Trump’s second act in the South China Sea will have to be stronger than his first.

Lord Palmerston, the 19th century British leader and empire builder, famously noted that countries do not have eternal allies or perpetual enemies, only indefinite national interests. The tangled triangle of U.S.-Philippines-China relations is testing Palmerston’s maxim.

For more than a century, the Philippines has served a critical role in America’s rise as a world power. In turn, Manila has been one of the region’s largest recipients of U.S. foreign aid and military assistance. The people-to-people bond between the Philippines and United States is unique.

According to a 2015 poll by the Pew Research Center, 92 percent of Philippine residents held a favorable view of the United States (the highest in Asia). However, traditional U.S.-Philippine ties may be fraying under the new leadership of President Rodrigo Duterte, the former mayor of Davao City on the southern island of Mindanao.

The mercurial leader in Manila has verbally lambasted Washington while extending a hand to Beijing. Chinese President Xi Jinping has reciprocated through inducements such as infrastructure mega-projects and the relaxing of tensions in the South China Sea. Perhaps the Philippine legal triumph at The Hague has provided an opportunity for both parties to reassess their positions?

Regardless, the Trump administration is facing unchartered waters in its dealings with the Philippines and China. Already, the new White House has made a splash: issuing – and then retracting – specific threats of action in the South China Sea. The theatre of international affairs continues in the Asia-Pacific.

A Complex Relationship

The Philippines and the United States have a long and complex security relationship dating back to U.S. intervention during the Spanish-American War (1898-1902) – Washington’s introduction onto the world stage. The foundation of the bilateral relationship is the Mutual Defense Treaty of 1951. Under Articles IV and V, the countries have committed to protect the other against an “armed attack” in the “Pacific Area” of either party, including “on the island territories under its jurisdiction” or “on its armed forces, public vessels, or aircraft” in the Pacific. Washington has not formally extended the scope of its obligation to Philippines’ maritime claims in the South China Sea, such as over the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal. Nevertheless, President Barack Obama, when articulating his rebalance strategy, stated that “our commitment to defend the Philippines is ironclad.”

In the past, the Philippines-U.S. alliance has been subject to moments of revision and unease, owing in part to the trauma of U.S. colonial rule and dominant role in foreign affairs. For example, during the Cold War period, the U.S. maintained a large military presence at Subic Bay Naval Base and Clark Air Force Base. Following a close vote in the Philippine Senate (12 to 11) to revoke the Military Bases Agreement, these U.S. military bases closed in 1992. Subsequently, the countries entered into a Visiting Forces Agreement in 1998 that mandates that U.S. military forces assume a non-combat role and permits only a temporary (non-permanent) base of operations in the Philippines, reflecting Manila’s sovereignty concerns.

More recently, the 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) further deepened military ties. The EDCA is a 10-year, renewable arrangement, allowing for the rotation of U.S. military personnel and development of U.S.-built facilities and improvements, utilized rent-free by Americans, but owned by the Philippines. The EDCA allows for enhanced opportunities for joint-military exercises and modernization of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). For instance, the EDCA calls for increased Balikatan (“shoulder-to-shoulder”) exercises; 2016 witnessed the 32nd iteration of the joint U.S.-AFP war games.

The Philippines has also been a strong partner in U.S. counterterrorism efforts. The Philippines received designation as a Major Non-NATO Ally in 2003 following Manila’s support for the U.S. intervention in Iraq. The Joint Special Operations Task Force – Philippines (JSOTF-P) has targeted Abu Sayaf and Jemaah Islamiyah in Mindanao. U.S. special forces operate according to specifically crafted rules of engagement respectful of Manila’s sensitivities, acting in a supportive role and using force only to defend themselves or when fired upon.

