In a news clip coming out of the Marawi Siege, a group of people was able to touch base with the Maute group. In an ongoing siege, one way to end it is to establish communication between opposing groups to explore options for conclusion. What power or influence this does this group of people carry, inspite of an active war going on, the opposing sides talked? Why did the military allow them to proceed to the enemy side? Why did the Maute Group meet them?

As one working with this sector, one or two familiar faces were among this group referred as Ulama or religious leaders. In translation, they are also referred to as “religious scholars” or “religious professionals.”

Aleem Abdulmuhmin Mujahid, graduate of Islamic evangelism (Da’wah) from Islamic Call College in Libya is now Executive Director of the Regional Darul-Ifta’ (RDI) ARMM. In several fora, he outlined and explained why the need to mobilize the ulama.

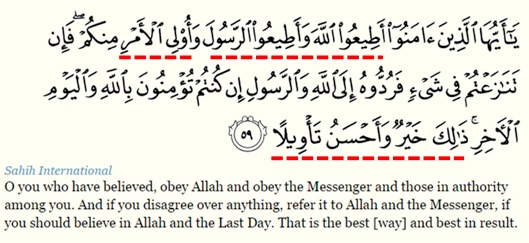

Point 1. “Ulil Amri” (those in authority) and obedience to them

The Arabic term “ulil amri” refers to those in authority. Who are these so-called people in authority from the Islamic perspective? In ayah (verse) 59, Surah (Chapter) 4: Al-Nisa’ of the Qur’an, spelling out three layers of obedience and putting obedience to those in authority after obedience to Allah and to the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). The same verse also puts forward a mechanism for resolution of conflict in obedience, i.e. referrence to the Qur’an and the Sunnah as a matter of belief.

In Islamic Jurisprudence, those in authority are the so-called ulama (religious leaders) and umara (politicial leaders). Together, they are composite of the collective leadership of the Muslim community. Thus their partnership is critical to Muslim development, as the Ulama take charge of moral and spiritual development, the umara take charge of the mundane development. In Tafsir ibn Kathir, certain ahadith (Prophetic sayings) were quoted to qualify obedience to these leaders and conditions for withdrawal of such.

The challenge here lies in the call for unity among religious and political leaders, vis-a-vis the current dissonance due to their differing political and developmental perspectives, to say the least. Imam Al-Ghazali once said, it is inappropriate and is not commendable for ulama to draw closer to the umara. Ulama who come into contact with the umara are categorized as bad. Then how should the ulama relate with the umara, and vice versa, to promote Islam and the welfare of Muslims?

Point 2. “Amaru bil ma’ruf wa nahaw anil munkar” (Enjoining right from wrong)

The Ulama carry the religious obligation to guide the spiritual development of the Muslims. In view of the contemporary challenge poised by violent extremism, there is a need for them to define, clarify and articulate the real teachings of Islam. Is it the hate and violence projected by the violent extremist groups?

In one of his lectures, Dr. Aboulkhair Tarason, the Grand Mufti of ARMM, reiterates the Islamic moderation (wasatiyyah) as the norm, and not extremism; humanity, not terrorism; therefore, another role of the Ulama is “amaru bil ma’ruf wa nahaw anil munkar” or enjoining right from wrong as stated in verse 41, chapter 22: Al-Hajj of the Qur’an.

The challenge of this role is this, how should we enjoin good and forbid bad in the 21st century environment where Muslims though indigenous as Moros are minority in a largely secular, Catholic-dominated environment?

Point 3. “Ummatan Wasatan” (Balanced, Just Nation)

In the first line of verse 143, chapter 2: Al Baqarah of the Qur’an, the Muslims collectively is viewed as “ummatan wasatan”; its meaning ranges from “just community” (Sahih International), to “balanced nation” (Al Muntakhab) and to “just and best nation” (Dr Al Hilali & Dr Muhsin Khan).

If Islam is about moderation and not extremism, then wasatiyyah is an antidote to ghuluww (excessiveness), tanattu’ (harshness), tashaddud (severity) and tatarruf (extremism)[1].

“The Wasatiyyah (Moderation) Concept in Islamic Epistemology: A Case Study of its Implementation in Malaysia”[2], enumerates a number of exegesis about this term.

For Al-Tabariy (1992:8-10), this means “the chosen, the best, the fair”. “Chosen” and “the best” because of the person’s characteristic of being fair. This differs from the extreme attitudes of the Jews and the Christians. The Christians said that Allah SWT has a son (who is Prophet Jesus a.s), while the Jews amended the holy scriptures destined from Allah SWT, killed the Prophets and lied to Allah SWT.

Ibn Kathir (1992:196-197) defines the term as the best, most humble and being fair.

For Al-Qurtubiy (1993:104-105), it means fair and the best. In this context, it does not mean taking a central or middle position in a matter, such as a position between good and bad.

Al-Raziy (1990:88-89) has four meanings: First, fair meaning not to take sides between two conflicting parties. In other words, fair here means to be far from both of the two extreme ends. When away from the extreme attitudes hence fairness would emerge. Second, something that is the best.

Third, the most humble and perfect. Fourth is not to be extreme in religious matters. For example, the extreme attitudes of the Christians and Jews. The Christian said that Allah SWT had children (Prophet Jesus a.s.), while the Jews tried to amend the holy scripture destined by Allah SWT to them and killed the prophets who received the divine deliverance.

For Al-Nasafiy (1996:132), this means the best and being fair. It is the best because of its central position. What is in the centre would be protected from anything that is dangerous compared to what is on the side and exposed to danger. It is said to be fair when it is not extreme or inclined towards some matter. For example, the Christians considered al-Masih (Prophet Jesus a.s) as God and the Jews had accused Maryam of adultery, who subsequently gave birth to Prophet Jesus a.s.

For Al-Zamakhsyariy (1995:1997) means the best and being most fair. Both these elements are characteristic of being central because whatever that is at the side is more likely to incline towards evil and destruction.

Al-Mahalliy & al-Suyutiy (t.t.:29) view the term as the chosen, the best and being fair

Qutb (1987:131) defines the term as good, humble, moderate, not being extreme at either end in relation to earthly and after-life matters.

For Hijazi (1992:81) means fair and the best. Fair here means not to be extreme in matters pertaining to religion or daily affairs. While “the best” is according to aspects of aqidah and human relations (between individuals or society) and not victimising or supressing other people.

Al-Zuhayliy (1991:8-9) opines that the term being fair, obedient to the teachings of Islam and not to be extreme to either end in religious and worldly affairs. In this matter, the Jews and Christians have to be discounted. The Jews are inclined to worldly matters and have neglected the after-life while the Christians lay too much importance on spiritual life that they neglect worldly matters.

When practiced in everyday life, people would not have an extremist attitude at either end of the spectrum when adhering to a belief, which is to accept the belief as it is (Abdullah Basmeih, 2001); not primarily pursuing earthly matters only and neglecting the after-life or vice versa (Ridhuan Tee Abdullah, 2010); and also not to pursue riches exclusively and in due process forgetting the unfortunate. (Mohd Shukri Hanapi, 2014).

Thus, wasatiyyah as social norms can be reflective of certains beliefs and attitudes consistent with Islamic prescrisptions – Life is sacred (5:32, 6:158, 17:33), overcome evil with good (13:22), neither be destructive nor malicious (4:29), no animosity to those who are not hostile to you (60:8), do not be aggressive ( 5:87, 2:190-193), pardoning is better than revenge (7:199), and no compulsion in religion (2:156).

The paper summarized the term wasata to mean the chosen, the best, being fair, humble, moderate, istiqamah, follow the teachings of Islam, not extreme to either end in matters pertaining worldly or the after-life, spiritual or corporeal but should be balanced between the two ends. (Mohd Shukri Hanapi, 2014).

The challenge for the ulama is how to move forward with wasatiyyah or moderation. Perhaps we should consider a number of consensus (ijma’) documents by eminent Islamic scholars and political leaders in the Muslim world. Within the Muslim community and in view of other religious minorities, the local ulama and umara need to consider the “Amman Message”. Across the larger Filipino community, they need to consider “A Common Word Between Us and You”. As we relate with non-Muslim minorities, we need to consider the “Marrakesh Declaration”.

Point 4. Understanding communal relations – Abodes of Peace, War, Covenant and beyond

Today, majority of Islamic scholars agree upon a classification into three. Shaikh Dr Yusuf Al-Qaradawi says, on Al-Shari’ah Wal-Hayah (Islamic Law and Life), Al-Jazeera Channel, dated Tuesday February 6th 2001, made clear these categories[3]:

Dar Al-Islam: The abode of Islam, the Muslim nations.

Dar Al-Harb: The abode of war, those that have declared war against Muslim nations.

Dar Al-‘Ahd: The abode of covenant, the countries that have diplomatic agreements and covenants with the Muslim nations.

Ulama associated with the the Moro liberation movement defined our state of affairs as one with the third category and point to the peace agreements that have been signed so far and and ongoing peace processes in trying to imagine and construct self-rule ourselves. The importance of honoring agreements is aticulated in the Qur’an, examples would be verses 4 and 7 of chapter 9: Al Tawbah.

Another point ulama need to consider is the New Mardin Declaration that revisited the fatwa of Ibn Taymiyyah and whose views on this division goes beyond the traditional three abodes.

Our Ulama therefore need to help the Moros journey through this legal nuance. Who has the authority to say we are in a particular category? How should Muslims, individually and collectively, behave under this category? What are our rights and responsibilities?

Point 5. Addressing ‘Amni” (peace, security) and “Khawf” (fear)

The verse 83, chapter 4: Al Nisa’ of the Qur’an, reminds us about how to treat information about security or fear and to whom these information should be referred to. This is the great burden of those in authority.

Thus, the Ulama need to go beyond and outside their comfortable zones of ‘madrasah’ and ‘masjid’. There is a growing number of extremist and terrorist groups misusing Islam by preaching hate, division and killing. The world is judging Islam by their action, not by the teachings of Islam.

In addressing peace and security, and eliminating fear, for the best interest of Islam and Muslim, how can the Ulama approach this security problem? Is it wrong to work with government to promote peace and security in Muslim community? How they lead in addressing the divide, i.e. skepticism, stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination?

In building “Aman” (peace, order and security), how should the Muslim community in general, and ulama in particular respond to the challenge of peace, order and security? Who or which sector do we need to work with and how? What should be our short-term and long-term priorities?

Point 6. Rasulullah SAW as our model

For the 1.6 billion Muslims in the world, Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) words and deeds in unison serve as the role model for us. In the Qur’an, he is viewed as “uswatun hasanah” (good model) in verse 21, chapter 33: Al Ahzab; as a “rahmah” (mercy) in verse 107, chapter 21: Al Anbiyah; that his example is not extreme and excessive, his model is not harshness and exclusion; and his message is love, not hate.

The challenge for ulama is how can they best promote the Sunnah of Rasulullah SAW as good model and mercy to the larger community?

Closing Statement

These are just six points highlighting the role, influence and often the untapped power of the Ulama in the Moro community. In closing, yes it should be noted that there is the general challenge of uniting Islamic altrusim with local reality. There is no question about the profundity of Islamic altruism. The question is how do we make the altruism a beginning reality in the Moro community, of respect for diversity within, in our relationship with non-Moro minorities within our community and the larger Filipino community and the world.

This is for the ulama to lead, to articulate and to model. Aleem Mujahid quoted a hadith that says, if two groups of people will be good, the rest of the community will be good. They are the ulama and the umara. We pray for our ulama and our umara. (MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Noor Saada is a Tausug of mixed ancestry – born in Jolo, Sulu, grew up in Tawi-tawi, studied in Zamboanga and worked in Davao, Makati and Cotabato. He is a development worker and peace advocate, former Assistant Regional Secretary of the Department of Education in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, currently working as an independent consultant and is a member of an insider-mediation group that aims to promote intra-Moro dialogue).

[1] [1] Sadullah Khan, “The Call of Islam: Peace and Moderation, Not Intolerance and Extremism” – http://www.islamicity.org/6258/the-call-of-islam-peace-and-moderation-not-intolerance-and-extremism/

[2] “The Wasatiyyah (Moderation) Concept in Islamic Epistemology: A Case Study of its Implementation in Malaysia” – http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_9_1_July_2014/7.pdf

[3] [1] Ahmed Khalili, “Dar Al-Islam And Dar Al-Harb: Its Definition and Significance” – http://en.islamway.net/article/8211/dar-al-islam-and-dar-al-harb-its-definition-and-significance

http://www.mindanews.com/mindaviews/2017/07/kissa-and-dawat-why-mobilize-the-ulama/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.