From MindaNews (Mar 20, 2021): The IP struggle continues as NCIP red-tags and bans use of “Lumad,” the collective word for Mindanao IPs since the late 1970s (By CAROLYN O. ARGUILLAS)

Lumad leaders and eminent Mindanawon scholars are questioning the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples’ (NCIP) resolution red-tagging and banning the use of “Lumad” to refer to Indigenous Peoples (IPs) in Mindanao, even as this Cebuano word has been used since the late 1970s as a collective term for at least 20 non-Moro IPs across southern Philippines.

‘Lumad’ means indigenous or native.

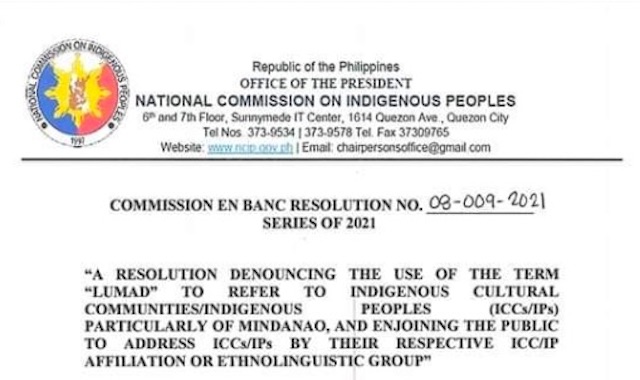

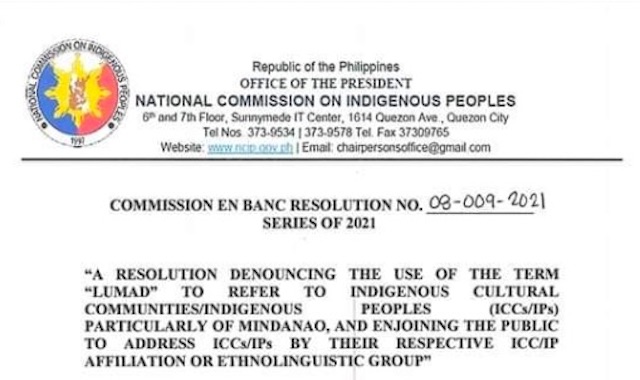

The NCIP en banc passed on March 2 Resolution 08-009-2021 “denouncing the use of the term ‘Lumad’ to refer to indigenous cultural communities / indigenous peoples (ICCs/IPs) particularly of Mindanao and enjoining the public to address ICCs/IPs by their respective ICC/IP affiliation or ethnolinguistic group.”

The NCIP claimed that the word’s “emergence and continued use is marred by its association with the CPP (Communist Party of the Philippines), NDF (National Democratic Front) and NPA (New Peoples’ Army) whose ideologies are not consistent with the cultures, practices and beliefs of ICCs/IPs.”

NCIP resolution on “Lumad”

It claimed that in looking at the historical context of how the term ‘lumad’ emerged, “it is but just and proper, to put order and in order to correct the injustice committed” by the CPP, NDF, NPA “and to put a stop to the corruption of the IP struggle,” that the NCIP “condemns and denounces the use of the term ‘lumad’ to refer to the ICC/IP groups of the Philippines and more particularly to the ICC/IPs of Mindanao.”

“Lumad,” however, refers only to the IPs of Mindanao, specifically, the non-Moro IPs.

The NCIP cited only one source in its presentation of the “historical context” of ‘Lumad,’ – Datu Lito Omos, who is active in the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), and who traces the etymology of “Lumad” to 1986.

“Lumad” as a collective word for non-Moro IPs in Mindanao was first used in the 1970s.

The NCIP resolution wants the public to stop using ‘Lumad’ to refer to Mindanao’s IPs but urged the public to “use the respective ethnolinguistic group or Indigenous Cultural Communities, Indigenous Peoples, Katutubong Pamayanang Kultural or Katutubong Pamayanan when referring to IPs collectively.”

‘Lumad’ is the shorter version of ‘Katawhang Lumad’ which literally means Indigenous Peoples.

Idiocy

Redemptorist Brother Karl Gaspar, a Mindanawon anthropologist, sociologist, theologian and artist, told MindaNews that when he first heard about the NCIP’s resolution’s red-tagging and banning the use of the word ‘Lumad,’ he didn’t know exactly how to react.

