From the Brookings Institute (Dec 16): Malaysia: Clear and present danger from the Islamic State

Two weeks ago, an internal Malaysian police memo was leaked to the media. The leak came after Malaysian Defense Minister Hishammuddin Hussein said he and several other Malaysian leaders were on the IS hit list. The memo gave details of a November 15th meeting between the militant groups Abu Sayyaf, the Islamic State (IS), and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), in Sulu, the southern Muslim-majority part of the Philippines. Attendees passed several resolutions at the meeting, including regarding mounting attacks in Malaysia, in particular Kuala Lumpur and Sabah in eastern Malaysia. The report mentioned that eight Abu Sayyaf and IS suicide bombers were already on the ground in Sabah, while another ten were in Kuala Lumpur.

While the news shocked many Malaysians and foreigners living in Malaysia, for Malaysia watchers, it was nothing new. There is general consensus in Malaysian security and intelligence circles that IS and home-grown Islamic radicals are planning a terrorist attack in Malaysia. For the past two years, in fact, Malaysia’s security services managed to disrupt at least four major bombing attempts. Their targets are mainly symbolic, such as beer factories and government buildings. Others were senior political figures and tycoons to be held for ransom and propaganda. IS regards the Malaysian government (and neighboring Indonesia) as un-Islamic and a pawn of the West.

While the Malaysian government is lucky that its intelligence services are on top of the situation, there are recent signs that they may be overwhelmed by the scale of the threat and the number of operatives involved.

Malaysia has a population of about 31 million, and 60 percent are Sunni Muslims. There are approximately 200-250 IS fighters from Malaysia in the Middle East. Contrast this with Indonesia, with a Muslim population of 300 million, and yet there are less than 400 IS fighters from Indonesia. This imbalance alone gives a clear indication of the scale of the problem Malaysia faces.

Even so, at the top of the Malaysian government, other than occasional statements condemning IS terrorism, officials do not seem to be able or willing to confront the root causes of the rise of IS in Malaysia.

In an influential essay published in April this year, Brookings scholar Joseph Liow laid out clearly the reasons for the rise of IS in Malaysia: the politicization of Islam by the state. In particular, both the ruling UMNO (United Malays National Organisation) party and its main opponent, PAS (Parti Islam Se-Malaysia) use political Islam as their weapon of choice.

The use of political Islam is a deliberate move by a group of committed Islamists hidden in the highest level of the Malaysian state and bureaucracy to create a Malay-Islamic state, not a mere theocratic state. This ideology is unique and separate from the caliphate project pursued by IS.

In the Malaysian version of the Malay-Islamic state, Sunni Islam’s supremacy is indivisible from ethnicity, i.e. the Malay race. In other words, the unique Malaysian brand of Sunni Islamic supremacy is fused with intolerant Malay nationalism. This highly committed group is trying to build the world’s only Islamic state where Islam and one particular ethnic group are one and the same.

Outsiders, including Muslims from other parts of the Sunni world, will find this development hard to understand as orthodox Islam rejects the notion of race or racism. In Malaysia, according to the proponents of ethno-religious nationalism, the Malaysian brand of Sunni Islam is unique. An example of these exclusion tactics is the issue over the usage of ‘Allah’. Despite clear and unequivocal evidence that the word ‘Allah’ can be used freely by all, the Malaysian religious establishment has claimed exclusive copyright over the word ‘Allah’ and codified into law a proscription that only Muslims can use ‘Allah’ and another half-a-dozen words.

Who are members of this group pushing for the Malay-Islamic state? The obvious candidates are JAKIM (Malaysian Islamic Development Department), a department under the prime minister’s office, and its state-level version. JAKIM is a government department tasked with defining, to the minuscule detail, what being a Sunni Muslim means in Malaysia, not only in theological terms but also in practical terms, like how to dress and what types of behavior are halal (permissible) or haram.

JAKIM, established during the era of Mahathir, prime minister from 1981 to 2003, is so powerful now that even senior UMNO leaders do not dare to confront it. Anyone who questions JAKIM is threatened with sedition. JAKIM threatened a former MP from UMNO with sedition. The son of a deputy prime minister, he had called for the departmental group to be disbanded. Police investigated a well-known lawyer for sedition after he tweeted, “Jakim is promoting extremism every Friday. Govt needs to address that if serious about extremism in Malaysia.” JAKIM writes all Friday sermons for delivery nationwide, and in recent years these sermons have tried to demonize Shiites, Christians and Jews.

JAKIM’s annual budget is about RM 1 billion, paid for by Muslim and non-Muslim taxpayers. Yet JAKIM is largely unaccountable to anyone. Progressive Malaysian Muslims fear the label of being branded anti-Islamic for questioning the work of JAKIM. Others shy away from criticizing JAKIM for fear of being charged with sedition.

Another government department promoting ethno-religious hate and intolerance is Biro Tata Negara (National Civics Bureau, or simply BTN). Like JAKIM, BTN is also under the authority of the PM’s office. Officially, BTN is supposed to nurture the spirit of patriotism. While many of its programs do promote patriotism among Malaysian youth, others promote racism toward non-Malays and filter their message to selected groups of Malay participants. The BTN teaches these Malay participants that the Malaysian Chinese (and non-Malays generally) are like “Jews” and that Malays must be politically supreme at all times. A recent exposé of internal BTN documents showed that BTN trainers were told to teach that racism is “good” if it promotes Malay unity. It even suggested that racism originated from the Islamic concept of asabiyyah, a positive idea that centered on brotherhood and formed social solidarity in historical Muslim civilizations.

While it is obvious that JAKIM, BTN, and similar bodies, do not officially support IS’s caliphate project or its murderous ideology, their promotion of a uniquely narrow Malay-Islamic worldview indirectly supports and complements the IS brand of intolerance. Many young Malays at the primary and high school level in the Malaysian school system are steeped in a view of Malay Islam that resonates with the IS worldview that there is an “us-versus-them” world order. Malaysian Muslims find IS’s ideology easy to accept, having grown up with a state-sanctioned view of intolerance towards non-Malay Muslims.

Is it any wonder that in a recent PEW poll, 11 percent of Malaysian Muslims had a “favorable” view of IS? What is even more interesting is that in Southeast Asia, Malaysian Muslims are more likely than Indonesian Muslims to consider suicide bombing justifiable (18 percent versus 7 percent).

If we make inferences from this context, there are two clear conclusions. First, there is going to be an IS attack in Malaysia – not if, but when. The number of IS supporters in Malaysia has reached a critical mass: a Malaysian minister revealed a few days ago there are approximately 50,000 IS supporters in Malaysia. Coupled with returning IS fighters from Syria and Iraq, this broad-based support means that one of their attacks will succeed.

