Posted to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) (Jun 22, 2023): Special Issue: Violence Targeting Local Officials//The Philippines// Rivalries Between Local Elite in The Philippines Fuel Violence (By Tomas Buenaventura)

The Philippines has historically grappled with a high level of violence targeting local administration officials, particularly in relation to electoral competition between local elite families. The high-profile assassination of Negros Oriental Governor Roel Degamo in March 2023 is a recent example that illustrates this phenomenon.1 However, such violence has long persisted in the Philippine countryside. The most notorious example is the Maguindanao Massacre of November 2009, in which 58 people were killed in an attack masterminded by members of the Ampatuan clan against their rival Mangudadatu family.2 The attack is also thought to be the most lethal assault on the press in contemporary history, as 32 journalists were among those killed.3 The massacre took the lives of several members of the Mangudadatu family during an election-related event, including a vice mayor and other relatives of a Mangudadatu scion set to run against an Ampatuan for governor.4

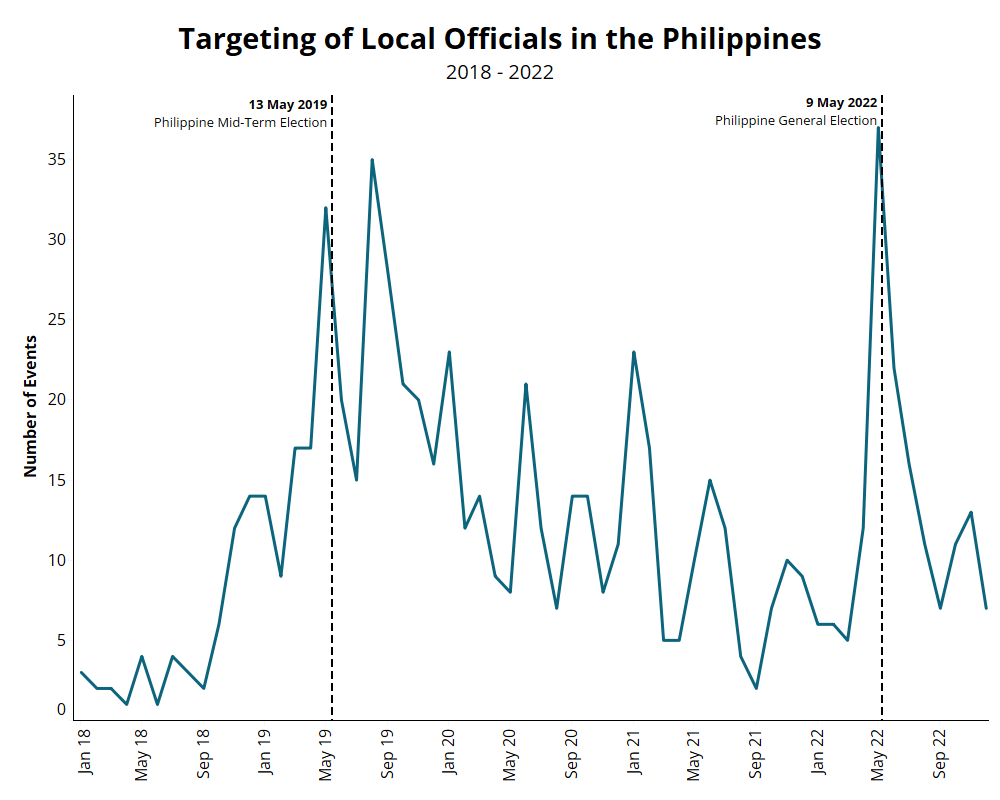

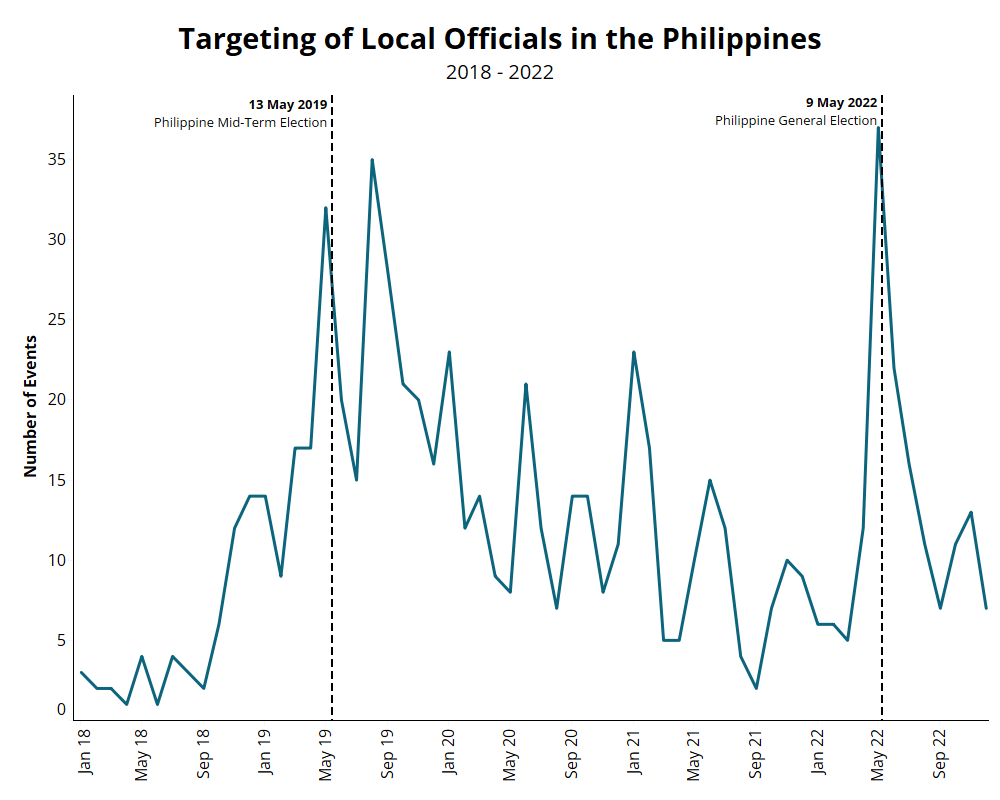

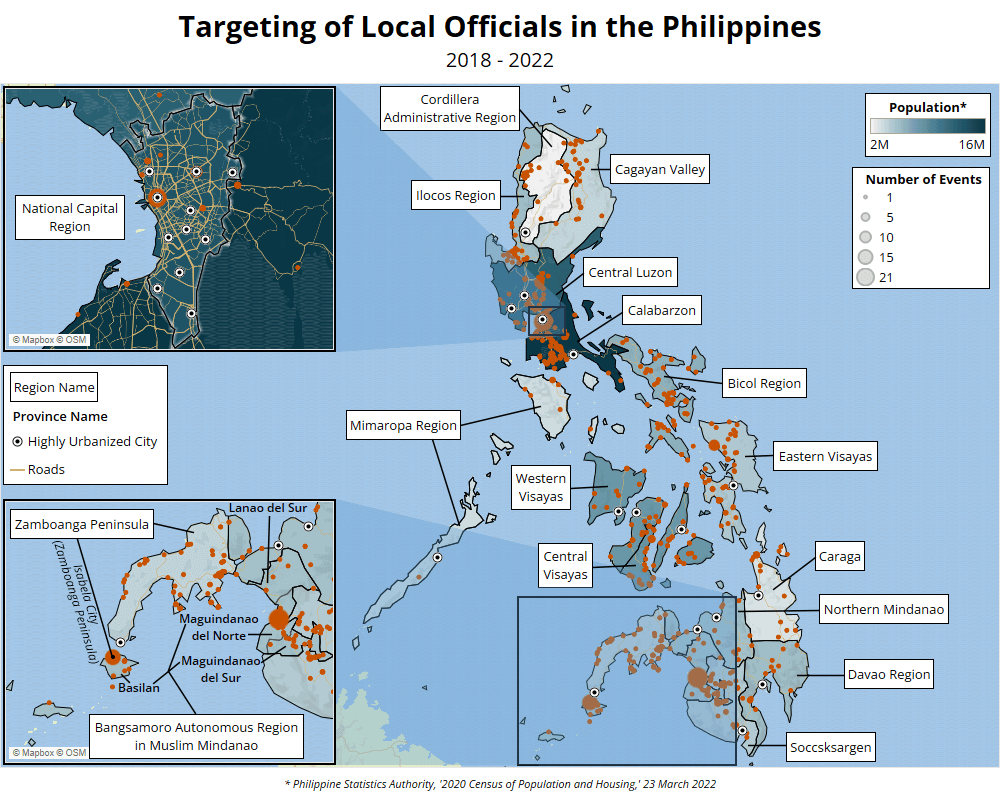

These examples reflect the brazen nature of such violence. However, its prevalence is equally alarming: ACLED records 716 acts of violence against local officials between 2018 and 2022. Such violence is heavily concentrated in rural areas, particularly in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), and especially during election periods. ACLED data show notable spikes of violent events targeting local government officials during the May 2019 midterm and May 2022 general elections, with BARMM, particularly the Maguindanao provinces, accounting for a disproportionately high amount of such targeting.

