-armed man, was raving mad. When the phone was grabbed from me, he looked me in the eye and said we would die in the jungle. “Sanay naman kaming mabuhay sa gubat. Kaya naming mabuhay dito. Kayo mamamatay na lang kayo dito!” Jimmy's video camera was taken down from the camp. The men said they would just set fire to it. “Ang camera na ito ipapanggatong na lang namin!”

As I returned to my hammock, Jimmy said to me, “Ma’am ang mga baril nila nakatutuk lahat sa atin.” I was to afraid to look so I said to him, “Magdasal na lang tayo.” I began to pray the rosary, using my fingers to count my Hail Marys. Jimmy reached for my hand and we prayed quietly together. Before this, he whispered he had secretly taken footage of the camp we had just moved to. I realized that not only did we have to contend with the rage of the armed men over the ransom, we feared the footage may be discovered. Then my heart jumped when the men grabbed Jimmy and Angel, forcing them to kneel on the mud, tying their hands behind their back.

“Two million lang! Two million lang! Mababawasan pa yon!” one of our guards told Jimmy.

“Kailangan mag-ultimatum na tayo!” said Commander Tek.

If the full amount was not received by Indanan Mayor Alvarez Isnaji (the person they had chosen to receive the money for them) by 2 p.m. the following day, the men told us, Angel would be beheaded while Jimmy would film it with his video camera. “Ikaw Jimmy kukunan mo ang pagpugot ng ulo ni Angel, live!”

As for me, I was told to put makeup on. “Make-up ka nang make-up. Mag-make-up ka nang mabuti, para pag na-LBC ang ulo mo sa ABS-CBN, maganda ka!”

My line to my family was initially through my sister Grech, but later it was through my brother, Frank. His voice was always reassuring, calm and sober. I recall my voice breaking when he told me to be strong after I asked him to update all my insurance payments, “Remember, positive thinking,” he said. “Hang on, hang on. We’re doing everything we can.” I said sorry to him in another phone call and I was close to tears, “Don’t be sorry, don’t be. Everybody’s behind you here.”

But contact with my family was abruptly shut off when the crisis committee composed of ABS-CBN news executives, members of my family included, decided I should communicate solely with Vice Governor Sahidula. When I informed Frank about the ultimatum on Angel, it was to be our last conversation. The line was cut. It became the supreme test of faith for me. When I would try to call Charie Villa, my direct superior at the ABS-CBN newsroom, my call would be rejected. Grech’s phone was shut. There had to be a good reason, I explained to Jimmy and Angel. “May magandang dahilan kung bakit gano'n, hindi lang natin alam," I told them, "Huwag na tayong maghaka-haka pa, baka ma-depress lang tayo.” I discouraged any speculation. I told them we should not lose faith. We resolved to boost each other’s spirits. We agreed that if one is down, the others should cheer that person up. They were more than up to the challenge. I can only imagine the fear and the doubts running in their heads.

The possibility of rape

Our captors never laid a hand on me, until the eighth night of our captivity when I was roused from sleep in my hammock and my hands were bound in rope that they used to tie our plastic tents. And on our last day, I was slapped twice while talking on the phone to Senator Loren Legarda. The sound of the slap stunned me, but when the shock ebbed, I wondered why I didn’t feel any pain. Still, their brute force was palpable, even when they would lovingly clean their weapons in the morning before they would even have breakfast.

Jimmy Encarnacion and Angel Valderama as they appeared in the Metro Him feature. They were photographed by Milo Sogueco.

A number of the men wore their hair long. They had sachets of shampoo and hair conditioner with them. One proudly proclaimed he had a popular brand and gave me a sachet, the first time I bathed. The younger ones had toners and cotton to clean their face and keep acne away. We nicknamed one of the men “Babyface” because of his use of a particular brand called RDL Babyface toner. On the first day of our captivity, someone had taken the bronzer from my bag. On our last day, before we began our long walk to our freedom, the men had taken my cologne, pressed powder and make-up pouch. I was amazed that even in the depths of the jungle, the men would gaze at themselves in the mirror, cleaning their acne with toner and brushing their hair to a sheen.

The possibility of rape was a fear that hung heavy in the air for me. I never betrayed my anxiety to Jimmy and Angel. But the night Angel was freed, Commander Tek had hung his hammock so close to mine.

I had asked Professor Dinampo to speak to him as a fellow Tausug to keep a distance from me but he didn’t. In his testimony before the preliminary investigation on the case against the Isnajis, Professor Dinampo said that aside from the ultimatum on Angel, he overheard the men say they would rape me. It was the first time I had heard this from the Professor and my heart sank to the pit of my stomach. The Professor told the prosecution panel he kept it from me for fear I would become hysterical. That night in the jungle, when I heard the commander’s soft breathing as he fell asleep, I thought of reaching out for a bolo to slit his throat.