Second, support for IS and intolerant Islam is growing in Malaysia due to the deliberate policies of government bodies such as JAKIM and BTN, whose worldview is increasingly becoming even more influential than that promulgated by elected political leaders. The situation can only get worse until the top UMNO leaders rein in JAKIM and similar bodies. If the government waits for a successful attack before undertaking any serious action, it will simply be too late.

http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2015/12/16-malaysia-danger-from-islamic-state-chin

Wednesday, December 16, 2015

MILF denies coddling alleged IS sympathizer

From the Manila Bulletin (Dec 16): MILF denies coddling alleged IS sympathizer

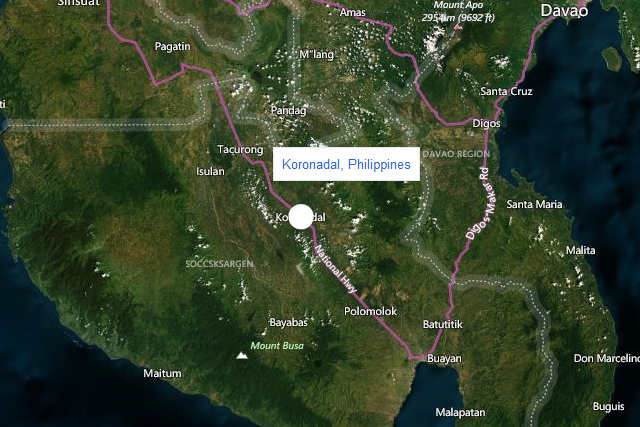

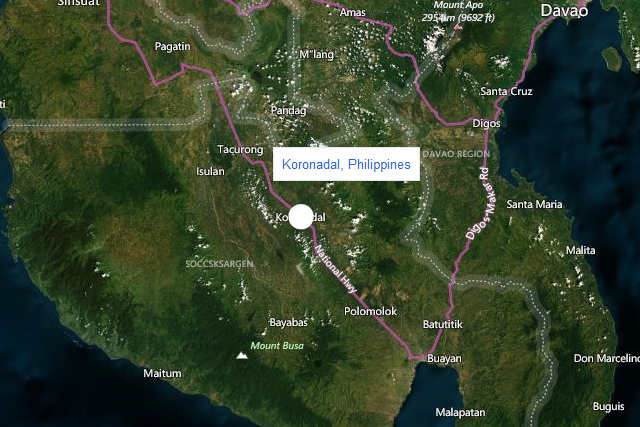

Davao City – The Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) has denied providing sanctuary for bandit group leader Mohamad Jaafar Sabiwang Maguid, alias Kumander Tokboy and his men, who are believed to be sympathizers of worldwide terror group Islamic State (IS) and whose camp was overrun by government forces in Barangay Butril in Palimbang, Sultan Kudarat last November 26.

This was the denial issued by the MILF side during discussions at the 44th regular meeting of the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Coordinating Committee on the Cessation of Hostilities (CCCH) that was concluded Tuesday at the Waterfront Insular Hotel here.

Combined military and police forces had tried to serve a warrant on Maguid last November 26 at his known lair in Palimbang but his men decided to shoot it out with authorities, a clash that lasted four hours in Sitio Sinapingan.

In a statement, the MILF said the allegations that it was coddling Maguid and his men were “baseless (since) it was also running after Kumander Tokboy,” which the group also considers as “lawless.”

In the meeting were GPH-CCCH chairman Brig. Gen. Glenn Macasero, his MILF counterpart Butch Malang, GPH peace panel member Senen Bacani and International Monitoring Team (IMT-10) head of mission Maj. Gen. Dato Shiekh Mokhsin Shiekh Hassan.

The MILF also manifested its “continuing efforts to resolve reported cases of ‘rido (family feud)’ in Bangsamoro areas through its Task Force on Conflict Resolution Management (TFCRM).”

The GPH-MILF regular meeting also resulted in the issuance of a joint statement on the CCCH’s “continued efforts to end conflicts and curb criminalities in Bangsamoro.”

An improved feedback system, which takes into consideration “coordination protocol” and “prior coordination before the movement of GPH and MILF forces near or within the MILF communities” was also tackled during the meeting.

The GPH and the MILF also agreed to fully cooperate through various ceasefire mechanisms in the protection of vital installations, civilian targets, AFP/PNP personnel and BIAF-MILF (Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces) members from the attacks of lawless elements.

http://www.mb.com.ph/milf-denies-coddling-alleged-is-sympathizer/

This was the denial issued by the MILF side during discussions at the 44th regular meeting of the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Coordinating Committee on the Cessation of Hostilities (CCCH) that was concluded Tuesday at the Waterfront Insular Hotel here.

Combined military and police forces had tried to serve a warrant on Maguid last November 26 at his known lair in Palimbang but his men decided to shoot it out with authorities, a clash that lasted four hours in Sitio Sinapingan.

When the smoke cleared, eight of Maguid’s men, including a suspected Indonesian bomb maker, lay dead as government troops took down the black flag of IS which flew over the compound and replaced it with the Philippine flag. The group’s leader was, however, able to escape.

In the meeting were GPH-CCCH chairman Brig. Gen. Glenn Macasero, his MILF counterpart Butch Malang, GPH peace panel member Senen Bacani and International Monitoring Team (IMT-10) head of mission Maj. Gen. Dato Shiekh Mokhsin Shiekh Hassan.

The MILF also manifested its “continuing efforts to resolve reported cases of ‘rido (family feud)’ in Bangsamoro areas through its Task Force on Conflict Resolution Management (TFCRM).”

The GPH-MILF regular meeting also resulted in the issuance of a joint statement on the CCCH’s “continued efforts to end conflicts and curb criminalities in Bangsamoro.”

An improved feedback system, which takes into consideration “coordination protocol” and “prior coordination before the movement of GPH and MILF forces near or within the MILF communities” was also tackled during the meeting.

The GPH and the MILF also agreed to fully cooperate through various ceasefire mechanisms in the protection of vital installations, civilian targets, AFP/PNP personnel and BIAF-MILF (Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces) members from the attacks of lawless elements.

http://www.mb.com.ph/milf-denies-coddling-alleged-is-sympathizer/

The Peace Process in Mindanao, the Philippines: Evolution and Lessons Learned

From the International Relations and Security Network (Dec 17): The Peace Process in Mindanao, the Philippines: Evolution and Lessons Learned by Kristian Herbolzheim for Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre (NOREF)

What lessons should we learn from the Philippine government’s multi-year peace efforts with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front? Kristian Herbolzheimer’s answers remind us that 1) peace is not so much a product as it is a process, and 2) negotiations are just one path to reconciliation.

Executive summary

The Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (2014) marks the first significant peace agreement worldwide in ten years and has become an inevitable reference for any other contemporary peace process. During 17 years of negotiations the government of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front managed to build up a creative hybrid architecture for verifying the ceasefire, supporting the negotiations and implementing the agreements, with the participation of Filipinos and members of the international community, the military and civilians, and institutions and civil society. This report analyses the keys that allowed the parties to reach an agreement and the challenges ahead in terms of implementation. It devotes special attention to the management of security-related issues during the transition from war to peace.

Introduction

On March 27th 2014 the government of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) signed an agreement to end an armed conflict that had started in 1969, caused more than 120,000 deaths and forcibly displaced hundreds of thousands of people. The Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro is the main peace agreement to be signed worldwide since the agreement that stopped the armed conflict in Nepal in 2006.

Every peace agreement addresses a particular context and conflict. However, the Mindanao process is now a crucial reference for other peace processes, given that it is the most recent. Of the 59 armed conflicts that have ended in the last 30 years, 44 concluded with peace agreements (Fisas, 2015: 16). The social, academic, and institutional capacities to analyse these processes and strengthen peacebuilding policies have thrived in parallel (Human Security Report Project, 2012). However, no peace process has been implemented without some difficulties. For this reason all peace processes learn from previous experiences, while innovating in their own practices and contributing overall to international experience of peacebuilding. The Mindanao peace process learned lessons from the experiences of South Sudan, Aceh (Indonesia) and Northern Ireland, among others.

Currently, other countries affected by internal conflicts such as Myanmar, Thailand and Turkey are analysing the Mindanao peace agreement with considerable interest. This report analyses the keys that allowed the parties to reach an agreement and the challenges facing the Philippines in terms of implementation. The report targets an international audience and aims to provide reflections that might be useful for other peace processes.

After introducing the context and development of the Mindanao peace process, the report analyses the actions and initiatives that allowed negotiations to make progress for 17 years and the innovations brought about by this process in areas such as public participation. Particular attention is devoted to the security-related agreements (including arms decommissioning by the insurgency) and to the mechanisms accompanying and verifying the agreement’s implementation.