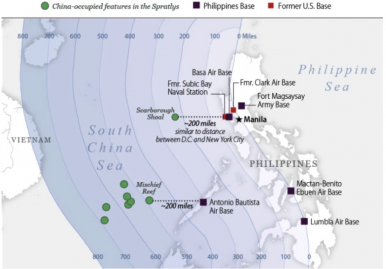

Increasingly, U.S. military support has been designed to increase the maritime capability of the AFP, considered one of the weaker militaries in the region. Last year, $42 million of more than $120 million in U.S. military aid to the Philippines fell under the U.S. Southeast Asia Maritime Initiative, which is designed to develop capacity of littoral states in the region. In March 2016, Washington and Manila identified five military bases for hosting rotating U.S. personnel, pursuant to the EDCA and consistent with Obama’s rebalancing strategy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Sites Selected for the Rotation of U.S. Forces

Source: U.S. Congressional Research Service

Of particular interests will be the stationing of U.S. forces at Philippines military bases near “hot spots” in the South China Sea such as Basa Air Base on Luzon Island, adjacent to Scarborough Shoal, and Antonio Bautista Air Base on Palawan Island, close to Mischief Reef and the Spratly Islands.

As a non-claimant, the United States has not taken a position on territorial disputes between the Philippines and China (or any other claimants) in the South China Sea. However, the Obama administration supported the Philippines’ efforts at The Hague and the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling, consistent with Washington’s desire for a peaceful resolution of disputes based on international law. Presumably the clear legal victory, a unanimous decision against China’s expansive claims in the South China Sea, would lead to even greater coordination between Manila and Washington. With the 2016 election of President Duterte, however, old assumptions in the U.S.-Philippines security alliance are being questioned.

The Space Between

Following Duterte’s inauguration last June, new space is developing between the Philippines and the United States. For instance, last September, Duterte made headlines with his colorful remarks directed at Obama following the latter’s critique of extra-judicial killings in Duterte’s “war on drugs.” Subsequently, Obama cancelled a scheduled meeting with the Philippines leader at the ASEAN Summit in Laos. This tit-for-tat has become representative of an acrimonious cycle – instigated by Duterte – that has left U.S. diplomats searching for answers.

Simultaneously, Duterte appears to have warmed to China. Among ASEAN members, the archipelago nation has traditionally been the least economically reliant on China, but this may be changing. During his trip to Beijing in October, Duterte received a pledge of $15 billion in investments. The parties have since exchanged high-level delegations and agreed to reconvene the Joint Commission on Economic and Trade Cooperation (JCETC) to institutionalize closer bilateral cooperation. Although the Philippines has enjoyed greater than 6 percent growth rates since 2010 and is projected to experience continued growth, the country’s economy requires infrastructure development if the Philippines is to become an upper-middle-income economy.

In contrast, on his first day in the Oval Office, President Donald J. Trump abruptly withdrew from the Transpacific Partnership (TPP) without offering any alternatives and casting doubt on longstanding U.S. commitments. For example, the Philippines is one of four countries that participates in the U.S. Partnership for Growth, a U.S. interagency effort that is aimed, in part, to help the Philippines prepare for joining the TPP. In turn, the Philippines and China are cooperating under the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a Chinese-led regional free trade agreement and alternative to the TPP. If Trump continues to make good on his campaign promises, then China may come to fill the void in world trade leadership.

Beyond the economic sphere, Duterte has signaled an intention to separate the Philippines from the long-standing U.S. security umbrella. Following his verbal skirmish with Obama, Duterte called for withdraw of U.S. special forces from Mindanao, part of the aforementioned JSOTF-P program, and directed his secretary of defense to buy weapons from Russia and China, as opposed to the United States. More recently, he has threatened to stop implementation of the EDCA, the agreement allowing the regular presence of rotating U.S. military personnel, claiming that the United States was creating a “permanent” weapons depot on Philippine soil, despite opposing restrictions under the VFA.

Even if the new Trump administration were to take a different or more aggressive interpretation of its treaty-relationship with Manila, it is an open question whether a Duterte-led Philippines would seek the additional protective cover. In comparison, newly-confirmed Secretary of Defense James Mattis recently reaffirmed U.S. policy that Japanese territorial claims in the East China Sea – the Senkaku Islands – are under the “administration” of Japan and, therefore, are included in the territories covered under Article V of the 1960 Japan-U.S. Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security.

By itself, Trump’s surprise U.S. election win has added a new element of ambiguity in international affairs. Nowhere is this new dynamic more clear than in the murky waters of the South China Sea.

Threats, Bluffs, and Inducements

Chekhov, the Russian playwright, once noted that if you introduce a gun in the first act, then surely the gun will be used in the third act. Otherwise, if the gun is not to be fired, it should not be placed on stage. The Trump administration has wasted no time in producing a new gun in the South China Sea dispute – the threat of specific military action.

