Reading the historic award in Philippines v. China raises several interesting questions.

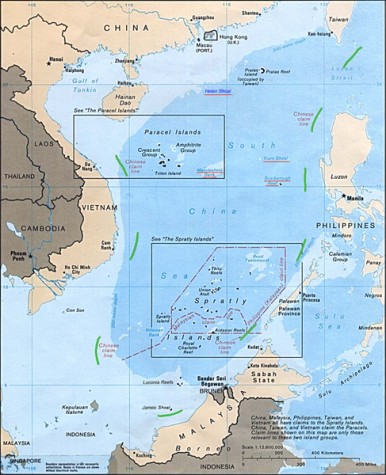

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/CIA

We’re hardly 12 hours out from the release of today’s historic award by a five-judge tribunal in The Hague on maritime entitlements in the South China Sea. The Tribunal, among other things, ruled China’s nine-dash line claim invalid and ruled in the Philippines’ favor on almost all counts. You can read my summary and early analysis of the award in a previous article here at The Diplomat. While I’m far from finished with the 500-page document, I do want to highlight some notable takeaways from my early reading of the award. (Readers may have caught some of these impressions on Twitter already, but it’s always good to avail of the longer form permitted here.)

Taiwan’s island isn’t an island. One of the big bang outcomes of the arbitration is the ruling on Itu Aba, the largest feature in the Spratlys occupied by Taiwan. Itu Aba had been a complicating factor in this whole dispute. While the case involved a filing by the Philippines against China, Taiwan possessed a feature at the center of the Spratly imbroglio that could have potentially been ruled an island under Article 121.3 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, generating a full 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ). This didn’t happen and Itu Aba is just a rock, like so many of the other features involved in the award.

My colleague Shannon has written about why the result is so deeply disappointing for the Taiwanese, but there’s a broader fallout that’s worth considering too. If Itu Aba isn’t an island on the account that it doesn’t support a “stable community of people,” it raises questions about other EEZ-generated possessions, like Wake and Midway Islands for the United States and Japan’s Okinotori claim (which I’ve discussed recently). The U.S. hasn’t ratified UNCLOS while Japan has. Meanwhile, the results of this award are binding on China and the Philippines, but will serve as a notable precedent in potential other cases of generously understood “islands.”

Let’s talk about Mischief Reef. In its ruling, the Tribunal decided that Mischief Reef, along with Second Thomas Shoal, is part of the Philippines’ continental shelf and falls within Manila’s EEZ. (Paragraph 647 outlines this in more detail.) As a low-tide elevation, it receives no special consideration for a territorial sea. As some readers may be aware, Mischief Reef also happens to be the site of one of China’s artificial islands. In paragraph 1177, the Tribunal remarkably notes that “China has effectively created a fait accompli” at Mischief Reef.

The Tribunal’s observation is correct. Mischief Reef now contains an illegally constructed Chinese dual-use facility on the Philippines continental shelf that a) cannot be reverted to its pre-artificial island state, and b) is highly unlikely to change hands. If Manila and Beijing do enter bilateral talks as per the Duterte government’s recent signals, this fact will loom as an awkward elephant in the room.

Finally, way back in October 2015, after the first U.S. freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) near Subi Reef, I made the incorrect prediction that Washington would opt to conduct a FONOP near Mischief Reef, which was enticing as it likely had far fewer constraints, permitting a high seas-assertion FONOP instead of an innocent passage operation like the first three we’ve seen. The ITLOS award effectively confirms what I’d suggested about the feature, but it also makes it an acute flash point given U.S. commitments to the Philippines under the Mutual Defense Treaty.

Slice it any way, it seems likely that Mischief Reef, through China’s island-building, has been sealed in as a long-term flash point in the South China Sea.

China’s island-building made the Tribunal’s job a lot harder than it needed to be. Remember, when the Aquino administration in the Philippines decided to file an Annex VII compulsory arbitration under UNCLOS back in 2013, after the 2012 stand-off over Scarborough Shoal, the present seven Chinese artificial islands didn’t exist (though the features were Chinese possessions). China began building them up shortly thereafter, but the arbitration was always a motivating factor.