“I thought I would laugh at the idiocy of our public servants in the NCIP who are mandated to serve our indigenous communities,” Gaspar said.

“At one level, kataw-anan gyod! (it’s really funny). I even thought morag nabuang na man ning mga taga-NCIP oy (the NCIP is acting like crazy). However, this is no laughing matter for it shows us how seriously misinformed the NCIP powers-that-be are in terms of the history of the Lumad Social Movement in Mindanao. One can even refer to them as ignoramus for not having checked available secondary literature, so that their move would have scholarly basis,” he said.

Gaspar wrote “The Lumad Social Movement” for a course under Professor Prospero Covar, acknowledged one of the pillars of Philippine Anthropology, while pursuing his PhD in Philippine Studies at the University of the Philippines in the late 1990s and having been a church worker since the 1970s, “I could claim to have a privileged historical view of how the term Lumad arose.” The essay was first published by the Alternative Forum for Research in Mindanao in 1997 and re-published in Aninaw, the journal of the Ateneo Institute of Anthropology at the Ateneo de Davao University in 2018.

Redemptorist Brother Karl Gaspar answers questions during the open forum of the ‘Civil Society Conversations on Democracy and Information” on August 23, 2019 at the Ateneo de Davao University. MindaNews photo by GREGORIO BUENO

He is also the author of several books on Lumads, including ‘Manobo Dreams in Arakan: A People’s Struggle to Keep Their Homeland” which won the 2012 National Book Award for Social Sciences,

Gaspar told MindaNews that when he realized that the NCIP was “taking this whole issue seriously and other branches of the State apparatus joined in the chorus to ban the word Lumad, I then realized how the anti-terror law is claiming more and more victims. This time, not just human persons are red-tagged, but innocent words like Lumad can also be red-tagged.”

He asked: “are we seeing the unfolding of a State that will now decide for us as to the vocabulary that we can use in referring to various individuals, groups, institutions? And if they succeed in demonizing the word Lumad, what other words will also be red-tagged? And if this is no longer enough for their counter-insurgency drive to succeed, is the next move to burn books where words like Lumad appear?”

Gaspar also noted that at various historical junctures not just in this country but in many other nation-states throughout the world, “red-tagging has resulted in the deaths of innocent civilians and the untold suffering of communities victimized by this red scare.”

“Profusely used”

The NCIP said “Lumad” has been “profusely used” by government offices, public officials and the public. President Rodrigo Duterte, who hails from Mindanao, even posed holding a sheet of paper marked with the message “Stop Lumad Killings” in September 2015, while still mayor of Davao City. As President, he also refers to IPs in Mindanao as Lumads.

The NCIP resolution claimed the word ‘Lumad’ was adopted by members of the Lumad Mindanao Peoples Foundation (LMPF) on June 26, 1986 during its founding congress in Kidapawan, North Cotabato and that “an ensuing meeting of the LMPF was conducted at the University of San Carlos in Talamban, Cebu to lay down the framework to use the term ‘lumad.’ From then on, the term gained popularity and was widely used to refer to ICCs/IPs.”

The NCIP resolution also claimed that the founding congress and subsequent meetings and activities of the LMPF “were initiated and sponsored” by the CPP, NDF, NPA.

There is no foundation named Lumad Mindanao Peoples Foundation. There was a LUMAD-Mindanao, a Lumad Mindanaw, and a Lumad Mindanaw Peoples Federation which, according to Jimid Mansayagan, chair of its Governing Council, was founded in September 1994 as a “genuine indigenous peoples organization with vision of asserting the inherent inalienable and collective rights to identity, land territory, self-determination and self-governance.”

The NCIP erred not only in the spelling, name of their federation and date of founding but also in claiming that the LMPF is the handiwork of the left, Mansayagan said, adding the LMPF in fact was a product of the Lumad leaders’ renunciation of alliance with the left.