Context

The Philippines is an archipelago comprising around 7,000 islands. Remarkable among them are the largest one, Luzon (where the capital, Manila, is situated) and the second largest, Mindanao. Together with Timor-Leste, this is the only Asian country with a majority Christian population. Around 100 million people live in a territory covering 300,000 km 2 . The system of government is presidential and executive power is limited to a single term of six years. The country owes its name to King Philip II of Spain, in whose service Magellan was sailing around the world when he arrived at the archipelago in 1521. After being a Spanish colony for three centuries, in 1898 the Philippines came under U.S. administration. A detail with far-reaching consequences is that Spain never took real control of the island of Mindanao. Islam had arrived three centuries before Magellan, and the Spanish found a well- consolidated system of governance, mainly through the sultanates of Maguindanao and Sulu. In 1946 the Philippines was the first Asian country to gain independence without an armed struggle (one year before India). It was also a pioneer in putting an end to a despotic regime by peaceful means when a non-violent people’s revolution overthrew the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in 1986. In 2001 a second people’s power revolution brought the government of Joseph Estrada – who was accused of corruption – to an end. Even so, the developments that have occurred over nearly 30 years of democracy have been slow. Politics continues to be the feud of a few families who perpetuate themselves in power from generation to generation. Relatives of deposed presidents remain active in politics and enjoy significant support. Some indicators show advances in poverty reduction, literacy and employment, but neighbouring countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand are far ahead in this regard (UNDP, 2015). The persistence of social inequalities feeds the discourse of the New People’s Army, a Maoist- inspired insurgency that has been active since 1968. Apart from the armed conflict in Mindanao and the communist insurgency, in recent years the Philippines has also suffered the onslaught of cells of Islamist terrorists linked to transnational networks.

Roots and humanitarian consequences of the conflict

The Muslim population of Mindanao has experienced harassment and discrimination since the times of the Spanish colony (1565-1898). The U.S. colonial administration (1898-1945) initiated a process of land entitlement that privileged Christian settlers coming from other islands of the archipelago. This policy of land dispossession continued after independence, coupled with government policies aimed at the assimilation of the Muslim minority.

Currently, the Muslim population is in the majority only in the western part of Mindanao and in the adjacent islands that proliferate up to the borders of Malaysia and Indonesia. Ten per cent of the population in this area are non-Islamised indigenous peoples. In 1968 an alleged massacre of Muslim army recruits in Manila led to the creation of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), which started an armed struggle for independence. In 1996 the government and the MNLF signed a peace agreement that granted autonomy to provinces with a Muslim majority. The group demobilised as a result, but a breakaway subgroup, the Islamic Front, rejected the terms of the agreement. However, this insurgency’s preference for a negotiated solution led to the signing of a bilateral ceasefire in 1997 and the start of formal peace negotiations in 1999.

The armed conflict in Mindanao has caused around 120,000 deaths, especially in the 1970s. In the 21st century it has been a low-intensity conflict, but continuous instability has generated a phenomenon of multiple displacements: thousands of people flee when there are skirmishes – which sometimes involve other armed actors – and return to their homes once the situation is stabilised. In 2008 the last political crisis in the peace process triggered the displacement of around 500,000 people in a few weeks in what became the most severe humanitarian crisis in the world at the time.

Structure and development of the negotiations

The negotiations lasted for 17 years (1997-2014) and were initially conducted in the Philippines and without mediation. Since 1999 the negotiating teams comprised five plenipotentiary members, with the support of a technical team of around ten people (a variable number). The intensity and duration of the negotiations oscillated over the years. In the last period (2009-14) the parties met in 26 negotiation rounds each lasting between three and five days.

The negotiations were halted on three occasions, triggering new armed confrontations in 2000, 2003 and 2008. After each one the parties agreed on new mechanisms designed to strengthen the negotiations infrastructure. In 2001 the Malaysian government accepted the request of the government of the Philippines to host and facilitate the negotiations. In 2004 the parties agreed to create an International Monitoring Team (IMT) to verify the ceasefire, comprising 50 unarmed members of the armed forces of Malaysia, Libya and Brunei cantoned in five cities in the conflict area. In 2009 this team was expanded and strengthened: two officers of the Norwegian army reinforced the security component, while the European Union (EU) provided two experts in human rights, international humanitarian law and humanitarian response.

In parallel, the IMT incorporated a Civilian Protection Component comprising one international and three local non-governmental organisations (NGOs). In 2009 the negotiating parties agreed to create an International Contact Group (ICG) to act as observers at the negotiations and advise the parties and the facilitator. 1 The ICG is formed by four countries (Britain, Japan, Turkey and Saudi Arabia), together with four international NGOs (Conciliation Resources, the Community of Sant Egidio, the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and Muhammadiyah).

Peace agreements

The negotiations started in 1997 with an agreement on a general cessation of hostilities. In the Tripoli Agreement (2001) the parties defined a negotiation agenda with three main elements: security (which had already been agreed on in 2001); humanitarian response, rehabilitation and development (agreed in 2002); and ancestral territories (2008). In October 2012 the parties finally adopted the Framework Agreement establishing a roadmap for the transition. In the following 15 months the parties concluded the annexes on transitional modalities (February 2013), revenue generation and wealth sharing (July 2013), power sharing (December 2013), and normalisation (January 2014). Finally, in March 2014 the Comprehensive Agreement was signed in the Presidential Palace.

The central axis of the agreement is the establishment of a new self-governing entity called Bangsamoro, which will replace the existing Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao after a transition led by the MILF. The agreement envisages a process of reform in the new autonomous region that will replace the presidential system that governs the rest of the country with a parliamentary one. The objective is to promote the emergence of programmatic political parties.

The government understands that the insurgency must be part of the solution and must assume the corresponding responsibilities. To this end it has encouraged the transformation of the insurgency into a political movement able to take part in local and regional elections. In terms of endorsement, the peace agreement must be transformed into a law that will regulate the Statute of Autonomy, called the Bangsamoro Basic Law.

After parliamentary approval, a plebiscite will be held in the conflict-affected areas. This plebiscite will also serve to determine the territorial extent of the autonomous region, since the municipalities bordering the current autonomous community will have the option to join the new entity. Constitutional reform is a contentious issue. The MILF insists on the need for reform in order to consolidate the agreements.

However, the government has been reluctant to initiate a process that could be tedious and could open a “Pandora’s box”. But doubts about some of the agree - ments’ compliance with the constitution suggest that such a reform process might eventually be discussed. Beyond the agreement with the MILF, the peace process in Mindanao could contribute to opening a national debate about the territorial organisation of the country, since important sectors in other regions are demanding broad constitutional reform along federal lines.

Roadmap of the transition

A controversial issue during the negotiations was the expected time line for implementation. The MILF suggested a six-year period, while the government refused to make commitments beyond its presidential term (2010-16), since the Philippine political system lacks guarantees in terms of the continuity of public policies from one administration to the next. Finally, the MILF accepted this argument and the 2012 Framework Agreement defined a roadmap for implementation with a time horizon of the presidential elections of May 2016.

The key implementation institutions are as follows:

1. The Transition Commission comprises 15 people (seven appointed by each side, under an MILF chairperson). Its main mission was the drafting of the Bangsamoro Basic Law, which was submitted to Congress for approval in September 2014.

2. The Transitional Authority will be headed by the MILF and will comprise representatives of various social, political and economic actors from the autonomous region. It will be formally set up after the Basic Law is enacted by Congress. Its mission will be to pilot the transformation of the existing autonomous institutions until the holding of elections for a new autonomous government (initially expected in May 2016, although they might need to be postponed).