In his prepared remarks during his Senate confirmation hearing, General Mattis observed that China’s behavior has led countries in the region to look for stronger U.S. leadership. The new Secretary of Defense promised “to defend our interests there—interests that include upholding international legal rights to freedom of navigation and overflight.” He also committed to uphold the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, as a reflection of customary international law, and “support policy measures designed to preserve and protect the continued global mobility of U.S. forces,” a reference to freedom of navigation operations in the East and South China Seas.

While those remarks reflected a continuation of the Obama administration’s policies, the newly confirmed Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, threatened new and precise actions.

During his Senate confirmation hearing, Tillerson vowed to send China a “clear signal” that “first, the island-building stops, and second, your access to those islands also not going to be allowed.” In support of this two-part threat, the former oilman described China’s ability to “dictate” the terms of passage through the South China Sea – where nearly half of the world’s trade traverses – as a “threat to the entire global economy.” Provocatively, Tillerson then compared China’s militarization and artificial island-building as “akin to Russia’s taking of Crimea.” The explicit link between Chinese and Russian territorial aggrandizement, beyond recognized international boundaries, may be the first for a senior Trump administration official. More importantly for the Asia-Pacific, the Trump administration announced its initial position in the South China Sea.

Already, this threat appears to be more bluff than buff – Mattis recently walked back any suggestion of a military enforcement action at this time. This waffling posture must be extremely awkward for the Trump administration, which has attacked its predecessor, often in personal terms, for its perceived weakness and lack of resolve. At least Beijing was pleased by this “clarification.” In an editorial, the Global Times, controlled by the ruling Chinese Communist Party, called Mattis’ statement a “mind-soothing pill.”

On the other hand, the White House surely vetted the confirmation testimony of Trump’s top diplomat with care and attention. Candidate Trump was not one to mince words. Now that specific military action has been promised as part of President Trump’s first act in the South China Sea, what can we expect in the third? The answer may lie somewhere buried in the hillsides of Luzon Island.

During his campaign, Duterte notably remarked that if China will “build me a train” then he “will shut up” about the South China Sea dispute. In January, Duterte secured Chinese funding for three large infrastructure projects on Luzon: a hydroelectric dam project costing $374 million, an irrigation project valued at $53 million, and a railway network appraised at $3.01 billion.

Duterte’s willingness to table enforcement of the PCA’s ruling has also led to informal cooperation in the Scarborough Shoal, where China has allowed the return of Filipino fisherman. He has even asked China for assistance with patrolling the high seas to combat maritime piracy and kidnapping, especially in the southern Philippines.

If Beijing can peel Manila away from Washington’s sphere of influence, then Trump may lose a key partner in his South China Sea strategy, to the extent he has formulated one. Superficially Presidents Trump and Duterte, both blunt-speaking leaders espousing a “law and order” philosophy, have much in common and, therefore, there may be an opportunity to reset the bilateral relationship. However, President Duterte’s apparent “pivot” towards China could evidence a deeper recalibration of the Philippines’ interests, instead of a quirk of personality, much like the United States is revisiting its posture on issues like free trade and globalization.

In the interim, China may take a “wait-and-see” approach with the new U.S. administration, as Beijing consolidates gains under warmer China-Philippines relations. I recently participated in a discussion on CGTN America’s current affairs show, The Heat, and one of my fellow panelists, Chen Xiaochen, a researcher at Renmin University in China, dismissed the recent bombast from senior Trump officials. He estimated that it may take a year before the relatively inexperienced U.S. administration adjusts to the “reality” of the new international environment.

But there is no intermission in the drama of the South China Sea. Trump’s second act will certainly have to be stronger than his first. It may arrive sooner than expected. And given his past rhetoric on tough leadership and enforcing threats, we cannot lose sight of Chekhov’s gun.

[Roncevert Ganan Almond is a partner at The Wicks Group, based in Washington, D.C. He has advised the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission on issues concerning international law and written extensively on maritime disputes in the Asia-Pacific. The views expressed here are strictly his own.]

http://thediplomat.com/2017/02/chekhovs-gun-and-the-tangled-us-philippines-china-triangle/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.