BARMM, like other rural areas that see elevated levels of such violence, is marked by conflict and characterized by a devolved political system, the proliferation of political dynasties, and the domination of ‘strong families’ who find recourse in violence to secure their interests. This report examines the temporal and subnational patterns seen in the targeting of local officials in the Philippines.

Electoral Violence Driven by Hired Unidentified Assailants

While the Philippines is home to many conflicts, including the communist insurgency as well as the Moro separatist struggle in Mindanao, a large percentage of the violence targeting local officials occurs outside of such conflicts. Many attacks occur without clear motives identified in media reports. ACLED data show 79% of violence targeting local government members between 2018 and 2022 was committed by unidentified actors. While the identity of those who carry out such violence is often unknown, much of this violence is thought to be committed by hired killers acting at the behest of local political players, and also possibly by members of private armed groups associated with political families.5 Peace Research Institute Frankfurt Professor Peter Kreuzer found that political players are more likely to engage hired guns for one-off or rare operations, rather than utilizing a private army that might be better known to law enforcement and thus easier to connect to the mastermind. As such, Kreuzer notes that “in the vast majority of cases it cannot be proven who actually ordered the killings.”6

Political competition drives spikes in the targeting of local officials in the Philippines, as evidenced by increases in such violence during election seasons.7 ACLED data show a significant increase in the targeting of local officials around midterm elections in May 2019 and around presidential elections in May 2022 that saw the transition from President Rodrigo Duterte to new President Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos, Jr. (see figure below). Over 30 such violent events were seen in May 2019, followed by an even higher peak of nearly 35 events in August 2019, fresh into the election winners’ new terms. The May 2022 election period was even more violent, with over 35 violent events targeting local officials during that election month alone.

This electoral violence is partly driven by electoral competition between political dynasties. The Philippine political landscape is characterized by the proliferation of political dynasties, as well as the system of political patronage they depend on for survival. Political dynasties, or the capture of multiple or successive elective posts by members of the same family, are technically banned by the Philippine 1987 Constitution. However, this ban has not been operationalized due to the lack of a required enabling law8 – one that has a poor chance of passing in a House of Representatives dominated by political dynasties.9 As of 2016, 78% of the members of the House of Representatives were part of political dynasties.10

The 2019 attack on Amado Espino, Jr., a former governor and representative of Pangasinan province in the Ilocos Region, is a typical example of such violence involving political dynasties. Espino is the patriarch of a powerful clan that has seen several members in top elected positions, such as his son who was then the incumbent governor. In an ambush on 11 September 2019, assailants injured Espino and killed a police officer serving as Espino’s aide. Hired assailants, including a former scout ranger from the Philippine Army, perpetrated the ambush.11

Police investigators later identified the attack’s mastermind as Raul Sison, a provincial board member from a smaller political dynasty whose son was also serving as a town mayor. The alleged mastermind died due to COVID-19 in March 2020 and the motive for the attack is still unclear.12 Nonetheless, Sison was described in a media report as a ‘deserter’ of the Espino camp, which was engaged in fierce electoral battles.13 Espino again ran for governor in 2022, though he lost in an upset.14

These dynamics in local politics have led some observers of Philippine society to note the outsized impact of ‘strong families,’ representing a dominant oligarchic class who thrive on political patronage vis-à-vis the ineffectual presence of the so-called ‘weak state’ in their localities.15 Such a reality, coupled with the weakness of political parties in the Philippines, also means families play an outsized role in the political landscape, taking on the role played by parties in other contexts as vectors for political movement.16 When multiple oligarchic families find themselves competing for the same set of elective posts, all promising access to lucrative local budgets and discretionary funds, some end up finding recourse in political violence to secure desired political outcomes. This phenomenon was referred to by Kreuzer as ‘violent self-help,’ which appears to have been accepted as a political reality in certain settings in the Philippines.17 The prevalence of violent self-help among political families collapses the lines separating the institutional and personal, whereby extra-institutional means are used to secure the dynasty’s hold on power.

