Posted to ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institue (Aug 2, 2022): 2022/76 “Piracy and the Pandemic: Maritime Crime in Southeast Asia, 2020-22” (By Ian Storey)

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 there were concerns that maritime crime in Southeast Asia would surge due to an expected global economic slump. In this picture, vessels are seen anchored along the southern straits of Singapore on 21 September 2021. Photo: ROSLAN RAHMAN/AFP.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 there were concerns that maritime crime in Southeast Asia would surge due to an expected global economic slump.Although incidents of piracy and sea robbery (PSR) in the region did increase in 2020 the numbers were much lower than during previous spikes. In 2021 the frequency of attacks declined to pre-pandemic levels.The worst PSR black spot in Southeast Asia was the Singapore Strait where the number of attacks has increased significantly since late 2019.The implementation of counter-PSR measures by regional states, both individually and collectively, ensured that the problem was largely contained during the pandemic.The 2021 trend lines have continued into 2022: the Singapore Strait continues to be a PSR black spot, while the number of attacks has declined in almost every other part of the region.In the second half of 2022, PSR incidents may experience a moderate increase due to economic problems caused by the Russia-Ukraine War.

[Ian Storey is Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute and co-editor of Contemporary Southeast Asia.]

ISEAS Perspective 2022/76, 2 August 2022

DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 there were concerns that maritime crime in Southeast Asia would surge due to an expected global economic slump.Although incidents of piracy and sea robbery (PSR) in the region did increase in 2020 the numbers were much lower than during previous spikes. In 2021 the frequency of attacks declined to pre-pandemic levels.The worst PSR black spot in Southeast Asia was the Singapore Strait where the number of attacks has increased significantly since late 2019.The implementation of counter-PSR measures by regional states, both individually and collectively, ensured that the problem was largely contained during the pandemic.The 2021 trend lines have continued into 2022: the Singapore Strait continues to be a PSR black spot, while the number of attacks has declined in almost every other part of the region.In the second half of 2022, PSR incidents may experience a moderate increase due to economic problems caused by the Russia-Ukraine War.

[Ian Storey is Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute and co-editor of Contemporary Southeast Asia.]

ISEAS Perspective 2022/76, 2 August 2022

DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION

INTRODUCTION

Piracy and sea robbery (PSR) is a perennial problem in Southeast Asia.[1] The geography of the region is characterised by large maritime spaces, sprawling archipelagos, and porous and contested sea boundaries. Regional navies, coast guards and other civilian maritime law enforcement agencies have limited resources to conduct patrols and monitor illegal activities in their countries’ territorial seas, large exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and expansive archipelagic waters. Inter-state cooperation to address the problem is sometimes constrained by sensitivities over sovereignty. Southeast Asia’s sea lanes, maritime choke points and harbours are among the busiest in the world, providing seaborne criminals with a target-rich environment. Corruption within the armed forces, civilian law enforcement agencies and port authorities exacerbates the problem. Poor socio-economic conditions in coastal communities often lead locals to turn to crime to make ends meet, especially during economic downturns.

Over the past two decades, however, Southeast Asian governments have enacted measures to improve security and crack down on crime in their ports, territorial waters and EEZs. And despite sensitivities over sovereignty and disputed maritime zones, regional states have established effective minilateral and multilateral initiatives to increase practical cooperation at sea and share information. As a result, PSR incidents in Southeast Asia have dropped dramatically, though the problem flares up periodically.

Historically, PSR incidents in Southeast Asia climbed during economic recessions, including during the 1997-1998 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis. Consequently, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, there were concerns that maritime crime in Southeast Asia would experience another surge. As countries closed their borders to contain the spread of the virus, ships were forced to ride at anchor outside ports and anchorages across the region, providing tempting targets for sea robbers. The contraction of commercial activities raised the prospect of economic hardship in coastal communities. And as governments were forced to divert financial resources to tackle the spread of the virus, the budgets for navies and coast guards were threatened with cuts.