3. The Third Party Monitoring Team (TPMT) is in charge of monitoring the implementation of the agreements. It comprises five members (two representatives of national NGOs, two of international NGOs, and a former EU ambassador to the Philippines who acts as coordinator). The TPMT issues periodic reports for both parties, and public reports twice a year. But its most relevant role – and probably the most controversial – will be to certify the end of the implementation process, which, in turn, conditions the MILF decommissioning process.

4. Despite the fact that both parties are represented in all the relevant organs, the negotiating teams remain an organ of last resort to resolve potential problems or disagreements. Malaysia – the facilitator country – and the ICG continue to provide support at the request of the parties.

The challenge of normalisation

Apart from enacting the Bangsamoro Basic law and adapting the various regional institutions to the new Statute of Autonomy, the main objective of the transitional period is the consolidation of normalisation , which is under - stood as “a process whereby communities can achieve their desired quality of life, which includes the pursuit of sustainable livelihood and political participation within a peaceful deliberative society”. 2 The concept of normalisation includes what is termed disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration in other contexts, as well as additional elements aimed at the consolidation of peace and human security. The process of normalisation has four essential elements:

1. The first is socioeconomic development programmes for conflict-affected areas. The MILF-led Bangsamoro Development Agency will be in charge of coordination, together with the Sajahatra presidential programme of immediate relief to improve health conditions, educa - tion and development.

2. Confidence-building measures include two key processes. Firstly, development programmes will be aimed specifically at MILF members and their relatives in their six main camps. Secondly, the government will commit to using amnesties, pardons, and other avail - able mechanisms to resolve the cases of people accused or convicted of actions and crimes related to the Mindanao armed conflict. 3 It is worth noting that neither the MILF nor the government security forces face pending accusations of gross human rights violations or crimes against humanity.

3. In matters of transitional justice and reconciliation, a three-person team is mandated to elaborate a methodological proposal about how to address the legitimate grievances of the Bangsamoro (Muslim) people, correct historical injustices, and address human rights violations, including marginalisation due to land dispossession. The team can also propose programmes and measures to promote reconciliation between conflict-affected communities and heal the physical, mental and spiritual wounds caused by the conflict. This mandate includes the proposal of measures to guarantee non-repetition.

4. The sensitive issue of security has four elements. The first is reform of the police, since responsibility for public order will be given to a new police force for the Bangsamoro that will be civilian in character and accountable to the communities it serves. The negotiating parties commissioned the Independent Commission on Policing to draft a report with recommendations in this regard. This report was delivered in April 2015.

Secondly, the parties agreed to carry out a joint programme to identify and dismantle “private” armed groups (paramilitaries), which are often controlled by mayors and governors. The operational criteria for this task are still awaiting development. The third element is arms decommissioning by the MILF. This process is defined as the activities aimed at facilitating the transition of the insurgent forces to a productive civilian life. An Independent Decommissioning Body (IDB) is in charge of registering the MILF’s members and weapons, and planning the phases of collecting, transporting and storing weapons. 4 There is as yet no agreement among the parties on the final destination of the weapons decommissioned by the insurgency, and they will be temporarily stockpiled in containers and subject to joint supervision by the insurgency and security forces under international coordination. The MILF has committed to total decommissioning to be undertaken in phases conditioned on the implementation of the agreements, as described in the following table:

(insert)

The Agreement on Normalisation established a time frame of two years to complete the process. The fourth and last security-related element affects the armed forces, who have committed to carrying out a repositioning to help facilitate peace and coexistence. This repositioning will be based on a joint evaluation of the security conditions.

Other normalisation-related elements

A Joint Normalisation Committee will coordinate the overall normalisation process. In terms of financing, the government will assume the responsibility to supply the funds necessary to sustain the process, while the MILF has the right to procure and manage additional funds. A Joint Peace and Security Committee has overall responsibility for the supervision of all security-related matters of normalisation until the full deployment of the new Bangsamoro Police.

On the operative side, Joint Peace and Security Teams (comprising members of the armed forces, police and the MILF) will handle law and order in the areas agreed by the parties. In parallel, the existing mechanisms for ceasefire verification will remain operative (the Coordi - nation Committee for the Cessation of Hostilities, the Ad Hoc Joint Action Group (AHJAG) to combat crime in MILF areas and the IMT).

The Agreement on Normalisation does not refer to the MILF cantonments because this point was discussed in the framework of the 1997 bilateral ceasefire agreement. After intense debates the parties identified major and satellite camps where the combatants and their relatives had a stable presence and formed rural communities. There was no registry of members of these communities or their weapons, and free individual movement is allowed. The agreement also established that any movement of troops – by the insurgency or security forces – should be coordinated with the other party. A special agreement (the AHJAG) allows the police to maintain public order in MILF-controlled areas in prior coordination with the MILF.

The state performs its administrative duties under normal conditions in the whole territory. A difference from the Final Agreement reached with the MNLF in 1996 is that this agreement does not provide for the integration of MILF combatants into the security forces, except for the new autonomous police. In terms of de-mining, in 2002 the MILF adhered to the Geneva Call against the use of anti-personnel mines.

In 2010 the government and MILF agreed to allow the Philippines Campaign against Land Mines to conduct civic education and the identification and destruction of unexploded ordnance. Enabling factors for the peace process First and foremost, both parties have long acknowledged the limits of armed confrontation. In 2000 the government broke off the ceasefire to launch “all-out-war”, which led to the MILF’s military defeat in just four months. However, both the government and the security forces realised that the root causes of the problem were not resolved and that the Muslim population retained an unbroken determination to fight for its identity and dignity. From the perspective of the insurgency, since its creation the MILF recognised that armed victory was not possible, and instead focused on the primacy of peace negotiations.

More recently, the reformist government of Benigno Aquino promoted a change in the country’s military doctrine (AFP, 2010) in the framework of its commitment to resolve internal armed conflicts and deal with the growing geopolitical challenges resulting from China’s emergence as a regional power. The new objective is no longer to “win the war”, but to “win the peace”, and the new doctrine emphasises the establishment of relations of trust with the communities affected by the conflict. The overall goal is the liberation of human and financial resources previously devoted to the internal confrontation in order to be able to better deal with external threats. Interestingly, the parties have also understood the limits of peace negotiations. Both the government and the insurgency admit that the reforms needed to acknowledge and respect the way of life and history of the Muslim and indigenous peoples demand a wide national consensus.

The problems that hampered the implementation of past peace agreements highlight the need for a collective ownership of the peace process and its results by society. For this reason both parties have engaged in intensive consultations with the social, academic, political and institutional sectors with the double objective of strengthening the process with the inputs of those who support it, and listening and responding to the concerns of those who are more sceptical and potentially opposed to the negotiations. On several occasions the MILF has gathered hundreds of thousands of followers in huge conventions to ratify the decisions of its Central Committee.

Apart from these consultation processes, the government and the insurgency have included civil society members in their teams and on several occasions have invited civil society delegates and members of Congress to witness the negotiations. The parties also agreed on the participation of civil society in several of the bodies involved in the implementation of the agreements, notably the TPMT. These institutional efforts towards inclusion are largely a response to the pressures of an organised civil society that has relentlessly promoted peacebuilding initiatives parallel to the negotiations. These initiatives include the creation of peace zones, inter-religious dialogues, capacity-building in the theory and practice of conflict resolution, the consolidation of citizen agendas, lobbying the armed actors, and the creation of ceasefire monitoring mechanisms such as the Bantay Ceasefire or the Civil Protection Component of the IMT. Some additional elements help explain the progress of the negotiations:

• The parties’ pragmatism and realism: The insurgency abandoned the objective of total independence in the context of negotiations, while the country’s various governments have all recognised the existence of the root causes of the conflict and committed to a solution based on dialogue.