Further, recent research into the impact of political dynasties on Philippine society shows that political violence is a manifestation of both political and socioeconomic inequality. In areas outside the capital Manila and the main island of Luzon, which enjoy greater distance from close institutional surveillance, the persistence of political dynasties is associated with greater poverty.18 Such areas are commonly dominated by local ‘bosses’ who seize control over an area’s resources, partly through coercion and partly through institutional legal means.19

The poverty in these areas has helped generate a prevalence of actors willing to take up political violence. However, it is not just dejected, impoverished citizens who turn toward violence as an appealing alternative to their current reality. Rather, segments of the elite, usually dynastic political families, try to secure their interests by actively turning toward such actors to do their bidding.20 The concentration of political violence in areas far removed from national centers of power is, thus, a sign of the weakness of institutions and inadequately established government accountability.

Local Officials in BARMM at Higher Risk

The targeting of local officials in the Philippines is concentrated mostly in rural areas. ACLED data show that between 2018 and 2022, just under 86% of events tagged in the ACLED data set as violence targeting local officials occurred in rural areas. For the purposes of this report, rural areas are defined as all areas in the Philippines outside of 33 cities described as “highly urbanized” in the 2020 census, which include 16 cities in the National Capital Region (NCR) and 17 cities outside the NCR.21

The prevalence of this phenomenon in the Philippines, particularly in rural areas, is rooted in certain rural dynamics that facilitate an easy recourse to political violence. One relevant characteristic of the rural Philippines is the power and influence of local politicians in charge of and competing for positions in the local government unit. Such power and influence derive largely from a decades-long governmental push toward devolution. This process was definitively ignited by the enactment of the Local Government Code of 1991, which delegated most basic governmental functions and services to the different levels of local government.22

Violence is often seen in the very lowest levels of Philippine governance. ACLED data show that a significant portion of violence targeting local authorities is committed against officials in barangays (sub-city or sub-town districts), such as barangay chairpersons and barangay councilors. A smaller number of attacks concern other local administrative positions – from the municipal or city levels, all the way to the provincial level.

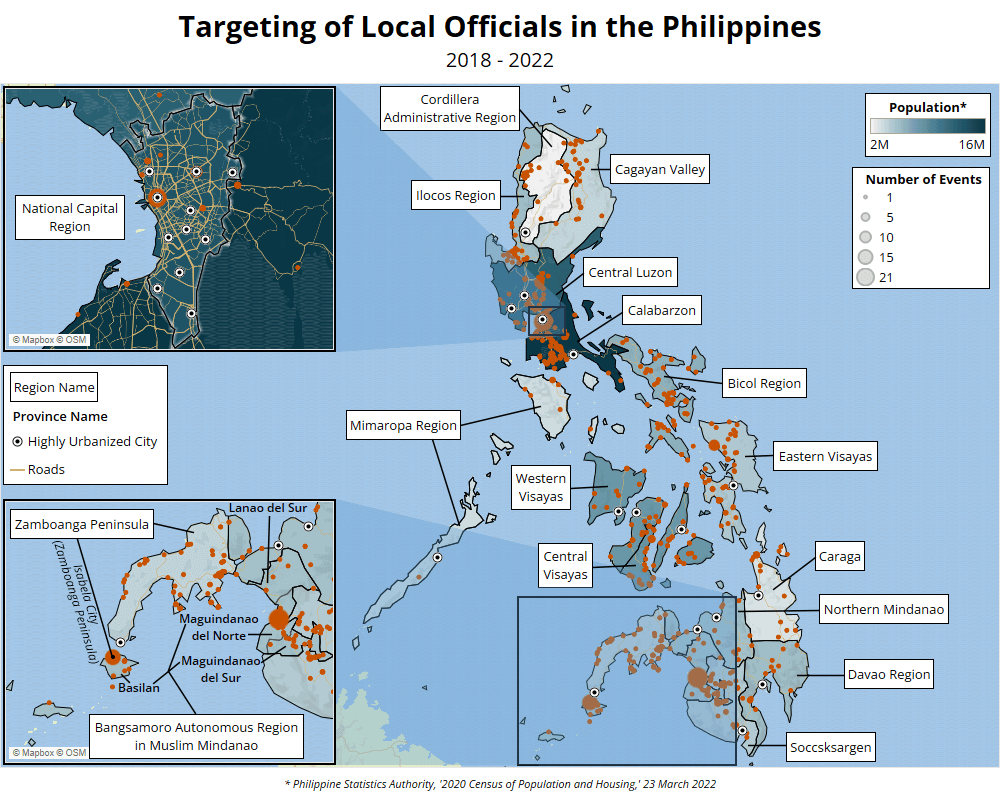

The geographical patterns of violence against local officials largely track with the general population of the country. As such, the eight regions comprising the country’s largest island group of Luzon – home to nearly 60% of the country’s population – make up the largest share of violent events against local officials between 2018 and 2022. Mindanao and the Visayas followed. However, some regions have a disproportionately higher share of such violence relative to their population, particularly the BARMM. While BARMM falls in the middle of the pack in terms of its national population share, at 4%,23 it sees the second highest number of violent events against local officials between 2018 and 2022 (see map below). Slightly over 10% of violence targeting local officials occurred in BARMM, trailing only slightly behind Calabarzon – the country’s most populous region – at nearly 11%.

Within BARMM, the two Maguindanao provinces comprised nearly three-fourths of all violent events targeting local officials between 2018 and 2022. Maguindanao del Norte saw 44% of such violent events in the region, while Maguindanao del Sur recorded 32%. Lanao del Sur and Basilan (excluding Isabela City, which is not part of BARMM as per the 2019 Bangsamoro plebiscite) also see elevated levels of violence.

The intersection of multiple issues characterizes the situation in BARMM. In particular, the Maguindanao provinces – a single province until a 2022 referendum – are beset by rivalries between dynastic families caught in rido, a term for clan feuds in BARMM.24 These deeply rooted disputes extend from issues over land, to the contestation of political positions. In rido-related disputes, militias affiliated with rival clans sometimes engage in clashes, or carry out attacks against the rival clan, in some cases leading to the deaths of prominent rival clan members, including those working in local government. Such conflict occurs amid a difficult security landscape defined by the presence of armed groups, such as the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and Islamic State-inspired breakaways, such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters. A telling manifestation of this interplay between preexisting local conflict dynamics and violence targeting local officials is the fact that the masterminds behind the Maguindanao Massacre of 2009 initially tried to pass the blame on to the MILF.25

Notably, data from the 2019 midterm elections show that the former single Maguindanao province also had the highest national rank in terms of the share of ‘fat dynasties,’ defined as families with two or more members in elected office. There, 51% of elected posts were occupied by members of fat dynasties.26 In this context, where actors from different conflicts often associate with powerful families and vice versa, and where ongoing issues have generated an abundance of firearms,27 fighting can involve the killing of local officials who happen to be an obstacle to the interests of a local boss.

Violent Recourse for Elite Interests

Violence against local officials in the Philippines is a multifaceted issue, reflecting long-standing, historically rooted political and socioeconomic realities. Other ongoing issues of political violence in the Philippines also influence the way such realities play out, therefore comprising a complex web of political violence in the country. This political violence was recently again dramatically brought to the spotlight through the aforementioned killing of Negros Oriental Governor Degamo on 4 March 2023. The incident, which followed a high-profile electoral dispute, again illustrated some common aspects of such events: hired killers carrying out an operation after allegedly being contracted by members of a rival political family.

Degamo had faced off in the Negros Oriental gubernatorial race in May 2022 against a member of the powerful, dynastic Teves family, whose dominance in Negros Oriental resembles the Espinos’ position in Pangasinan. While Pryde Henry Teves was initially declared the winner in that May 2022 race, the Commission on Elections later nullified his win after ruling that thousands of additional votes were rightfully awarded to Degamo.28 Degamo thus took over as governor – though his time in office was cut short. The killing was carried out professionally by at least 16 ‘highly skilled’ and heavily armed assailants, including former dishonorably discharged soldiers and even a former New People’s Army rebel.29

The Degamo case is somewhat atypical in that the assailants and the mastermind were identified with relative speed. State prosecutors are considering Arnolfo Teves, Jr., the brother of Pryde Henry and a sitting member of Congress, the top mastermind in the killing.30 The Degamo killing thus demonstrates how some locally powerful elites continue to feel emboldened to engage in violent self-help. Such violence secures an elite’s continued political and economic interests – against not only those of a rival elite, but the public interest at large.

[Tomas Buenaventura is a Philippines Senior Research Assistant at ACLED.]

[The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) is a disaggregated data collection, analysis, and crisis mapping project. ACLED collects information on the dates, actors, locations, fatalities, and types of all reported political violence and protest events around the world. The ACLED team conducts analysis to describe, explore, and test conflict scenarios, and makes both data and analysis open for free use by the public.]

https://acleddata.com/2023/06/22/special-issue-on-the-targeting-of-local-officials-the-philippines/