But survival was still primordial and I let the thought pass. It was not until the men who escorted Angel came back in a jubilant mood past midnight that they called the attention of Commander Tek, noting the closeness of our hammocks. They spoke in Tausug. After the exchange, the one-armed commander moved his hammock some distance from mine. The men had received part of the ransom then and were perhaps in a celebratory mood. Thoughts of rape were set aside.

The following day, Commander Tek teased me saying the men were jealous of him. “Nagseselos si Commander sa akin, ma’am,” referring to one man who always held my cellphone and the leader of the group that escorted Angel out of the camp. I ignored his comments. One time, one of the guards called my attention. I had folded my jeans below my knees to keep it from getting muddied up. The guard said such display was not allowed by the Muslim faith. “Ibaba mo ang pantalon mo, bawal yan sa aming mga Muslim.”

“Ayaw ko ding ipakita ang legs ko,” I told him as I rolled down my pants. I had to struggle to hide my revulsion.

With Prof. Dinampo

On the side of the authorities, there was Police Superintendent Winnie Quidato, the acting Chief of the Intelligence Division of the PNP-Intelligence Group and Marine General Juancho Sabban, head of Task Force Comet in Sulu. PSupt Quidato was just a voice on the phone for me at first. He introduced himself to me as an official of the DILG helping to secure our release. He had posed as a DILG official to monitor the movements of Mayor Isnaji and his son Jun, who was the initial contact of our kidnappers. It was his revelations after our release that convinced me that the father and son were not mere negotiators but were most likely co-conspirators of the group that held us.

On the morning we were released, the Isnajis were announcing the ultimatum had been lifted, as if they had complete control of the kidnappers. And yet up to the two o’clock deadline, Jimmy was threatened with being beheaded and I was being slapped. The revelation came as a shock to me.

General Sabban was a frequent contact in my various coverages in the south. He was beside me on our flight to freedom in the wee hours of the morning of June 18. He had picked us up from Mayor Isnaji’s residence shortly after our release. Upon seeing him, I apologized for not telling him I was in Sulu. Prior to my coverage, I had mulled telling him in confidence about my possible interview with Sahiron, but I had ditched the idea, planning to call him only after. I had thought confidentiality was of utmost importance for our safety. As a journalist, protecting one’s sources was primordial. But there was no need to say sorry; I believed he understood. I told him in the end, as I resigned my fate to God, I was hoping for his rescue mission. A text I had sent out to my family and ABS-CBN had apparently reached him, when about ten men left camp after Angel’s release, “Ten men left, and only about twelve men here. Now is the time to go delta.” Delta was my code for a rescue mission. He laughingly told me even President Arroyo had been informed about the message. Sabban’s men have since caught three suspected members of the Abu Sayyaf, one of whom had been caught on the video taken surreptitiously by Jimmy.

Jimmy’s video camera was kept in a plastic sack bag, but he had outwitted our captors. He told them he had to keep one side open so as not to trap the moisture inside. Jimmy had also told them the camera had to be cleaned and switched on daily and this was when he took video of them. In one moment of desperation, he confessed to me of being tempted to grab a gun from one of our young guards who kept watch while he bathed. But he said while he could have escaped, it would have put Angel and me in jeopardy. We were a team and we looked out for each other. No one’s interest was put above the others. It was vital for our survival. To be a real man does not mean having a gun and exercising dominance over the weak and defenseless; to be a real man is to show courage in the most trying and desperate of times.

During our ordeal, when death seemed imminent, my thoughts had turned to my sons, and I had scribbled a poem for them in my journal. They had endured my long hours in the field, when I would cancel family outings to hop on a plane at a moment’s notice to cover a breaking news story. I had just returned from a vacation in Los Angeles where one of my sons was taking college. We had just visited Disneyland, where they teased me no end for being too scared to enter one of its most popular attractions, the haunted house, when I would cover the most dangerous spots in the country for my news reports.

“It was a haunted house of make believe

And yet I was afraid to enter

And here I am deep in the lair of the Abu Sayyaf

That I so heedlessly sought admission

I open my eyes in the darkness

And in between the trees

Imagine figures floating, fleeting, watching

But all I make out in the darkness

Are the heavy steps that break the silence

And the guard opens his light on me and says

“ma’am, tulog ka ba?”

And for a second my hair rises on end

And I shiver in fear

How I wish

I had stepped in the haunted house of make believe my sons

Screaming in fright to your delight

My sons, I can’t wait

We will still do it someday"

.

This story first appeared in Metro Him Magazine September - October 2008.

https://news.abs-cbn.com/ancx/culture/spotlight/10/18/18/my-captors-my-men

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.