• Confidence-building measures: The lengthy bilateral ceasefire contributed to building trust between the insurgency and military and police commanders, including at the personal level. This trust is currently the main guarantor that there will be no relapse into armed confrontation. Furthermore, both parties recognise nternational humanitarian law and international human rights treaties (on the recruitment of child soldiers, the prohibition of the use of anti-personnel mines, etc.)These factors have been fundamental in reducing the levels of confrontation and generating trust between the parties and civil society.

• Strengthening of capacities: Both the government and the MILF are well aware of the problems that emerged during the implementation of the 1996 agreement with

the MNLF. The parties therefore decided early on to strengthen the capacity of the MILF to manage civil institutions: in 2002 they created the Bangsamoro Development Agency and in 2009 the Bangsamoro Leadership and Management Institute, both led by the MILF.

Additional highlights

The main peacebuilding developments in the Philippines emerged during the presidency of Fidel Ramos (1992-98). Ramos was a retired general who had been chief of staff of the armed forces during the Marcos dictatorship as well as during the first democratic government, i.e. of President Corazón Aquino. In 1992 Ramos promoted an ambitious process of national dialogue (Coronel-Ferrer, 2002) for the drawing up of a national peace policy. The result of this consultation was a conceptual framework that identified the structural problems affecting the country and defined “six paths to peace”.

The conceptual framework emphasises negotiations between the government and the insurgency as one of the paths to peace, but states that a peace process must necessarily be wider and more inclusive than mere peace negotiations. This innovative national peace policy has coexisted for years in contrast to (and in conflict with) a classic national security doctrine focused on defeating the internal enemy. In 2003 a crisis in negotiations and the return of violent incidents mobilised civil society to promote an initiative of its own to verify the ceasefire, known as the Bantay Ceasefire.

The network was composed of around 200 voluntary members and, despite the financial constraints it faced, became an essential complement to the formal verification commissions, receiving the appreciation of both parties. An additional element is the outstanding role played by women in the peace process. The Philippines is possibly the country with the best implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) on women, peace and security. Teresita Deles holds the position of presidential adviser for peace, while Miriam Coronel was the first woman to lead a negotiating team that eventually signed a peace agreement. Women have also led the legal advisory teams of both the government and the MILF. Similar to other contexts, women in the Philippines have a wide presence and leadership role in civil society, with Muslim and indigenous women playing a fundamental role (Herbolzheimer, 2013; Conciliation Resources, 2015).

Implementation challenges

In spite of the positive developments, the implementation of the peace agreement is facing multiple obstacles. The first limiting factor is time. During the negotiation of the Framework Agreement (2012) the government man - aged to link the transitional period to the end of the presidential term in May 2016. But the negotiating teams have not been able to keep up the agreed pace of negotiation and implementation. As a result, the parties will have to agree to an extension of the implementation period. Responsibility for the delay is shared. On the one hand, the insurgency lacks enough qualified and reliable/trustworthy personnel to take on all the responsibilities derived from the transition.

On the other hand, the government negotiating team has to deal with limited buy-in on both the agreement and its implementation by other sectors of the bureaucracy. At the same time Congress has been dragging its feet in enacting the peace agreements into law, while the judiciary must still assess whether the agreements comply with the constitution. There is a high risk that these two state institutions will raise issues that may further block the implementation of the agreements that have been signed.

Furthermore, in the Philippines, prejudice against Muslims – a heritage from the colonial period – still runs deep. With less than a year remaining until the country’s presidential and legislative elections (May 2016), some prominent politicians and media outlets are turning to populist rhetoric to antagonise public opinion against the peace process. Even among better-intentioned political actors, a lack of knowledge about the social, political, and cultural reality of the insurgency in particular and the Muslim population in general results in faulty diagnoses and mistaken responses.

Successive governments have associated the Moro problem with poverty and economic marginalisation, thus neglecting the relevance of identity and parity of esteem. On its part, the insurgency has been unable to articulate a political discourse that the whole country can understand and endorse. Only after patient dialogue have the peace negotiators deconstructed some of these erroneous imaginaries, but both the Christian and Muslim sectors of society still distrust each other.

The main security-related problem is the proliferation of arms and armed groups. One reason is that holding weapons is legal in the Philippines. Related to this, successive governments have failed in their attempts to disband paramilitary groups run by local politicians. There is also a proliferation of additional armed groups, which can be classified into three categories: an MILF breakaway group that is sceptical about the government’s political commitment (the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters); extremist cells linked to international extremist violence (Abu Sayyaf, Jemaa Islamiyah); and ordinary criminal organisations. Other difficulties are inherent to any process of transition from war to peace. Apart from political will, the government needs to prove its capacity to transform words into deeds, which has historically proved to be a challenge. In parallel, the insurgency needs a radical paradigm shift from a semi-clandestine military structure to a social and political movement – a terrain in which it has limited experience and where to some extent it is at a disadvan - tage compared to more established political actors.

Lessons learned for other peace processes

Each peace process responds to a specific conflict that emerges for concrete reasons and in concrete circumstances (social, political, cultural and temporal). However, comparative analysis is fundamental in every peace process. Some of the lessons from the Philippines could be relevant to other contexts:

• Peace is not a product, but a process. The transformative capacity of a peace agreement and its sustainability over time depend on its legitimacy, which in turn is dependent on the extent that social, political and economic actors feel a sense of ownership of the deliberative process leading to the peace agreements and their implementation.

• Negotiations are just one among multiple paths to peace. In parallel to the negotiations between the government and the insurgency, other dialogue processes must build or restore relations between sectors of society that have been or remained divided during the armed conflict. This is essential to achieving the social, political, economic and cultural transformations needed to overcome a protracted armed conflict.

• The current context demands efforts to facilitate the participation of historically excluded sectors such as women, victims and ethnic communities. Including these sectors greatly contributes to raising the international legitimacy of a peace process.

• The crises that emerge during negotiations are also opportunities to improve the mechanisms that support the talks.

• A government involved in a peace process must include the legislature and take into account the perceptions of the judiciary before the signing of an agreement. Constitutional amendments are the best guarantee to consolidate a country’s structural transformation.

• Giving an insurgency the opportunity to transform itself into a political movement free of coercion and threats is the best guarantee of the non-recurrence of armed conflict. Such an evolution can be enhanced by preventing the potential social and political isolation of the insurgency, as well as agreeing on transitional measures for the political participation of the insurgency before it can compete on equal terms with more established political movements.

• The decommissioning of arms by the insurgency, and the repositioning and reform of the government security sector are gradual and interdependent processes that contribute to confidence-building. The insurgency is aware that the hard-earned legitimacy it has gained as a peace actor can be lost with just one mistake in the management of its weapons, or if it does not allow the state to be fully present and perform its social, administrative and public order duties in the whole territory.

• The implementation of a peace agreement can be as difficult as the negotiations. In the Philippines, this has been managed through the creation of hybrid agreement implementation bodies that allow the joint and complementary work of national and international, civil and military, institutional and civil society actors.

• The implementation of a peace agreement implies an asymmetric power relationship that is favourable to the state. If an insurgent movement does not comply with the agreement, it loses legitimacy. If the state does not comply, the insurgency has limited means to apply pressure because a return to armed conflict is not an option.

• The international community plays a decisive role in accompanying and supporting the peace process. But its role is always secondary and does not replace national leadership. The agenda for negotiations, the time line, the design of consultations, the terms of reference for international support, and other fundamental elements of a peace process are exclusively in the hands of national actors.

[Kristian Herbolzheimer has more than 15 years of experience in peacebuilding affairs, first as the director of the Colombia Programme at the School for a Culture of Peace in Barcelona, and since 2009 as director of the Colombia and Philippines programmes at Conciliation Resources.]