In its award Tuesday, the Tribunal notes as much: “China has undermined the integrity of these proceedings and rendered the task before the Tribunal more difficult.” The Tribunal effectively alleges that Beijing obstructed the swift carriage of an investigation. Reading pages 131 to 260 of the decision, it’s apparent, for instance, how much work went into ascertaining the pre-reclamation status of some of the features that the Tribunal ended up ruling on. Given Chinese land reclamation and island-building activities, the Court resorted to pre-2013 hydrographic and navigational data from a variety of sources to make its decision easier (going back to early 20th century sources in some cases).

China’s non-participation in the case was always going to be an issue, but the award makes it clear just how deleterious Beijing’s activities in the Spratlys were to the Tribunal’s work.

China’s “own goals” in the South China Sea. Several paragraphs in the Tribunal’s award expose episodes of China shooting itself in the foot. For instance, there’s the Tribunal’s statement in paragraph 1164 that it would have found itself lacking jurisdiction over the seven artificial island-bearing features had China stated that they had military applications. Instead, the Tribunal “will not find activities to be military in nature when China itself has consistently resisted such classification and affirmed the opposite at the highest level.” Remember Xi Jinping’s pledge in the White House Rose Garden that the Nansha Islands (the Chinese name for the Spratlys) would not be militarized? Turns out that turned what could have been a less embarrassing verdict into a virtual calamity for China.

Other areas in the award–for instance, paragraph 209, on petroleum block assignment–highlight simple lapses in China’s conceptual framing of its position. In the aforementioned paragraph, the Tribunal points out that had China eschewed framing its entitlement to continental shelf rights in terms of the language of “historic rights” and used language consistent with UNCLOS, it may have had some luck with the Tribunal. Instead, the judges found that “the framing of China’s objections strongly indicates that China considers its rights with respect to petroleum resources to stem from historic rights,” which were declared invalid elsewhere.

One final example of the Tribunal underlining an “own goal” by China is in its reading of the nine-dash line itself. Paragraph 213 notes that China’s declaration of baselines in the Paracels and around Hainan contradicts its ambiguous claim to a territorial sea or internal waters within the area claimed by the nine-dash line. “China would presumably not have done so if the waters both within and beyond 12 nautical miles of those islands already formed part of China’s territorial sea (or internal waters) by virtue of a claim to historic rights through the ‘nine-dash line,’” it notes.

One wonders if China could have fared better on these counts if it had actively participated in the arbitration process, instead of refusing to participate and leaving its position up to the Tribunal’s interpretation based on a lone position paper, public statements, and past declarations.

Reduced bargaining space. One final takeaway from today’s award is somewhat counter-intuitive. The Philippines may have won a favorable award on nearly all 15 of its submissions, but that leaves the space for bilateral negotiation and “off ramping” with China limited. With Itu Aba a mere rock and the Spratlys reduced to a small collection of rocks with territorial seas and some LTEs, there’s little the Philippines can concede that would not involve the capitulation of something the ITLOS Tribunal has clarified is legitimately Manila’s under international law. For instance, concessions over Mischief Reef or Second Thomas Shoal (where the stranded BRP Sierra Madre sits) are out of the question unless Duterte wants to either face constitutional scrutiny under Article XII, Section 2 of the Philippines constitution or public outcry.

The one open door–somewhat poetically–is Scarborough Shoal, the disputed feature that led Manila to the court in the first place. (After the award, Scarborough is a disputed feature, albeit within the Philippines’ EEZ.) The Tribunal’s award leaves some space for the two sides to come to an agreement on joint resource exploitation. For this to work–in my personal read of the diplomatic situation–China would have to be both literally and figuratively the bigger country and make the first concession. (Chinese Coast Guard currently hold the chips for Scarborough Shoal, chasing away Chinese fishermen and sailors.) Manila isn’t in a position to make the first concession. Another option may be some form of energy exploitation bargain at Reed Bank, but that too has its complications, as Jeremy Maxie explores in The Diplomat.

Given China’s reaction to the award and the fact that, despite its legal propriety, the verdict will be read as another “national humiliation” in a long string of embarrassments, I don’t see Beijing taking the opening.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.