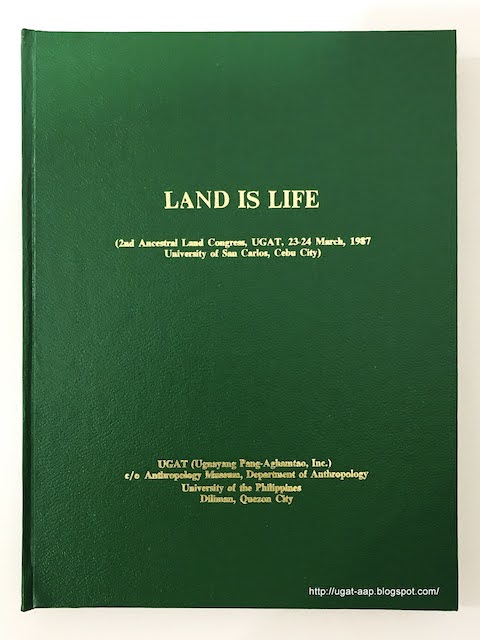

Land is Life

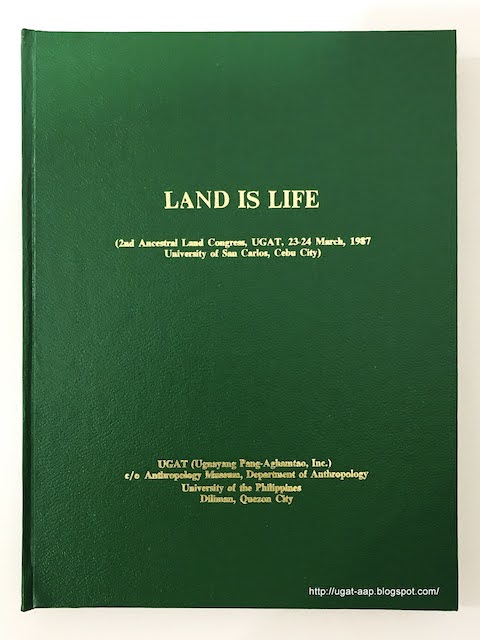

The University of San Carlos meeting that the NCIP resolution referred to was actually the 2nd Land Congress on March 23 to 24, 1987, whose theme was “Land is Life.”

Mindanawon anthropologist Maricel Hilario-Patiño, told MindaNews that the Land Congress, was actually a follow-through of the policy consultation workshop called for by then Environment Secretary Carlos Dominguez (now Finance Secretary) and attended by representatives of the Ungnayang Pang-aghamtao (UGAT or the Anthropological Association in the Philippines), along with “technocrats, professionals, academicians, big business concessioners, etc. in January 1987.”

Cover of the Proceedings of the 2nd Land Congress, March 1987.

The Land Congress in March was attended by “250 participants from 20 tribal organizations 10 support organizations and six representatives from the government sector” and among the personalities present were UGAT Founding President and 1986 Constitutional Commissioner Ponciano Bennagen; Agusan del Sur OIC Governor Ceferino Paredes and his Provincial Attorney, Roan Libarios, Gregorio Andolana, then Representative-elect of North Cotabato, Prof. Owen Lynch, Fausto Lingating, Deputy Minister of the Office of Muslim Affairs and Cultural Communities and chair of the Consultative Assembly of Minority Peoples of the Philippines; and representatives of various offices and the Policy Advisory Group of the DENR.

Omos in a press conference of the NTF-ELCAC said he was in this Congress and that UGAT convened the meeting.

What was discussed were the issues on ancestral lands and ancestral domains affecting not only the Lumads in Mindanao but also the other IPs nationwide. The Congress was held just a month after the 1987 Constitution, which now vowed to address the historical injustices against the IPs nationwide, was ratified in a plebiscite.

The Land Congress was funded by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources through Secretary Dominguez, The Asia Foundation, SVD Provincialate, SSPS Cebu Communities, Episcopal Commission on Tribal Filipinos and University of San Carlos while the manuscript of the proceedings was printed courtesy of the Office for Southern Cultural Communities.

Hilario–Patiño said that among the highlights of the Congress was the validation of the proposed Executive Order Creating the Commission on Ancestral Domain.

“Many leaders I have talked to described that this was the first draft of IPRA (Indigenous Peoples Rights Act),” but she quoted Bennagen as saying that when this was submitted to President Aquino she said she would rather that it would pass through Congress because issuing Executive Orders is “like a Marcosian move.”

It took 10 years before Congress passed IPRA.

‘Bisaya’ as lingua franca

How “Lumad” became the collective term for non-Moro IPs in Mindanao, is traced to the late 1970s within the circles of the Catholic and Protestant churches with ministries for the IPs. Another version traces it to a 1986 assembly in Kidapawan, North Cotabato during the founding Congress of Lumad Mindanaw.

In both versions, however, the decision to use “Lumad” was reached by the IPs themselves, because while they came from various ethnic groups in Mindanao and spoke different languages, they could communicate with each other using Cebuano or what in Mindanao is commonly referred to as ‘Bisaya.’

“Lumad” was intended to distinguish them from the Moro who are also indigenous to Mindanao, and from the ‘Bisaya’ which had earlier become a generic word for “settler.”

For a time, Mindanao was referred to as “tri-people,” comprising the indigenous Moro and Lumad, and the settler population.

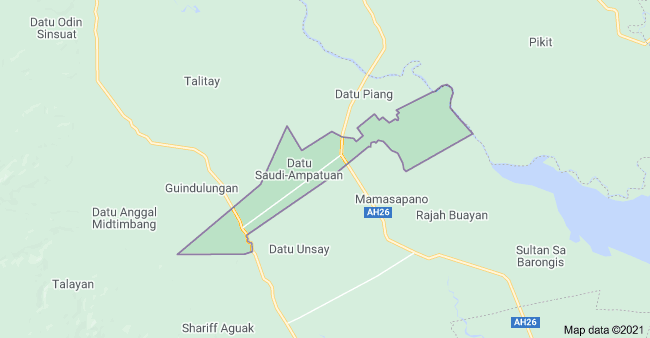

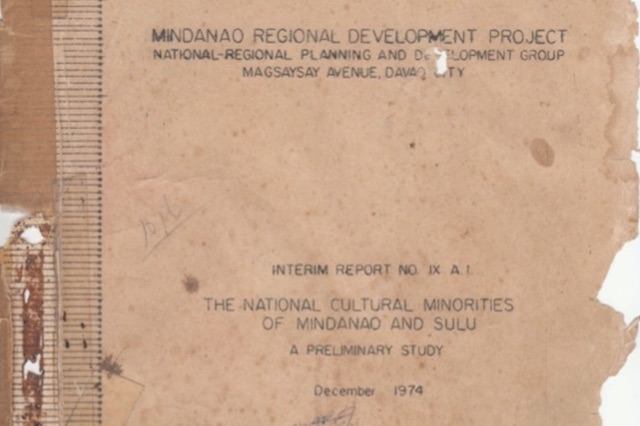

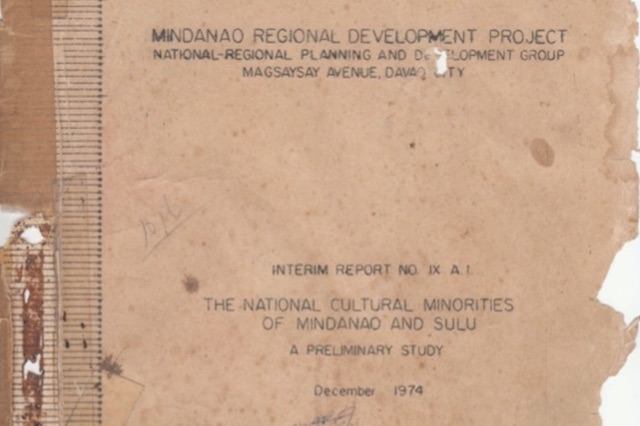

The National Cultural Minorities of Mindanao and Sulu: A Preliminary Study, 1974.

Historian Rudy Rodil recalls that as team leader in 1974 for a Study on the National Cultural Minorities of Mindanao under the Mindanao Regional Development Project of the Mindanao Development Administration, he learned that when leaders from various tribes meet, “automatic nga Bisaya ang lingua franca” because “diha lang sila magkasinabot” (they would automatically speak in Bisaya because that is the only way they could understand each other).

He said all their field interviews in the IP areas were in Bisaya. He recalled that even in the meeting of the Mindanao Highlanders Association or Mindahila, an organization of IP leaders, Bisaya was also the language used.

“Lumad” in the 1970s

In the 1970s, the use of the word ‘Lumad’ to refer to IPs in Mindanao started taking root during a series of conferences initiated by Catholic and Protestant churches in Mindanao with IP leaders. Note that this was a period under martial law and among those who suffered human rights violations were the Moro and IPs of Mindanao.

Martial law, however, was just part of the long-running problem of Moro and IPs in Mindanao who were marginalized and minoritized during the Spanish and American regimes and later by the Manila-based central government. For decades starting with the agricultural colonies set up in 1913, residents from the Visayas and Luzon were enticed to settle in resource-rich Mindanao, then being touted as “Land of Promise.” Part of the enticement were land policies favoring wave after wave of migrants.

Soon thereafter, Mindanao was opened up for plantations, logging, mining and fishing operations, displacing thousands of Lumad and Moro peoples.

The Mindanao church – both Catholic and Protestant – was active in fighting for the rights of Mindanao’s IPs.

Among those at the forefront in advocating IP rights was Bishop Francisco Claver, an IP himself from Northern Luzon who was Prelate Ordinary when the Prelature of Malaybalay was established in 1969 and its first Bishop when it became a Diocese in 1982; Mindanao’s other bishops, priests and nuns, including foreign missionaries assigned to Mindanao for several years, and church workers.

Various church formations were also set up, in the 1970s including the Mindanao–Sulu Secretariat of Social Action (MISSSA), the secretariat for all Social Action Centers of the Archdioceses, Dioceses and Prelatures of Mindanao.

The MISSSA convened the First Mindanao Regional Conference on Cultural Communities in Lake Sebu, Surallah, South Cotabato on February 5-7, 1974 “to give voice to the Mindanao minorities… a voice of anguish, frustration and fear; a voice crying out, almost without hope, appealing to the Christian communities of Mindanao.”

Exactly when the word ‘Lumad’ evolved into a collective term for non-Moro IPs in Mindanao cannot be ascertained but based on documents gathered by MindaNews and interviews with personalities who were active in church work in the 1970s, it was in the latter part of the decade.

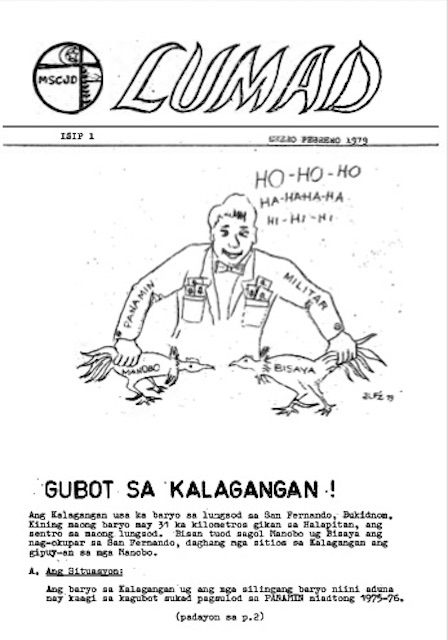

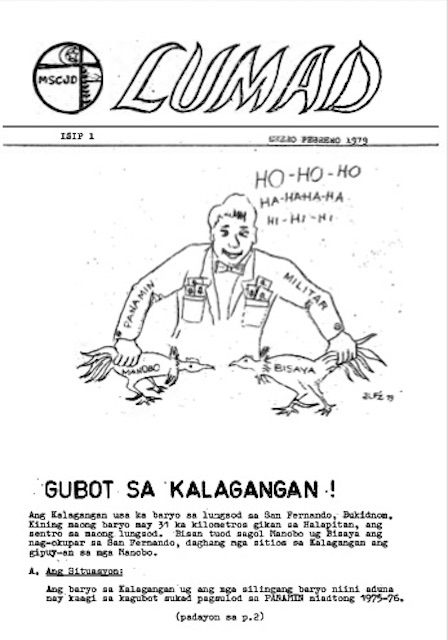

Lumad newsletter, 1st issue, Jnauary-February 1979.

There was even a newsletter named ‘Lumad,’ a publication of the Mindanao-Sulu Conference on Justice and Development (MSCJD) which Claver chaired. The publication focused on IP issues. Written in ‘Bisaya,’ its first issue was January-February 1979 and among the articles was a report on a Regional Consultation on December 18 to 22, 1978 in Midsayap, North Cotabato.

“Pahayag sa mga Lumad”

A seven-paragraph “Pahayag sa mga Lumad” (Declaration of the Lumads) dated December 21, 1978, crafted during that conference, was also included in the newsletter.

The declaration asked “Kinsa kami” (who are we) and “Unsay nahitabo” (what is happening to us) and “Ngano nga naghimo kami niining pahayag?” (why are we making this declaration?)

Responding to their own query on who they are, the Declaration said: “Kami ang mga lumad sa Mindanao sama sa (We are the Lumads of Mindanao such as the) Manobo, Subanon, Tiruray, B’laan, Higa-ono, Tagabawa” who gathered in Midsayap for the assembly called for by the National Council of Churches in the Philippines and the MSCJD, to share experiences on problems affecting their communities in Mindanao, analyze their situation and plan on how to address these issues.

The participants said they made the declaration because of the spate of human rights violations that they experienced, including oppression, discrimination, harassment and trampling of their rights as “lumad sa Mindanao” (Lumads of Mindanao).

The declaration said they hope government, the church and other groups would attend to them so their communities can thrive and they can live in peace.

Pop culture

Beyond the church and Lumad communities, the use of “Lumad” to refer to IPs became so popular it encouraged migrants who settled in Mindanao to want to learn more about the Lumads and their cultures. There was a surge in pride of being “Lumad,” too, as they were now given platforms where they could speak up and share their music and dances, among others.

Going “Lumad” became the “in” thing. Nieva’s Crafts, a Davao City-based business enterprise, launched its “Lumad” brand in 1981 featuring ethnic designs.

CD cover for Joey Ayala and Bagong Lumad’s “Mga Awit ng Tanod Lupa.”

Singer-composer-poet Joey Ayala, now a nominee for National Artist, told MindaNews he coined the term “Bagong Lumad” (literally ‘new native’) around 1980-1981” while still based in Davao City and used it “in the mid-1980s for a show at UP with Patatag.” He said the band “Bagong Lumad” was formed around 1985 to 1986.

Ayala also founded Bagong Lumad Artists Foundation, Inc. in 1988 to, among others, “reawaken indigenous consciousness.”

The Lumads were also featured in Noe’s Ark shirts designed by the late graphic artist Noe Tio, who was drummer of Bagong Lumad.

LUMAD-Mindanao

Mansayagan recalls that in 1983, a multisectoral organization named LUMAD-Mindanao was established with lawyer Fausto Lingating, a Subanen from Lapuyan, Zamboanga del Sur, as founding chair. LUMAD meant Lumadnong Alyansa alang sa Demokrasya.

On April 2, 1985, human rights lawyer Romfraflo Taojo, then chair of LUMAD-Mindanao, was gunned down in his apartment in what is now Tagum City in Davao del Norte.

Mansayagan said an assembly was held in August 1985 supposedly to choose Taojo’s successor but choosing a successor proved to be difficult as many feared they would end up like Taojo. In May 1985, a month after Taojo’s murder, three human rights lawyers in Davao City – Laurente Ilagan, Antonio Arellano and Marcos Risonar — were arrested on the strength of a Preventive Detention Action.

But it was in this August 1985 conference, Mansayagan said, where the IP leaders asserted they wanted a “pure Lumad” organization.

The non-Lumad in the assembly, he said, formed the support group, KADUMA-Lumad or Kahugpugan sa mga Dumadapig ug Nakig-unong sa Lumad while an Ad Hoc Committee composed of Lumad leaders from different parts of Mindanao was formed for the “pure Lumad” organization.

By first week of November 1985, President Ferdinand Marcos, who had by then overstayed his term of office by 12 years (he declared martial law on September 21, 1972; his second and last term as President was supposed to have ended on December 30, 1973), announced in an interview with America’s David Brinkley that he was calling for snap elections on February 7, 1986.

1986 Assembly

The dictator Marcos was ousted and Corazon Aquino, widow of the assassinated former Senator Benigno Aquino, was sworn in as President on February 25, 1986.

In June 1986, Mansayagan, then 26, said, the founding assembly of the “pure Lumad” organization – Lumad Mindanaw – was held in Kidapawan City.

There, he said, IP leaders discussed the many issues they were facing and towards the end of the assembly, discussed the appropriate word that would collectively refer to the different ethnic groups in Mindanao who are not Moro.

The consensus of the IP leaders, he said, was “Katawhang Lumad” which is ‘Bisaya’ for Indigenous Peoples. The founding chair, he said, was Datu Balitungtong Antonio Lumandong, a Higaonon from Misamis Oriental. Omos, a Mangguangan from Davao del Norte, was its Secretary-General in the first two years.

Mansayagan said that in July 1987, Omos was the first Lumad who attended the sessions of the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Peoples and that is how “Lumad Peoples” was first recorded in the United Nations as, according to Mansayagan, “the identity of Mindanao un-Islamized indigenous population.”

Rodil was present at the assembly at the Guadalupe Formation Center on June 26, 1986 as a resource person on Mindanao history. He was then a Professor at the Mindanao State University – Iligan Institute of Technology in Iligan City and he recalls listening to the exchanges of the IP leaders on the collective name and the word “Lumad” won.

The historian remembers it was Fr. Rodulfo ‘Dong’ Galenzoga, who facilitated the discussion. MindaNews e-mailed the priest early Sunday morning to ask him about what he remembers of that meeting. He succumbed to pneumonia noon that day in a hospital in Iligan City.

Mansayagan recalls it was a long discussion initially facilitated by Nestor Masinaring and later by Galenzoga.

Rodil said that during this meeting, “wala ko nakadungog ug NPA or LMPF. Isip historian mao ang akong gigamit sa akong libro ug sa tanan nakong public lectures. Historic kato, first time nga nakasabot sa collective name sa mga Lumad. Simple ang meaning, indigenous, native, nitibo, taga Mindanaw ug lahi sa mga Moro or Bangsamoro” (I heard nothing of the NPA or the LMPF. As a historian, I used the word ‘Lumad’ in my books and all my public lectures. It was historic, first time the IPs agreed on a collective name with a simple meaning, indigenous, native, from Mindanao and distinct from the Moro).

Here was a collective name that the Lumads themselves did not find pejorative unlike the collective names given them by the Spaniards, Americans and even by the national government.

Rodil said the Lumads were described by the Spaniards as “paganos,” by the Americans as “Wild Tribes” or “Uncivilized Tribes” or “Non-Christian Tribes;” by the national government as “National Cultural Minorities,” “Cultural Minorities,” or “Minorities.” In the 1973 Constitution, the IPs nationwide were referred to as Cultural Communities and in the 1987 Constitution as “Indigenous Cultural Communities.”

Common term

Italian-American missionary Peter Geremia, PIME, who headed the IP Apostolate in the Diocese of Kidapawan for decades, recalls that in the early 1980’s when they had consultations with the IPs in the Diocese of Kidapawan “we asked them if they have a common term for all tribes in Mindanao. They replied that they used the term of each tribe like Manobo, B’laan, etc.”

He said a common term was proposed: “Talaingod and therefore, the first organization including different tribes was called NAKATA or Nagkahiusang Katawhang Talaingod.”

But Geremia noted that the term “Talaingod” was not widely used.

“The Bisaya used the term ‘Lumad’ for all tribes in Mindanao” but when the Diocese organized the Tribal Filipino Program, they preferred the term ‘Tribal Filipino,’ he said.

“Some Tribal Leaders did not like the term ‘Lumad’ but it was widely used also by many Tribals,” Geremia told MindaNews on Tuesday.

He remembers the assembly in Kidapawan in 1986 when Lumad Mindanaw was born “but I do not remember if there were objections to the term ‘Lumad.’ I never heard that the term ‘Lumad’ was initiated or sponsored by the CPP-NPA-NDF, I only heard that it was the common term used by the Bisaya.”

Geremia recalled that some Lumad Mindanaw leaders were later “tagged leftist or sympathizers of the NPA.”

Mansayagan said “Lumad Mindanaw” died on the day Lumad Mindanaw Peoples Federation was born in September 1994, during the general assembly of Lumad Mindanaw in Alabel, Sarangani where they also renounced alliance with the left.

“The end of Lumad Mindanaw was the beginning of LMPF,” he said, adding that they restructured the organization into a “genuine indigenous peoples organization with vision of asserting the inherent, alienable and collective rights to identity and / territory, self-determination and self-governance.”

He said they have identified about 30 groups of “Katawhang Lumad” (Indigenous Peoples) in Mindanao who are asserting their rights to identity, ancestral domains and self-determination.

“Ridiculous”

Anthropologist Gus Gatmaytan, Director of the Ateneo de Davao University’s Institute of Anthropology described the NCIP resolution as “ridiculous.”

Gatmaytan said “Lumad” was adopted in the 1980s by Lumad leaders from different parts of Mindanao “who realized that they had shared or common experiences of insecurity, dispossession and violence during the years of Marcos’ Martial Law regime, and that they now needed a collective name that would refer to them as a group, and distinguish them from the Moro and settler populations of Mindanao.”

Gatmaytan stressed that the use of ‘Lumad’ as a collective term for IPs of Mindanao does not contradict the fact that they have their own ethnic names for themselves. “Identity is a complex and relational concept and process that allows a person to be an individual, an Arumanen Manobo, a Lumad, and a Filipino, depending on the context and their will,” he said.

Right to self-ascription, self-determination

Gatmaytan said it can be argued that “the gradual adoption of the name Lumad is an agentive act on the part of the various groups in Mindanao, reflecting a realization that as a group they had similar histories, problems and aspirations, which together serve as the basis for a shared sense of identity; an identity which they chose to refer to as Lumad.”

Their continuing use of the name Lumad, he added, is “an exercise of their right to self-ascription, which is itself rooted in their fundamental right to self-determination.”

Talaandig elders prepare chickens for sacrifice during the ritual to commemorate the 10th year of the Moro-IP Friendship in Songco, Lantapan town, Bukidnon on Monday, 8 March 2021. MindaNews photo by FROILAN GALLARDO

“To say that the indigenous people of Mindanao were somehow manipulated into using the term Lumad, as the NCIP seems to be saying, is to assert that they are merely gullible minions of outsiders, incapable of understanding who they are, what they need and want, and planning their future,” he said.

Gatmaytan explained that if the IPs, groups, communities or individuals choose to refer to themselves as Lumad, “then that is their inherent and inalienable right.”

“No one — not the NCIP nor the Philippine state — can gainsay their decision to do so; nor can anyone ‘ban’ their use of any name they choose to use. The NCIP should need no reminder to honor and respect the indigenous peoples’ exercise of their right to their identities, and to denote their identities in any manner or with whatever name they want. It should refrain from any further attempt to politicize and control indigenous identity, and instead focus on the many, more urgent concerns and issues that the indigenous peoples face,” he said.

Focus on “bigger issue”

Gaspar said the use of “Lumad” to refer to IPs “did not arise out of an ideological movement for an ideological reason. And as befits the origin of words that become part of a lexicon of a social movement, one cannot trace anymore where it first arose and who made the first move to start using the word. Somehow in the course of time, the word got appropriated and eventually took on a meaning for those using the term within the world of meaning for which it arose. And now an agency of a dictatorial State apparatus would claim the right to determine its origin? What an idiotic thing to do!!!”

Marites “Matet” Gonzalo, a Tagakolu anthropologist from Davao Occidental who serves as Coordinator of the two community-based IP schools of the Malita Tagakaulo Mission — the Holy Cross of Malita’s Kyasan and Lebleb branches — told MindaNews on Thursday that they have no issue with the word “Lumad” because they use the term “referring to ourselves” when they talk to those outside their communities.

A Lumad evacuee from Barangay Diatagon in Lianga, Surigao del Sur and her baby at the provincial sports complex in Tandag City on Oct. 1, 2015. MindaNews file photo by H. MARCOS C. MORDENO

Gonzalo said the Church has an “Adlaw sa Lumad” or IP Sunday or what was earlier known as Tribal Filipino Sunday. She said they also have a Lumadnong Katesismo or Indigenous Catechesis and even have a song about their being Lumad like “Kitadun tengteng Lumad” or “We are Lumads.”

The word ‘Lumad,’ Gonzalo said, is not the issue. The bigger issue that needs to be addressed, she said, is the situation of the Lumads who are “pirming maipit ug magamit sa left and right nga grupo” (who are always the ones victimized and abused by groups from the left and right). (Carolyn O. Arguillas / MindaNews)

https://www.mindanews.com/top-stories/2021/03/the-ip-struggle-continues-as-ncip-red-tags-and-bans-use-of-lumad-the-collective-word-for-mindanao-ips-since-the-late-1970s/