]This article was originally published by NOREF on 2 December 2015.]

http://www.isn.ethz.ch/Digital-Library/Articles/Detail/?lng=en&id=195251

What lessons should we learn from the Philippine government’s multi-year peace efforts with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front? Kristian Herbolzheimer’s answers remind us that 1) peace is not so much a product as it is a process, and 2) negotiations are just one path to reconciliation.

Executive summary

The Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (2014) marks the first significant peace agreement worldwide in ten years and has become an inevitable reference for any other contemporary peace process. During 17 years of negotiations the government of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front managed to build up a creative hybrid architecture for verifying the ceasefire, supporting the negotiations and implementing the agreements, with the participation of Filipinos and members of the international community, the military and civilians, and institutions and civil society. This report analyses the keys that allowed the parties to reach an agreement and the challenges ahead in terms of implementation. It devotes special attention to the management of security-related issues during the transition from war to peace.

Introduction

On March 27th 2014 the government of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) signed an agreement to end an armed conflict that had started in 1969, caused more than 120,000 deaths and forcibly displaced hundreds of thousands of people. The Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro is the main peace agreement to be signed worldwide since the agreement that stopped the armed conflict in Nepal in 2006.

Every peace agreement addresses a particular context and conflict. However, the Mindanao process is now a crucial reference for other peace processes, given that it is the most recent. Of the 59 armed conflicts that have ended in the last 30 years, 44 concluded with peace agreements (Fisas, 2015: 16). The social, academic, and institutional capacities to analyse these processes and strengthen peacebuilding policies have thrived in parallel (Human Security Report Project, 2012). However, no peace process has been implemented without some difficulties. For this reason all peace processes learn from previous experiences, while innovating in their own practices and contributing overall to international experience of peacebuilding. The Mindanao peace process learned lessons from the experiences of South Sudan, Aceh (Indonesia) and Northern Ireland, among others.

Currently, other countries affected by internal conflicts such as Myanmar, Thailand and Turkey are analysing the Mindanao peace agreement with considerable interest. This report analyses the keys that allowed the parties to reach an agreement and the challenges facing the Philippines in terms of implementation. The report targets an international audience and aims to provide reflections that might be useful for other peace processes.

After introducing the context and development of the Mindanao peace process, the report analyses the actions and initiatives that allowed negotiations to make progress for 17 years and the innovations brought about by this process in areas such as public participation. Particular attention is devoted to the security-related agreements (including arms decommissioning by the insurgency) and to the mechanisms accompanying and verifying the agreement’s implementation.

Context

The Philippines is an archipelago comprising around 7,000 islands. Remarkable among them are the largest one, Luzon (where the capital, Manila, is situated) and the second largest, Mindanao. Together with Timor-Leste, this is the only Asian country with a majority Christian population. Around 100 million people live in a territory covering 300,000 km 2 . The system of government is presidential and executive power is limited to a single term of six years. The country owes its name to King Philip II of Spain, in whose service Magellan was sailing around the world when he arrived at the archipelago in 1521. After being a Spanish colony for three centuries, in 1898 the Philippines came under U.S. administration. A detail with far-reaching consequences is that Spain never took real control of the island of Mindanao. Islam had arrived three centuries before Magellan, and the Spanish found a well- consolidated system of governance, mainly through the sultanates of Maguindanao and Sulu. In 1946 the Philippines was the first Asian country to gain independence without an armed struggle (one year before India). It was also a pioneer in putting an end to a despotic regime by peaceful means when a non-violent people’s revolution overthrew the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in 1986. In 2001 a second people’s power revolution brought the government of Joseph Estrada – who was accused of corruption – to an end. Even so, the developments that have occurred over nearly 30 years of democracy have been slow. Politics continues to be the feud of a few families who perpetuate themselves in power from generation to generation. Relatives of deposed presidents remain active in politics and enjoy significant support. Some indicators show advances in poverty reduction, literacy and employment, but neighbouring countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand are far ahead in this regard (UNDP, 2015). The persistence of social inequalities feeds the discourse of the New People’s Army, a Maoist- inspired insurgency that has been active since 1968. Apart from the armed conflict in Mindanao and the communist insurgency, in recent years the Philippines has also suffered the onslaught of cells of Islamist terrorists linked to transnational networks.

Roots and humanitarian consequences of the conflict

The Muslim population of Mindanao has experienced harassment and discrimination since the times of the Spanish colony (1565-1898). The U.S. colonial administration (1898-1945) initiated a process of land entitlement that privileged Christian settlers coming from other islands of the archipelago. This policy of land dispossession continued after independence, coupled with government policies aimed at the assimilation of the Muslim minority.

Currently, the Muslim population is in the majority only in the western part of Mindanao and in the adjacent islands that proliferate up to the borders of Malaysia and Indonesia. Ten per cent of the population in this area are non-Islamised indigenous peoples. In 1968 an alleged massacre of Muslim army recruits in Manila led to the creation of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), which started an armed struggle for independence. In 1996 the government and the MNLF signed a peace agreement that granted autonomy to provinces with a Muslim majority. The group demobilised as a result, but a breakaway subgroup, the Islamic Front, rejected the terms of the agreement. However, this insurgency’s preference for a negotiated solution led to the signing of a bilateral ceasefire in 1997 and the start of formal peace negotiations in 1999.

The armed conflict in Mindanao has caused around 120,000 deaths, especially in the 1970s. In the 21st century it has been a low-intensity conflict, but continuous instability has generated a phenomenon of multiple displacements: thousands of people flee when there are skirmishes – which sometimes involve other armed actors – and return to their homes once the situation is stabilised. In 2008 the last political crisis in the peace process triggered the displacement of around 500,000 people in a few weeks in what became the most severe humanitarian crisis in the world at the time.

Structure and development of the negotiations

The negotiations lasted for 17 years (1997-2014) and were initially conducted in the Philippines and without mediation. Since 1999 the negotiating teams comprised five plenipotentiary members, with the support of a technical team of around ten people (a variable number). The intensity and duration of the negotiations oscillated over the years. In the last period (2009-14) the parties met in 26 negotiation rounds each lasting between three and five days.

The negotiations were halted on three occasions, triggering new armed confrontations in 2000, 2003 and 2008. After each one the parties agreed on new mechanisms designed to strengthen the negotiations infrastructure. In 2001 the Malaysian government accepted the request of the government of the Philippines to host and facilitate the negotiations. In 2004 the parties agreed to create an International Monitoring Team (IMT) to verify the ceasefire, comprising 50 unarmed members of the armed forces of Malaysia, Libya and Brunei cantoned in five cities in the conflict area. In 2009 this team was expanded and strengthened: two officers of the Norwegian army reinforced the security component, while the European Union (EU) provided two experts in human rights, international humanitarian law and humanitarian response.

In parallel, the IMT incorporated a Civilian Protection Component comprising one international and three local non-governmental organisations (NGOs). In 2009 the negotiating parties agreed to create an International Contact Group (ICG) to act as observers at the negotiations and advise the parties and the facilitator. 1 The ICG is formed by four countries (Britain, Japan, Turkey and Saudi Arabia), together with four international NGOs (Conciliation Resources, the Community of Sant Egidio, the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and Muhammadiyah).

Peace agreements

The negotiations started in 1997 with an agreement on a general cessation of hostilities. In the Tripoli Agreement (2001) the parties defined a negotiation agenda with three main elements: security (which had already been agreed on in 2001); humanitarian response, rehabilitation and development (agreed in 2002); and ancestral territories (2008). In October 2012 the parties finally adopted the Framework Agreement establishing a roadmap for the transition. In the following 15 months the parties concluded the annexes on transitional modalities (February 2013), revenue generation and wealth sharing (July 2013), power sharing (December 2013), and normalisation (January 2014). Finally, in March 2014 the Comprehensive Agreement was signed in the Presidential Palace.

