In May 2016, Rodrigo Duterte, the long-term mayor of Davao City, won a resounding victory in the Philippines national presidential election. He has since set in train a highly populist agenda that has seen internal security and stability as the main priority of his tenure.

My new report for ASPI—National security in the Philippines under Duterte: Shooting from the hip or pragmatic partnerships beyond the noise?—released today, looks at how Duterte has gone about securing his internal objectives and diversifying and rebalancing the country’s external alignments.

On assuming the presidency, Duterte ordered the army to prioritise the neutralisation of the Islamic State–affiliated Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) within a year, reiterating that mandate in the wake of the protracted 2017 Marawi crisis. He flooded the south with thousands of troops, requested the deployment of an additional 20,000 soldiers to safeguard areas where there were continuing threats, and declared an extended state of martial law across Mindanao.

These measures have been relatively successful. More than 350 militants were eliminated in 2017, and their ability to operate out of traditional strongholds in the south has been effectively degraded.

Duterte also sought to capitalise on ties he’d made with the left when he was mayor to bring an end to the protracted insurgency of the New People’s Army (NPA). His approach was conciliatory, and he quickly entered into four rounds of peace talks with the rebel movement.

Despite that promising start, little progress has been made in concluding a final deal. In November 2017, Duterte formally terminated all talks with the NPA. That was seen as an ominous development, possibly presaging the wholesale abandonment of the peace process. However, in April 2018, the president directed his cabinet to resume negotiations with the communist movement. How this will play out in terms of sealing a lasting settlement remains to be seen.

In March 2016, a surge of high-profile hijackings hit the tri-border area (TBA) between the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia in the Sulu and Celebes seas. Although no party has explicitly taken responsibility for the attacks, most commentators believe criminal elements within the ASG were the main culprits. Duterte mobilised specialist units from the army to destroy the group’s strongholds in Sulu and deployed the coast guard to intercept suspected pirate vessels. He also moved to collaborate with Indonesia and Malaysia in instituting a trilateral regime of maritime domain awareness in the TBA.

This combined unilateral and collective approach has resulted in a significant drop in attacks in the TBA. That said, there’s little room for complacency. The resilience of the ASG, combined with the size and archipelagic nature of the area to be monitored, means that the TBA will remain a potential maritime crime hotspot for the foreseeable future.

On the domestic front, one of Duterte’s main election pledges was to initiate an aggressive response to the Philippines’ growing drug problem. Not only did he promise that 100,000 dealers, addicts and traffickers would be eliminated, he also offered bonuses to the police for every criminal body they delivered. By the end of 2017, 4,000 had died at the hands of law enforcement and another 8,000 had been murdered by unknown assailants.

The global community has reacted with alarm at these figures and the apparent impunity with which the drug war is being conducted in the Philippines. In February 2018, the International Criminal Court opened a preliminary judicial inquiry into whether Manila’s policies warranted a full investigation of known human rights abuses.

Certainly, there are grounds to question the morality and utility of Duterte’s drug war. However, it’s important to note that his administration’s counter-narcotics strategy includes more nuanced strands of demand reduction and rehabilitation support. These underreported initiatives reflect a somewhat more coherent approach to dealing with the illicit drug trade and are more in line with the policies of governments in the West.

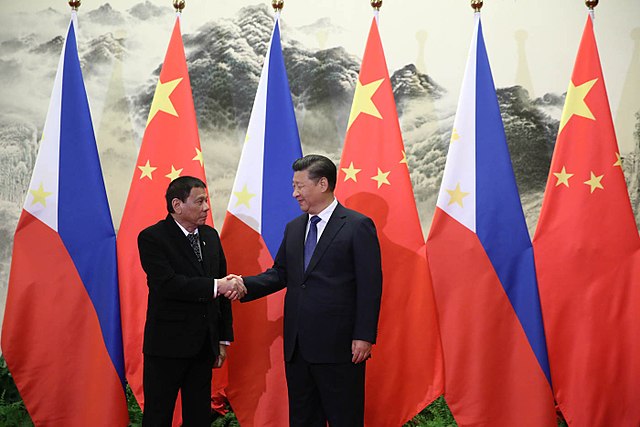

Duterte’s foreign policy has focused on configuring the Philippines’ external relations to maximise the time and space he has to pursue his domestic security priorities. To that end, he has embarked on two parallel courses of action. The first is resolving outstanding disputes with Beijing in the South China Sea in an effort to remove what was a key source of international distraction during the Aquino presidency. The second is adopting an ‘independent’ foreign policy that lessens the Philippines’ dependence on the United States while improving relations with China and other non-traditional partners such as Russia.

Despite this seemingly revolutionary stance on foreign affairs, it’s clear that his administration continues to view Washington—rather than Beijing or Moscow—as the ultimate security guarantor in Southeast Asia. Nearly two years into the Duterte presidency, there’s considerable continuity in American–Filipino relations. All the treaty foundations of the bilateral alliance remain intact. The two countries continue to conduct regular joint training exercises. And while some military engagements have been cancelled, new ones have been initiated in their place.

Rather than adopting an independent foreign policy, Manila appears to be moving more towards an ‘interdependent’ stance in its external relations, maintaining relationships with traditional partners (the US) while seeking to diversify ties with new powers (China and Russia). Although that may not have been Duterte’s original intent, it’s largely consistent with the postures of past presidents and is certainly the approach that would seem best for the Philippines’ national security today.

[Peter Chalk is an independent international security analyst based in Phoenix, Arizona. He acts as a subject matter expert on maritime security for the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. Image courtesy Philippine Government via Wikimedia Commons.]

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.