Although PSR incidents experienced an uptick in 2020, they did not reach the same levels as previous spikes, and in 2021 fell to pre-pandemic levels. This article examines the PSR statistics over the past two years and attempts to explain why Southeast Asia did not see a tsunami of maritime crime during the pandemic. It concludes by offering an assessment of the situation in 2022.

Piracy and sea robbery (PSR) is a perennial problem in Southeast Asia.[1] The geography of the region is characterised by large maritime spaces, sprawling archipelagos, and porous and contested sea boundaries. Regional navies, coast guards and other civilian maritime law enforcement agencies have limited resources to conduct patrols and monitor illegal activities in their countries’ territorial seas, large exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and expansive archipelagic waters. Inter-state cooperation to address the problem is sometimes constrained by sensitivities over sovereignty. Southeast Asia’s sea lanes, maritime choke points and harbours are among the busiest in the world, providing seaborne criminals with a target-rich environment. Corruption within the armed forces, civilian law enforcement agencies and port authorities exacerbates the problem. Poor socio-economic conditions in coastal communities often lead locals to turn to crime to make ends meet, especially during economic downturns.

Over the past two decades, however, Southeast Asian governments have enacted measures to improve security and crack down on crime in their ports, territorial waters and EEZs. And despite sensitivities over sovereignty and disputed maritime zones, regional states have established effective minilateral and multilateral initiatives to increase practical cooperation at sea and share information. As a result, PSR incidents in Southeast Asia have dropped dramatically, though the problem flares up periodically.

Historically, PSR incidents in Southeast Asia climbed during economic recessions, including during the 1997-1998 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis. Consequently, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, there were concerns that maritime crime in Southeast Asia would experience another surge. As countries closed their borders to contain the spread of the virus, ships were forced to ride at anchor outside ports and anchorages across the region, providing tempting targets for sea robbers. The contraction of commercial activities raised the prospect of economic hardship in coastal communities. And as governments were forced to divert financial resources to tackle the spread of the virus, the budgets for navies and coast guards were threatened with cuts.

Although PSR incidents experienced an uptick in 2020, they did not reach the same levels as previous spikes, and in 2021 fell to pre-pandemic levels. This article examines the PSR statistics over the past two years and attempts to explain why Southeast Asia did not see a tsunami of maritime crime during the pandemic. It concludes by offering an assessment of the situation in 2022.

PIRACY AND SEA ROBBERY DURING THE PANDEMIC

Several organisations collect and publicly disseminate statistics on PSR incidents in Southeast Asia. The two most well-known are the International Maritime Bureau’s Piracy Reporting Centre (IMB-PRC) in Kuala Lumpur, and the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia’s Information Sharing Centre (ReCAAP-ISC) in Singapore. The IMB-PRC is a non-governmental organisation set up in 1992 and funded by private companies in the maritime sector.[2] ReCAAP is an intergovernmental agreement signed by 14 countries in 2004 but which now has 21 contracting parties, including the United States and several European countries.[3] ReCAAP established the ISC in 2006 to facilitate information exchange and operational cooperation among the contracting parties. A third source of PSR statistics is the Information Fusion Centre (IFC). The IFC was established in 2009 as a multinational maritime security information sharing centre and is hosted by the Republic of Singapore Navy at Changi Naval Base.[4] A fourth source of data is the Maritime Information Cooperation and Awareness Center (MICA) operated by the French Navy in Brest, France.[5]

The data provided by the four organisations do not, however, provide a complete picture of the PSR situation in the region. Ships masters are sometimes reluctant to report PSR incidents because it leads to journey delays and raises their company’s insurance rates. This results in the issue of under-reporting. Due to political sensitivities, the IMB-PRC and ReCAAP-ISC assign different geographical descriptors to the location of PSR incidents, i.e. the latter uses more neutral geographic descriptors such as “Straits of Malacca and Singapore” or “South China Sea” instead of pointing to specific countries, especially Indonesia which has always been sensitive about the problem. Geographic definitions of Southeast Asia vary. For example, the IMB-PRC places Vietnam in East Asia rather than Southeast Asia, while MICA includes Papua New Guinea as a regional state. Nevertheless, the data from all four organisations provide an invaluable source of information for maritime security analysts.

For the period 2019 to 2021, the statistics from the four centres differ -sometimes markedly-but demonstrate the same overall trends: that during 2020, the first year of the pandemic, PSR incidents rose by 15-20 per cent in Southeast Asia but in 2021 declined to approximately the same level as in 2019 (see Table 1).

Table 1

Reports of PSR Incidents in Southeast Asia, 2019-2021

Reporting Agency 2019 2020 2021

IMB-PRC 55 66 57

ReCAAP-ISC 74 83 77

IFC 92 108 92

MICA 85 96 86

Sources: Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships Annual Report (London: International Maritime Bureau, various issues 2019-2021); Annual Report (Singapore: ReCAAP-ISC, various issues 2019-2021); Annual Report (Singapore: Information Fusion Centre, 2021); Maritime Security Annual report 2021 (Brest: MICA Center, 2022).

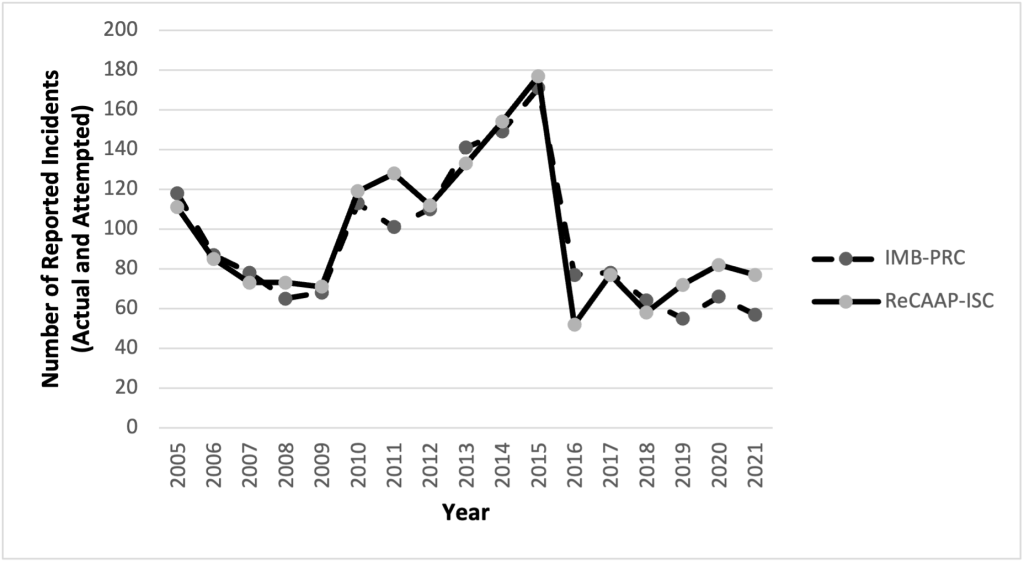

Although there was an uptick in incidents in 2020, the number of PSR incidents was lower than during previous spikes. As shown in Figure 1, maritime crime increased significantly between 2009 and 2011 due to the Global Financial Crisis, and from 2014 to 2015 when oil prices fell and criminal gangs hijacked small product tankers to siphon off fuel to sell on the black market. Moreover, the majority of attacks in Southeast Asia during the pandemic were opportunistic, involved low levels of violence, and largely petty theft from ships carried out during the hours of darkness.

Figure 1

PSR Incidents in Southeast Asia as Reported to the IMB-PRC and ReCAAP-ISC, 2005-2020

Several organisations collect and publicly disseminate statistics on PSR incidents in Southeast Asia. The two most well-known are the International Maritime Bureau’s Piracy Reporting Centre (IMB-PRC) in Kuala Lumpur, and the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia’s Information Sharing Centre (ReCAAP-ISC) in Singapore. The IMB-PRC is a non-governmental organisation set up in 1992 and funded by private companies in the maritime sector.[2] ReCAAP is an intergovernmental agreement signed by 14 countries in 2004 but which now has 21 contracting parties, including the United States and several European countries.[3] ReCAAP established the ISC in 2006 to facilitate information exchange and operational cooperation among the contracting parties. A third source of PSR statistics is the Information Fusion Centre (IFC). The IFC was established in 2009 as a multinational maritime security information sharing centre and is hosted by the Republic of Singapore Navy at Changi Naval Base.[4] A fourth source of data is the Maritime Information Cooperation and Awareness Center (MICA) operated by the French Navy in Brest, France.[5]

The data provided by the four organisations do not, however, provide a complete picture of the PSR situation in the region. Ships masters are sometimes reluctant to report PSR incidents because it leads to journey delays and raises their company’s insurance rates. This results in the issue of under-reporting. Due to political sensitivities, the IMB-PRC and ReCAAP-ISC assign different geographical descriptors to the location of PSR incidents, i.e. the latter uses more neutral geographic descriptors such as “Straits of Malacca and Singapore” or “South China Sea” instead of pointing to specific countries, especially Indonesia which has always been sensitive about the problem. Geographic definitions of Southeast Asia vary. For example, the IMB-PRC places Vietnam in East Asia rather than Southeast Asia, while MICA includes Papua New Guinea as a regional state. Nevertheless, the data from all four organisations provide an invaluable source of information for maritime security analysts.

For the period 2019 to 2021, the statistics from the four centres differ -sometimes markedly-but demonstrate the same overall trends: that during 2020, the first year of the pandemic, PSR incidents rose by 15-20 per cent in Southeast Asia but in 2021 declined to approximately the same level as in 2019 (see Table 1).

Table 1

Reports of PSR Incidents in Southeast Asia, 2019-2021

Reporting Agency 2019 2020 2021

IMB-PRC 55 66 57

ReCAAP-ISC 74 83 77

IFC 92 108 92

MICA 85 96 86

Sources: Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships Annual Report (London: International Maritime Bureau, various issues 2019-2021); Annual Report (Singapore: ReCAAP-ISC, various issues 2019-2021); Annual Report (Singapore: Information Fusion Centre, 2021); Maritime Security Annual report 2021 (Brest: MICA Center, 2022).

Although there was an uptick in incidents in 2020, the number of PSR incidents was lower than during previous spikes. As shown in Figure 1, maritime crime increased significantly between 2009 and 2011 due to the Global Financial Crisis, and from 2014 to 2015 when oil prices fell and criminal gangs hijacked small product tankers to siphon off fuel to sell on the black market. Moreover, the majority of attacks in Southeast Asia during the pandemic were opportunistic, involved low levels of violence, and largely petty theft from ships carried out during the hours of darkness.

Figure 1

PSR Incidents in Southeast Asia as Reported to the IMB-PRC and ReCAAP-ISC, 2005-2020

Source: Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships Annual Report (London: International Maritime Bureau, various issues 2005-2020); Annual Report (Singapore: ReCAAP-ISC, various issues 2007-2020).

Both globally and regionally, the number of PSR incidents dropped in the second year of the pandemic. The IMB-PRC recorded 132 global incidents in 2021, down from 194 in 2020 and the lowest recorded number since 1994.[6] ReCAAP-ISC reported 82 attacks across Asia in 2021, down from 97 in 2020, a drop of 15 per cent and the second lowest number of incidents since it started collecting data in 2007.[7]

The Singapore Strait as a PSR Black Spot

The most serious PSR black spot in Southeast Asia during the pandemic was the Singapore Strait. Approximately 100 km in length, over 100,000 vessels transit through the strait every year carrying billions of dollars in commodities and goods. The three littoral states, Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia, are responsible for security in their respective territorial waters which make up the strait. Even before the pandemic, the number of attacks in the Singapore Strait had been rising. The IMB-PRC received 12 reports in 2019 (up from three in 2018), rising to 23 in 2020 and 35 in 2021. In 2021, incidents in the Singapore Strait accounted for 61.4 per cent of all reports that year and the highest number since 1992.[8] The ReCAAP-ISC recorded 49 incidents in the Singapore Strait in 2021 (accounting for 60 per cent of all attacks in Asia) up from 34 in 2020. According to the ReCAAP-ISC, between 2019 and 2021, the majority of incidents occurred in the eastern sector of the Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS), in Indonesian waters in the Riau Islands, including Bintan and Batam. The attacks (most of which were non-violent low-level robberies) were conducted against larger ships – bulk carriers, oil tankers and general cargo ships – by gangs of between three to five men, mostly armed with knives.[9]

Several reasons may account for the surge in attacks in the Singapore Strait over the past several years. The economic problems caused by the pandemic are probably one reason, though not in 2019 of course. The IFC has suggested that the large number of incidents in the fourth quarter of 2021 (23 out of the 49 that year) may be attributable to unfavourable weather conditions (which prevented fishermen from going out to sea) and the approach of year-end festivities, causing locals to turn to petty crime to supplement their incomes.[10] Growing tensions between Indonesia and China in the South China Sea may provide another explanation. China’s expansive claims in the South China are represented by the so-called nine-dash line which overlaps with Indonesia’s EEZ around the Natuna Islands. In contravention of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), China claims “historic rights” in Indonesia’s EEZ, including fishing rights in the vicinity of the Natunas. In a push to enforce its claims, Beijing surged the number of China-flagged fishing boats into the area in late 2019 and early 2020.[11] The Indonesian government responded by rejecting China’s unlawful claims and increasing its military presence around the Natunas by redeploying warships from other parts of the archipelago including the Singapore Strait.[12] The IMB-PRC has noted that PSR incidents ceased off the Natunas in 2021.[13]

Why Wasn’t There an Upsurge in PSR Attacks During the Pandemic?

As the data from the four agencies indicate, PSR incidents in the region increased by 15-20 per cent in 2020, before falling back to pre-pandemic levels in 2021. Unlike during previous economic shocks, there was not a dramatic upsurge in attacks, except in the Singapore Strait. Why was that?

The IFC has put forward two theories to explain this: first, the imposition of movement restrictions by Southeast Asian governments and local authorities to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus; second, increased enforcement efforts by regional states.[14] The first reason probably did not have a major impact. The area which saw the biggest increase in incidents, Riau Province in Indonesia, was subject to movement restrictions that were both short-term (a few weeks at a time), not vigorously enforced and widely evaded.[15] They are unlikely to have affected the activities of sea robbers in the province.

The second reason is much more plausible: that the counter-PSR measures put in place by regional governments over the years effectively contained the problem. Three areas which were previously known as PSR black spots are worthy of examination: the Strait of Malacca; the Sulu-Celebes Seas; and regional ports and anchorages.

The Strait of Malacca is Southeast Asia’s busiest waterway and became the subject of international concern in the late 1990s and early 2000s due to the increasing number of PSR attacks.[16] In 2004, the three littoral states, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, established the Malacca Strait Patrols (MSP) to improve security in the strait (Thailand joined in 2008). The MSP consists of coordinated naval patrols, combined air patrols and information sharing networks. The MSP, together with a number of national initiatives launched at the same time, led to a sharp reduction in PSR incidents in the Malacca Strait. The IMB-PRC did not report a single attack in the busy waterway between 2016 and 2018. During the pandemic, both the IMB-PRC and ReCAAP-ISC reported only one minor incident in the strait, in 2021. The daily naval and air patrols by the MSP members appear to have exerted a strong deterrent effect on maritime criminals.

The Sulu and Celebes Seas – two large bodies of water connecting Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia – became an area of concern in the mid-2010s following a series of violent kidnapping-for-ransom incidents perpetrated by the criminal-terrorist organisation the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG).[17] In response to the attacks, in May 2016 the three governments agreed to establish coordinated naval and aerial patrols in the affected areas modelled on the MSP, though it was not until June 2017 that the Trilateral Maritime Patrols (TMP) were launched. However, more effective than the TMP were the counter-terrorism operations conducted by the Philippine security services against the ASG, beginning in July 2016, which significantly degraded the group’s ability to carry out attacks at sea. As a result, the number of incidents in the Sulu and Celebes Seas fell from 18 in 2016 to two in 2019. In 2020, one kidnapping-for-ransom occurred in the area but not a single incident was reported in 2021. Throughout the pandemic, the Philippine armed forces continued to conduct counter-terrorism operations against the ASG with a high degree of success.[18] Nevertheless, the ReCAAP-ISC continues to warn that the threat of abductions remains high and ships should exercise extreme vigilance.[19]

The vast majority of PSR incidents in Southeast Asia are acts of sea robbery, i.e. actual or attempted attacks that take place within the 12 nautical mile territorial sea limit of coastal states. To combat this problem, regional coast guards and other law enforcement agencies have strengthened security in their ports and anchorages. This has resulted in a significant decrease in acts of sea robbery in some of Southeast Asia’s major ports. Indonesia has been particularly successful. Under its 2014 Safe Anchorage programme, the Indonesian Marine Police increased patrols in 10 ports. The programme has contributed to a major decline in incidents in Indonesian waters (outside of the Singapore Strait): according to the IMB-PRC, from 43 attacks in 2017 to 25 in 2019, 26 in 2020 and nine in 2021. Data from the ReCAAP-ISC show a similar trend: from 33 incidents in 2017 to 22 in 2020 and 13 in 2021. The number of incidents in Malaysian and Vietnamese ports also fell between 2020 and 2021. In Manila there was an uptick in attacks during the pandemic due to the large number of ships anchored in the port awaiting crew changes. There were nine incidents of sea robbery in Manila in 2021. However, the Philippine Coast Guard has stepped up patrols in the harbour and arrested a number of the perpetrators.[20]

OUTLOOK FOR 2022

The 2021 trend lines continued into the first half of 2022. The Singapore Strait continues to be a PSR black spot. The IMB-PRC reported 16 incidents between January and June compared to 11 during the same period in 2020, and 16 in 2021 (62 per cent of attacks in Southeast Asia).[21] The number of incidents in Indonesia was up slightly from the same period last year –seven compared to five – but still far fewer than five years ago. The frequency of incidents in the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam continued to fall. Overall, the IMB-PRC recorded 26 attacks in Southeast Asia between January and June 2022, down from 35 and 28 during the first halves of 2020 and 2021 respectively.

The ReCAAP-ISC data track similar trends, recording 36 incidents in Southeast Asia in the first six months of 2022, compared to 35 attacks during the same period in 2021 and 47 in 2020.[22] ReCAAP-ISC received reports of 27 incidents in the Singapore Strait (all in Indonesian waters) compared to 20 in the first six months of last year. The number of incidents in Indonesia remained the same as January to June 2021 (six) while incidents continued to decrease in Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

Neither the IMB-PRC or ReCAAP-ISC received reports of actual or attempted attacks in the Strait of Malacca or Sulu-Celebes Seas between January and June 2022.

In the second half of 2022, PSR incidents in Southeast Asia could experience a moderate rise due to the economic impact of the Russia-Ukraine War which has led to rising food prices and increased economic hardship across the region. While national initiatives and inter-state cooperation have proved effective at managing the PSR problem, those measures need to be strengthened. In particular, Indonesia should allocate more resources for apprehending criminal gangs operating in its waters in the Singapore Strait. Enhanced cooperation among the littoral states, including enlarging the geographical scope of the MSP to include the Singapore Strait, may also help eradicate this PSR black spot.

The 2021 trend lines continued into the first half of 2022. The Singapore Strait continues to be a PSR black spot. The IMB-PRC reported 16 incidents between January and June compared to 11 during the same period in 2020, and 16 in 2021 (62 per cent of attacks in Southeast Asia).[21] The number of incidents in Indonesia was up slightly from the same period last year –seven compared to five – but still far fewer than five years ago. The frequency of incidents in the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam continued to fall. Overall, the IMB-PRC recorded 26 attacks in Southeast Asia between January and June 2022, down from 35 and 28 during the first halves of 2020 and 2021 respectively.

The ReCAAP-ISC data track similar trends, recording 36 incidents in Southeast Asia in the first six months of 2022, compared to 35 attacks during the same period in 2021 and 47 in 2020.[22] ReCAAP-ISC received reports of 27 incidents in the Singapore Strait (all in Indonesian waters) compared to 20 in the first six months of last year. The number of incidents in Indonesia remained the same as January to June 2021 (six) while incidents continued to decrease in Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

Neither the IMB-PRC or ReCAAP-ISC received reports of actual or attempted attacks in the Strait of Malacca or Sulu-Celebes Seas between January and June 2022.

In the second half of 2022, PSR incidents in Southeast Asia could experience a moderate rise due to the economic impact of the Russia-Ukraine War which has led to rising food prices and increased economic hardship across the region. While national initiatives and inter-state cooperation have proved effective at managing the PSR problem, those measures need to be strengthened. In particular, Indonesia should allocate more resources for apprehending criminal gangs operating in its waters in the Singapore Strait. Enhanced cooperation among the littoral states, including enlarging the geographical scope of the MSP to include the Singapore Strait, may also help eradicate this PSR black spot.

ENDNOTES

[1] Under international law, an act of piracy is defined as an illegal act of violence or detention involving two or more ships on the high seas i.e., outside a coastal state’s 12 nautical mile territorial sea. Acts of maritime depredation which occur within a state’s territorial or archipelagic waters are known as sea robbery or armed robbery against ships and are subject to the national jurisdiction of the state.

[2] See https://www.icc-ccs.org/piracy-reporting-centre

[3] See https://www.recaap.org/

[4] See https://www.ifc.org.sg/

[5] See https://www.mica-center.org/en/home/

[6] Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Annual Report 1 January 31 ̶ December 2021 (London: International Maritime Bureau, 2022).

[7] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to December 2021 (Singapore: ReCAAP-ISC, 2022), https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/reports/annual/ReCAAP%20ISC%20Annual%20Report%202021.pdf

[8] Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Annual Report 1 January 31 ̶ December 2021 (London: International Maritime Bureau, 2022).

[9] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to December 2021 (Singapore: ReCAAP-ISC, 2022), https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/reports/annual/ReCAAP%20ISC%20Annual%20Report%202021.pdf

[10] Annual Report 2021 (Singapore: Information Fusion Centre, 2022), https://www.ifc.org.sg/

[11] Hannah Beech and Muktita Suhartono, “China Chases Indonesia’s Fishing Fleets, Staking Claim to Sea’s Riches”, New York Times, 31 March 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/31/world/asia/Indonesia-south-china-sea-fishing.html

[12] “Jakarta: ‘No reason to negotiate’ with Beijing on South China Sea”, Benar News, 18 June 2020, https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/indonesian/response-letter-06182020173036.html; “Indonesian Navy Conducts Major Exercise amid South China Sea Tensions”, Benar News, 22 July 2020, https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/indonesian/naval-exercise07222020170545.html

[13] Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Annual Report 1 January 31 ̶ December 2021 (London: International Maritime Bureau, 2022).

[14] Annual Report 2021 (Singapore: Information Fusion Centre, 2022), https://www.ifc.org.sg/

[15] Francis E. Hutchinson and Siwage Dharma Negara,“The Riau Islands and its Battle with COVID: Down but not Out”, ISEAS Perspective, No. 25 (8 March 2021), /wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ISEAS_Perspective_2021_25.pdf

[16] See Sam Bateman, Catherine Zara Raymond and Joshua Ho, Safety and Security in the Malacca and Singapore Straits: An Agenda for Action (Singapore: Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies Policy Paper, May 2006); John Bradford, “The Growing Prospects for Maritime Cooperation in Southeast Asia”, Naval War College Review 58, no. 3 (Summer 2005); Ian Storey, “Securing Southeast Asia’s Sea Lanes: A Work in Progress”, Asia Policy, no. 6 (July 2008): 95-127.

[17] Ian Storey, “Trilateral Security Cooperation in the Sulu-Celebes Seas: A Work in Progress”, ISEAS Perspective, No. 48 (27 Aug 2018), /images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2018_48@50.pdf

[18] Michael Hart, “Abu Sayyaf Under Rising Pressure in Asia’s Backwater”, Asia Sentinel, 28 June 2022, https://www.asiasentinel.com/p/abu-sayyaf-rising-pressure-asia-backwater

[19] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to December 2021, pp. 35-36.

[20] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to December 2021, pp. 32-33.

[21] Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Report for the Period 1 January to 30 June 2022 (London: International Maritime Bureau, 2022).

[22] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to June 2022 (Singapore: ReCAAP-ISC, 2022), https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/reports/half-year/ReCAAP%20ISC%20Half%20Yearly%20Report%202022.pdf

[1] Under international law, an act of piracy is defined as an illegal act of violence or detention involving two or more ships on the high seas i.e., outside a coastal state’s 12 nautical mile territorial sea. Acts of maritime depredation which occur within a state’s territorial or archipelagic waters are known as sea robbery or armed robbery against ships and are subject to the national jurisdiction of the state.

[2] See https://www.icc-ccs.org/piracy-reporting-centre

[3] See https://www.recaap.org/

[4] See https://www.ifc.org.sg/

[5] See https://www.mica-center.org/en/home/

[6] Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Annual Report 1 January 31 ̶ December 2021 (London: International Maritime Bureau, 2022).

[7] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to December 2021 (Singapore: ReCAAP-ISC, 2022), https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/reports/annual/ReCAAP%20ISC%20Annual%20Report%202021.pdf

[8] Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Annual Report 1 January 31 ̶ December 2021 (London: International Maritime Bureau, 2022).

[9] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to December 2021 (Singapore: ReCAAP-ISC, 2022), https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/reports/annual/ReCAAP%20ISC%20Annual%20Report%202021.pdf

[10] Annual Report 2021 (Singapore: Information Fusion Centre, 2022), https://www.ifc.org.sg/

[11] Hannah Beech and Muktita Suhartono, “China Chases Indonesia’s Fishing Fleets, Staking Claim to Sea’s Riches”, New York Times, 31 March 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/31/world/asia/Indonesia-south-china-sea-fishing.html

[12] “Jakarta: ‘No reason to negotiate’ with Beijing on South China Sea”, Benar News, 18 June 2020, https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/indonesian/response-letter-06182020173036.html; “Indonesian Navy Conducts Major Exercise amid South China Sea Tensions”, Benar News, 22 July 2020, https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/indonesian/naval-exercise07222020170545.html

[13] Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Annual Report 1 January 31 ̶ December 2021 (London: International Maritime Bureau, 2022).

[14] Annual Report 2021 (Singapore: Information Fusion Centre, 2022), https://www.ifc.org.sg/

[15] Francis E. Hutchinson and Siwage Dharma Negara,“The Riau Islands and its Battle with COVID: Down but not Out”, ISEAS Perspective, No. 25 (8 March 2021), /wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ISEAS_Perspective_2021_25.pdf

[16] See Sam Bateman, Catherine Zara Raymond and Joshua Ho, Safety and Security in the Malacca and Singapore Straits: An Agenda for Action (Singapore: Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies Policy Paper, May 2006); John Bradford, “The Growing Prospects for Maritime Cooperation in Southeast Asia”, Naval War College Review 58, no. 3 (Summer 2005); Ian Storey, “Securing Southeast Asia’s Sea Lanes: A Work in Progress”, Asia Policy, no. 6 (July 2008): 95-127.

[17] Ian Storey, “Trilateral Security Cooperation in the Sulu-Celebes Seas: A Work in Progress”, ISEAS Perspective, No. 48 (27 Aug 2018), /images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2018_48@50.pdf

[18] Michael Hart, “Abu Sayyaf Under Rising Pressure in Asia’s Backwater”, Asia Sentinel, 28 June 2022, https://www.asiasentinel.com/p/abu-sayyaf-rising-pressure-asia-backwater

[19] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to December 2021, pp. 35-36.

[20] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to December 2021, pp. 32-33.

[21] Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Report for the Period 1 January to 30 June 2022 (London: International Maritime Bureau, 2022).

[22] Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia Annual Report January to June 2022 (Singapore: ReCAAP-ISC, 2022), https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/reports/half-year/ReCAAP%20ISC%20Half%20Yearly%20Report%202022.pdf

https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2022-76-piracy-and-the-pandemic-maritime-crime-in-southeast-asia-2020-22-by-ian-storey/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.