The central axis of the agreement is the establishment of a new self-governing entity called Bangsamoro, which will replace the existing Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao after a transition led by the MILF. The agreement envisages a process of reform in the new autonomous region that will replace the presidential system that governs the rest of the country with a parliamentary one. The objective is to promote the emergence of programmatic political parties.

The government understands that the insurgency must be part of the solution and must assume the corresponding responsibilities. To this end it has encouraged the transformation of the insurgency into a political movement able to take part in local and regional elections. In terms of endorsement, the peace agreement must be transformed into a law that will regulate the Statute of Autonomy, called the Bangsamoro Basic Law.

After parliamentary approval, a plebiscite will be held in the conflict-affected areas. This plebiscite will also serve to determine the territorial extent of the autonomous region, since the municipalities bordering the current autonomous community will have the option to join the new entity. Constitutional reform is a contentious issue. The MILF insists on the need for reform in order to consolidate the agreements.

However, the government has been reluctant to initiate a process that could be tedious and could open a “Pandora’s box”. But doubts about some of the agree - ments’ compliance with the constitution suggest that such a reform process might eventually be discussed. Beyond the agreement with the MILF, the peace process in Mindanao could contribute to opening a national debate about the territorial organisation of the country, since important sectors in other regions are demanding broad constitutional reform along federal lines.

Roadmap of the transition

A controversial issue during the negotiations was the expected time line for implementation. The MILF suggested a six-year period, while the government refused to make commitments beyond its presidential term (2010-16), since the Philippine political system lacks guarantees in terms of the continuity of public policies from one administration to the next. Finally, the MILF accepted this argument and the 2012 Framework Agreement defined a roadmap for implementation with a time horizon of the presidential elections of May 2016.

The key implementation institutions are as follows:

1. The Transition Commission comprises 15 people (seven appointed by each side, under an MILF chairperson). Its main mission was the drafting of the Bangsamoro Basic Law, which was submitted to Congress for approval in September 2014.

2. The Transitional Authority will be headed by the MILF and will comprise representatives of various social, political and economic actors from the autonomous region. It will be formally set up after the Basic Law is enacted by Congress. Its mission will be to pilot the transformation of the existing autonomous institutions until the holding of elections for a new autonomous government (initially expected in May 2016, although they might need to be postponed).

3. The Third Party Monitoring Team (TPMT) is in charge of monitoring the implementation of the agreements. It comprises five members (two representatives of national NGOs, two of international NGOs, and a former EU ambassador to the Philippines who acts as coordinator). The TPMT issues periodic reports for both parties, and public reports twice a year. But its most relevant role – and probably the most controversial – will be to certify the end of the implementation process, which, in turn, conditions the MILF decommissioning process.

4. Despite the fact that both parties are represented in all the relevant organs, the negotiating teams remain an organ of last resort to resolve potential problems or disagreements. Malaysia – the facilitator country – and the ICG continue to provide support at the request of the parties.

The challenge of normalisation

Apart from enacting the Bangsamoro Basic law and adapting the various regional institutions to the new Statute of Autonomy, the main objective of the transitional period is the consolidation of normalisation , which is under - stood as “a process whereby communities can achieve their desired quality of life, which includes the pursuit of sustainable livelihood and political participation within a peaceful deliberative society”. 2 The concept of normalisation includes what is termed disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration in other contexts, as well as additional elements aimed at the consolidation of peace and human security. The process of normalisation has four essential elements:

1. The first is socioeconomic development programmes for conflict-affected areas. The MILF-led Bangsamoro Development Agency will be in charge of coordination, together with the Sajahatra presidential programme of immediate relief to improve health conditions, educa - tion and development.

2. Confidence-building measures include two key processes. Firstly, development programmes will be aimed specifically at MILF members and their relatives in their six main camps. Secondly, the government will commit to using amnesties, pardons, and other avail - able mechanisms to resolve the cases of people accused or convicted of actions and crimes related to the Mindanao armed conflict. 3 It is worth noting that neither the MILF nor the government security forces face pending accusations of gross human rights violations or crimes against humanity.

3. In matters of transitional justice and reconciliation, a three-person team is mandated to elaborate a methodological proposal about how to address the legitimate grievances of the Bangsamoro (Muslim) people, correct historical injustices, and address human rights violations, including marginalisation due to land dispossession. The team can also propose programmes and measures to promote reconciliation between conflict-affected communities and heal the physical, mental and spiritual wounds caused by the conflict. This mandate includes the proposal of measures to guarantee non-repetition.

4. The sensitive issue of security has four elements. The first is reform of the police, since responsibility for public order will be given to a new police force for the Bangsamoro that will be civilian in character and accountable to the communities it serves. The negotiating parties commissioned the Independent Commission on Policing to draft a report with recommendations in this regard. This report was delivered in April 2015.

Secondly, the parties agreed to carry out a joint programme to identify and dismantle “private” armed groups (paramilitaries), which are often controlled by mayors and governors. The operational criteria for this task are still awaiting development. The third element is arms decommissioning by the MILF. This process is defined as the activities aimed at facilitating the transition of the insurgent forces to a productive civilian life. An Independent Decommissioning Body (IDB) is in charge of registering the MILF’s members and weapons, and planning the phases of collecting, transporting and storing weapons. 4 There is as yet no agreement among the parties on the final destination of the weapons decommissioned by the insurgency, and they will be temporarily stockpiled in containers and subject to joint supervision by the insurgency and security forces under international coordination. The MILF has committed to total decommissioning to be undertaken in phases conditioned on the implementation of the agreements, as described in the following table:

(insert)

The Agreement on Normalisation established a time frame of two years to complete the process. The fourth and last security-related element affects the armed forces, who have committed to carrying out a repositioning to help facilitate peace and coexistence. This repositioning will be based on a joint evaluation of the security conditions.

Other normalisation-related elements

A Joint Normalisation Committee will coordinate the overall normalisation process. In terms of financing, the government will assume the responsibility to supply the funds necessary to sustain the process, while the MILF has the right to procure and manage additional funds. A Joint Peace and Security Committee has overall responsibility for the supervision of all security-related matters of normalisation until the full deployment of the new Bangsamoro Police.

On the operative side, Joint Peace and Security Teams (comprising members of the armed forces, police and the MILF) will handle law and order in the areas agreed by the parties. In parallel, the existing mechanisms for ceasefire verification will remain operative (the Coordi - nation Committee for the Cessation of Hostilities, the Ad Hoc Joint Action Group (AHJAG) to combat crime in MILF areas and the IMT).

The Agreement on Normalisation does not refer to the MILF cantonments because this point was discussed in the framework of the 1997 bilateral ceasefire agreement. After intense debates the parties identified major and satellite camps where the combatants and their relatives had a stable presence and formed rural communities. There was no registry of members of these communities or their weapons, and free individual movement is allowed. The agreement also established that any movement of troops – by the insurgency or security forces – should be coordinated with the other party. A special agreement (the AHJAG) allows the police to maintain public order in MILF-controlled areas in prior coordination with the MILF.

The state performs its administrative duties under normal conditions in the whole territory. A difference from the Final Agreement reached with the MNLF in 1996 is that this agreement does not provide for the integration of MILF combatants into the security forces, except for the new autonomous police. In terms of de-mining, in 2002 the MILF adhered to the Geneva Call against the use of anti-personnel mines.

In 2010 the government and MILF agreed to allow the Philippines Campaign against Land Mines to conduct civic education and the identification and destruction of unexploded ordnance. Enabling factors for the peace process First and foremost, both parties have long acknowledged the limits of armed confrontation. In 2000 the government broke off the ceasefire to launch “all-out-war”, which led to the MILF’s military defeat in just four months. However, both the government and the security forces realised that the root causes of the problem were not resolved and that the Muslim population retained an unbroken determination to fight for its identity and dignity. From the perspective of the insurgency, since its creation the MILF recognised that armed victory was not possible, and instead focused on the primacy of peace negotiations.

More recently, the reformist government of Benigno Aquino promoted a change in the country’s military doctrine (AFP, 2010) in the framework of its commitment to resolve internal armed conflicts and deal with the growing geopolitical challenges resulting from China’s emergence as a regional power. The new objective is no longer to “win the war”, but to “win the peace”, and the new doctrine emphasises the establishment of relations of trust with the communities affected by the conflict. The overall goal is the liberation of human and financial resources previously devoted to the internal confrontation in order to be able to better deal with external threats. Interestingly, the parties have also understood the limits of peace negotiations. Both the government and the insurgency admit that the reforms needed to acknowledge and respect the way of life and history of the Muslim and indigenous peoples demand a wide national consensus.

The problems that hampered the implementation of past peace agreements highlight the need for a collective ownership of the peace process and its results by society. For this reason both parties have engaged in intensive consultations with the social, academic, political and institutional sectors with the double objective of strengthening the process with the inputs of those who support it, and listening and responding to the concerns of those who are more sceptical and potentially opposed to the negotiations. On several occasions the MILF has gathered hundreds of thousands of followers in huge conventions to ratify the decisions of its Central Committee.

Apart from these consultation processes, the government and the insurgency have included civil society members in their teams and on several occasions have invited civil society delegates and members of Congress to witness the negotiations. The parties also agreed on the participation of civil society in several of the bodies involved in the implementation of the agreements, notably the TPMT. These institutional efforts towards inclusion are largely a response to the pressures of an organised civil society that has relentlessly promoted peacebuilding initiatives parallel to the negotiations. These initiatives include the creation of peace zones, inter-religious dialogues, capacity-building in the theory and practice of conflict resolution, the consolidation of citizen agendas, lobbying the armed actors, and the creation of ceasefire monitoring mechanisms such as the Bantay Ceasefire or the Civil Protection Component of the IMT. Some additional elements help explain the progress of the negotiations:

• The parties’ pragmatism and realism: The insurgency abandoned the objective of total independence in the context of negotiations, while the country’s various governments have all recognised the existence of the root causes of the conflict and committed to a solution based on dialogue.

• Confidence-building measures: The lengthy bilateral ceasefire contributed to building trust between the insurgency and military and police commanders, including at the personal level. This trust is currently the main guarantor that there will be no relapse into armed confrontation. Furthermore, both parties recognise nternational humanitarian law and international human rights treaties (on the recruitment of child soldiers, the prohibition of the use of anti-personnel mines, etc.)These factors have been fundamental in reducing the levels of confrontation and generating trust between the parties and civil society.

• Strengthening of capacities: Both the government and the MILF are well aware of the problems that emerged during the implementation of the 1996 agreement with

the MNLF. The parties therefore decided early on to strengthen the capacity of the MILF to manage civil institutions: in 2002 they created the Bangsamoro Development Agency and in 2009 the Bangsamoro Leadership and Management Institute, both led by the MILF.

Additional highlights

The main peacebuilding developments in the Philippines emerged during the presidency of Fidel Ramos (1992-98). Ramos was a retired general who had been chief of staff of the armed forces during the Marcos dictatorship as well as during the first democratic government, i.e. of President Corazón Aquino. In 1992 Ramos promoted an ambitious process of national dialogue (Coronel-Ferrer, 2002) for the drawing up of a national peace policy. The result of this consultation was a conceptual framework that identified the structural problems affecting the country and defined “six paths to peace”.

The conceptual framework emphasises negotiations between the government and the insurgency as one of the paths to peace, but states that a peace process must necessarily be wider and more inclusive than mere peace negotiations. This innovative national peace policy has coexisted for years in contrast to (and in conflict with) a classic national security doctrine focused on defeating the internal enemy. In 2003 a crisis in negotiations and the return of violent incidents mobilised civil society to promote an initiative of its own to verify the ceasefire, known as the Bantay Ceasefire.

The network was composed of around 200 voluntary members and, despite the financial constraints it faced, became an essential complement to the formal verification commissions, receiving the appreciation of both parties. An additional element is the outstanding role played by women in the peace process. The Philippines is possibly the country with the best implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) on women, peace and security. Teresita Deles holds the position of presidential adviser for peace, while Miriam Coronel was the first woman to lead a negotiating team that eventually signed a peace agreement. Women have also led the legal advisory teams of both the government and the MILF. Similar to other contexts, women in the Philippines have a wide presence and leadership role in civil society, with Muslim and indigenous women playing a fundamental role (Herbolzheimer, 2013; Conciliation Resources, 2015).

Implementation challenges

In spite of the positive developments, the implementation of the peace agreement is facing multiple obstacles. The first limiting factor is time. During the negotiation of the Framework Agreement (2012) the government man - aged to link the transitional period to the end of the presidential term in May 2016. But the negotiating teams have not been able to keep up the agreed pace of negotiation and implementation. As a result, the parties will have to agree to an extension of the implementation period. Responsibility for the delay is shared. On the one hand, the insurgency lacks enough qualified and reliable/trustworthy personnel to take on all the responsibilities derived from the transition.

On the other hand, the government negotiating team has to deal with limited buy-in on both the agreement and its implementation by other sectors of the bureaucracy. At the same time Congress has been dragging its feet in enacting the peace agreements into law, while the judiciary must still assess whether the agreements comply with the constitution. There is a high risk that these two state institutions will raise issues that may further block the implementation of the agreements that have been signed.

Furthermore, in the Philippines, prejudice against Muslims – a heritage from the colonial period – still runs deep. With less than a year remaining until the country’s presidential and legislative elections (May 2016), some prominent politicians and media outlets are turning to populist rhetoric to antagonise public opinion against the peace process. Even among better-intentioned political actors, a lack of knowledge about the social, political, and cultural reality of the insurgency in particular and the Muslim population in general results in faulty diagnoses and mistaken responses.

Successive governments have associated the Moro problem with poverty and economic marginalisation, thus neglecting the relevance of identity and parity of esteem. On its part, the insurgency has been unable to articulate a political discourse that the whole country can understand and endorse. Only after patient dialogue have the peace negotiators deconstructed some of these erroneous imaginaries, but both the Christian and Muslim sectors of society still distrust each other.

The main security-related problem is the proliferation of arms and armed groups. One reason is that holding weapons is legal in the Philippines. Related to this, successive governments have failed in their attempts to disband paramilitary groups run by local politicians. There is also a proliferation of additional armed groups, which can be classified into three categories: an MILF breakaway group that is sceptical about the government’s political commitment (the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters); extremist cells linked to international extremist violence (Abu Sayyaf, Jemaa Islamiyah); and ordinary criminal organisations. Other difficulties are inherent to any process of transition from war to peace. Apart from political will, the government needs to prove its capacity to transform words into deeds, which has historically proved to be a challenge. In parallel, the insurgency needs a radical paradigm shift from a semi-clandestine military structure to a social and political movement – a terrain in which it has limited experience and where to some extent it is at a disadvan - tage compared to more established political actors.

Lessons learned for other peace processes

Each peace process responds to a specific conflict that emerges for concrete reasons and in concrete circumstances (social, political, cultural and temporal). However, comparative analysis is fundamental in every peace process. Some of the lessons from the Philippines could be relevant to other contexts: